Offshore Scotland was a success; so where to next? Founder David Stott’s ambition was to grow the show; but how? More tents at Aberdeen University in March were not the way forward.

However, NESDA (North East Scotland Development Agency) came to the rescue by suggesting the Grampian Regional Council showground at Bridge of Don.

After all, as Stott recounts, it boasted a golf range, a farmhouse and a large amount of open space.

But there was another issue . . . the name of the show. Oil and gas is an international game; the Offshore Scotland brand was parochial and needed changing. On the other hand, something like Offshore Europe had a certain international ring and appeal.

“So we renamed the show Offshore Europe, moved to a September date in 1975, and as the North Sea developments came thick and fast the orders poured in,” said Stott in his original March 2013 article in Energy.

“The infrastructure was entirely inadequate for the scale of show that was taking shape, but in our naive optimism we underestimated the difficulties.

“We erected a vast tented village – nicknamed ‘Tentie Toon’ locally – to house some 800 exhibiting companies from all over the world, and awaited an onrush of visitors.

“On September 16, the opening day of the show, Aberdeen became a grid-locked city. Nothing moved on the roads, as the oil world and some rubberneckers – 36,000 in total over the week – arrived from all points in a rush to reach the Bridge of Don.”

Stott confesses that the exhibition wasn’t ready and the aisles were full of rubbish.

As each day went by, the show staggered from crisis to crisis, culminating in a torrential all-night downpour that nearly took the roof off some of the tents, and making such car parks as we had uninhabitable.”

That was the first time that the weather hit Offshore Europe; but it wasn’t the last. As for the other crises, including a chronic lack of beds, fortunately these were pioneering days, attitudes were perhaps a little more forgiving then than now. After all, out in the North Sea a boom was getting into full swing; witness some key events during 1973 through 75.

Occidental started the roll call of successes for 1993 by declaring its Piper discovery in January.

The company, in consortium with Thomson (formerly an owner of the P&J), Getty and Allied Chemical, had less than a year earlier on March 15, 1972 been awarded a UK licence to explore.

Phillips located Maureen, Total found Ellon and Dunbar, Conoco – Viking D, Shell added Dunlin and South West Dunlin, Britoil – Thistle, DNO – Heather, ARCO – Thames and Kerr McGee – Hutton.

This was great for Aberdeen as most of these finds had been made in the Northern North Sea. Prosperity was by now guaranteed; the city’s decline had been well and truly reversed; as had house prices, which started rocketing from 1973-on.

Mid-‘73 saw local trawler fleet owner and fish processor, the John Wood Group announce mid-year that it was to invest £1.5million in a major expansion programme aimed at capturing North Sea business.

Wood was the first of what turned out to be relatively few Aberdeen families to truly grasp the oil and gas opportunity and to catapult themselves into the international league.

Otherwise, the lion’s share of activity would be and was indeed snapped up by American companies setting up shop in some number. The industry was then as it remains today, foreign-dominated and largely US controlled.

While Peterhead and Dundee began to benefit, one of the hottest spots outwith Aberdeen was surely Highlands Fabricators at Nigg, where the 19,800 tonnes, Forties Charlie, or Highland One as it was otherwise known, was built and completed in 1974. It was the first ever large North Sea jacket built and was quickly followed by others. Hi-Fab was arguably the most successful of the super-yards established for offshore construction. Ardersier perhaps ranks second.

In Shetland, where there was a war of words between local politicians and oil companies going on about multiple oil receiving terminals, locals were exploiting other opportunities.

At North Ness, Lerwick, drilling mud silos had been established, Hudson Offshore was building a base at Sandwick, Bovis was constructing another at Greenhead for Norscot, and P&O was planning a £2.25million supply base on 13 acres leased from Lerwick Harbour Trust.

In the event, Shetland Islands Council won the war of words with Big Oil and Sullom Voe, a former wartime base, was selected as THE oil handling terminal.

Shell quickly announced that Brent oil would be brought ashore at Sullom Voe to a £20million terminal . . . then a huge sum of money in Shetland eyes. In fact, Sullom Voe was eventually to swallow more than £1.3billion!

1973 morphed into ’74 with yet more finds made. Shell declared Osprey in February, Chevron divulged Ninian in April. June saw Claymore (Occidental), Andrew (Britoil now BP) and Magnus (BP) added to the tally. North Cormorant (Shell), Nevis (Mobil) and Galley (Texaco) were others.

And, in the Irish Sea, the South Morecambe gas field was located, so demonstrating that viable hydrocarbon resources could be found elsewhere in UK waters.

On a geo-political note, the North Sea was seen as the one big opportunity there was to get back at Middle East and North African producers who continued to apply pressure.

A measure of the province’s strategic value is that, in 1974, US companies had bagged almost 37% of discovered reserves, while UK companies had just over 41% and the French held 11%.

BP was galloping ahead with Forties with the ambition of achieving first oil in 1975, which it did though many months later than intended.

As Big Oil stormed ahead in the North Sea, it was all change at the polls onshore, with Heath being ousted by Harold Wilson. Heath’s nemesis was the mining community.

Like so many other workers in Britain, the miners were upset about imposed wage limits. They weren’t stupid and played the oil card.

Because the oil price shock generated by the Yom Kippur War of 1973 had impacted on and raised the prices of other energy sources, coal miners felt they were in a position to take a strong stand against the Government in wage negotiations.

Heath wanted to increase overtime work in order to build a stockpile of coal with which the government could wait out an eventual strike by the miners. But his ploy was seen through and the miners simply refused to put in overtime.

The three-day week was introduced to conserve energy and, apparently, build coal reserves. So the miners struck.

Heath had no choice but to go to the electorate and let them vote on the proposition “Who rules – unions or Parliament?” He lost.

Wilson shrewdly appointed former peer Anthony Wedgewood Benn as Britain’s first Energy Secretary in 1975. And first commercial oil flowed, with the Argyll field (Hamilton Brothers) beating mighty BP’s Forties development into the record book. Argyll was brought onstream in June 1975; Forties started up in September.

What a platform on which to make a success out of the 1975 Offshore Europe, even if it was a bit of a shambles!

So where next for Offshore Europe as Stott battled to anchor it solidly in a small seaport so far away from just about anywhere and better known for fish than anything else?

Stott: “Somehow, the (1975) exhibitors did a lot of business, and we survived despite a withering public dressing down from Sandy Mutch, then convener of Grampian Regional Council, which I remember to this day.

“Clearly, lessons had to be learned, and we made a good fresh start by appointing Bryan Weavers as our technical director, Jo Kearns as exhibition manager, and Judith Patten (see her reminiscences on page 9), taking on the all-important public relations role.

“We invested £120,000 of our own money in the site – it seemed a fortune at the time – laying down a hardy Bitmac surface covering much acreage to include proper car parking as well as exhibition space, and rented a brand new and greatly superior type of temporary structure from Aberglen, then Jimmy Milne’s company.

“The 1977 and 1979 shows were both successful and we were becoming well established in the oil exhibition calendar, but it became obvious that as a major international event the infrastructure of OE left a lot to be desired.”

Again, it was the boom that was both carrying and forgiving Offshore Europe as it battled to get roots firmly set down.

If the show was a bit of a bronco, consider the North Sea, presided over by an energy secretary who was out to change things in a very big way.

Crucially, Benn established the British National Oil Corporation; its purpose was to enable the State to take shares in licences and to trade in oil on behalf of Government, which already owned half of BP.

Unlike the oil companies, BNOC would be exempt from Petroleum Revenue Tax. Its participation in licences already awarded would be a voluntary decision for the companies involved. But, in future rounds, BNOC would have the right to take up to 51%.

The organisation formally came into being on New Year’s Day, 1976, after the Wilson era closed. It did not last long. Tory leader Margaret Thatcher saw to its destruction when she swept to power in 1979 as Britain’s first female PM.

Benn’s other big ambition was for the UK to become a member of OPEC (Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries), alongside the likes of Saudi Arabia, Iraq, Iran and Kuwait. That never happened.

The Queen honoured BP and the North-east of Scotland by initiating the flow of oil from the North Sea giant Forties to the refinery complex at Grangemouth on the Forth. The date was November 3, 1975. The location was BP’s Dyce complex.

What she said then was very far sighted in that she talked about what we now call technology transfer.

“What has been achieved in the North Sea can be done on other Continental shelves and, no doubt, seen in very much deeper seas,” Her Majesty said.

“I am sure that British experience and expertise gained off our coasts will have a key role to play in developing this new offshore industry, wherever oil and gas are found.”

Prophetic words, as the hunt for oil and gas has indeed been successfully taken deepwater, almost worldwide . . . the UK Atlantic Frontier, West Africa, East Africa, Brazil, deepwater Gulf of Mexico and Falklands are prime examples.

And that hard-won expertise is indeed being transmitted overseas, and very much to UK . . . and especially Aberdeen’s, benefit.

Back to the North Sea, where hopes had been high that Mobil’s flagship Beryl field would also come onstream during 1975 but delays were to force the first oil date back to mid-1976.

At the time, five huge concrete “Condeep” platform structures were on order for UK projects with their combined capital cost then being quoted at more than £240million (would be £billions today).

1975 was the best year yet on the exploration hunt, with Texaco coming in with Tartan, Conoco/Statoil with the huge UK/Norwegian Statfjord discovery, Amoco – North West Hutton, Shell – Tern, Agip – Balmoral, Conoco – Britannia, Total – Alwyn North, Shell – Fulmar, Marathon – West Brae, plus others.

During the late 1970s, the biggest challenge facing Aberdeen and other upcoming oil and gas centres in Scotland (or wider UK) was the lack of infrastructure.

At that time, Aberdeen District Council (part of Grampian Region) saw the provision of land for industry as one of its most important roles, with a large number of sites provided at East and West Tullos, Northfield, Altens and Mastrick (Whitemyres Industrial Estate).

The district council was also actively involved in development and regulation of the city’s fast growing airport at Dyce.

In 1975, the airport was taken over by the British Airports Authority and a £10million major expansion programme launched, including construction of a new main terminal which was completed two years later on the wrong side for anyone hoping to arrive by train.

On the wider Scottish versus the rest of Britain front – that is the Scottish National Party – the situation in 1976 can perhaps be best summed up by what happened at a press conference in Washington DC.

There, in October, Foreign Secretary of the day, Anthony Crossland, was asked why London was against giving Scotland independence and was reported as murmuring: “Because they have a lot of oil.”

That oil card is, of course, the ace in the SNP’s hand today, just one year off the referendum vote for independence.

The biggest event of 1976 was first commercial oil from Shell’s £2.4billion Brent field development, just five years after the giant’s discovery.

Indeed, by the end of 1976, seven UK North Sea oilfields had been brought onstream – Argyll, Auk, Forties, Montrose, Beryl, Piper and, the most recent, Brent.

And more new finds had been made, numbered among which were Pierce (Ranger), Audrey (Phillips), North Morecambe (British Gas), Machar (BP) Highlander (Texaco), Eider (Shell) and Beatrice (BP) were some. Already, though it was not realised at the time, most of the biggest fields had been located by the end of 1976.

With North Sea benchmark Brent crude up around $30 per barrel, 1977 had the makings of a decent year for the UK. As for Aberdeen, the city was climbing the league table of oil and gas centres rather nicely.

Indeed, at the 1977 Offshore Europe, Lord Provost William Fraser proclaimed that the city had become Europe’s oil capital.

NESDA and the local councils under the Grampian banner, had been working to create the infrastructure needed. Office accommodation and industrial estate developments were filling up rapidly and, in 1977 alone, a dozen new office buildings were completed, with NESDA fielding enquiries for a further 200,000sq.ft.

To help put a scale on the boom that was by now gripping Aberdeen, filling its bars, hotels and bed and breakfasts to capacity, some 500 companies had arrived in the city over the period 1970-77.

Meantime, 1977 saw Total bring the Frigg gas field onstream and Occidental complete Claymore. And, the 600,000-tonne concrete gravity base of Chevron’s Ninian Central platform was successfully floated out of its construction dock at Kishorn in Wester Ross.

On the notables exploration front, BP made the first West of Shetland . . . Clair; Texaco located Captain; Shell found Gannet A and Fina identified Otter.

Stott had a lot to think about after the 1977 show. Even though 1979 looked like becoming a success too, he already faced serious competition when the Society of Petroleum Engineers (SPE), organisers of the OTC in Houston, and in co-operation with the Montgomery Group, launched a major rival in 1978 in Earl’s Court, London, repeating in 1980.

With the new Scottish Exhibition Centre (SEC) in Glasgow in the final planning stages, there was a political desire either to attract OE to Glasgow, or to set up a new oil show in the modern halls, with full conference facilities and all the trimmings in Aberdeen.

Grampian Region had tried to get a pot of money together to fund a permanent facility at Bridge of Don, but failed.

“We were looking decidedly shaky without major improvements, so, under fire from all sides, we swallowed hard and set about trying to raise the finance to build a centre ourselves,” wrote Stott.

“We appointed architects, drew up a plan and after a lot of pressure we finally met our target, the investment being provided by the Royal Bank, the GRC, ourselves and – grudgingly – from the Scottish Development Agency, which was, of course, a firm backer of the SEC.”

And so the Aberdeen Exhibition and Conference Centre came about; with completion just in time for the 1985 show, which was opened by PM Thatcher.

“At last, we could hold our head up high and know that we could compete with anybody.”

As it turns out, Stott has been proved right. It was a miracle, however, that the AECC was ready for the 1985 Offshore Europe as the show also marked the end of the North Sea boom.

It happens that, earlier that year, last rights were administered over the Benn creation BNOC, which Thatcher had sworn she would kill . . . and did.

It happens too that UK output reached a record 127million tonnes of crude, a performance that was to be sustained through 1986 before decline set in.

But OPEC was in disarray; traditional swing producer Saudi Arabia could not maintain discipline among the cartel’s members. The stage was set for a price crunch; anathema to the North Sea.

Following a series of botched moves over price controls, OPEC basically lit the fuse that blew oil markets apart and resulted in the crash of ’86.

Oil, previously fetching $30-plus, plummeted and the spot price dipped to less than $9 during the summer of ’76.

Estimates vary as to the real North Sea impact, but the generally accepted figures are that 6,000 out of more than 28,000 offshore jobs evaporated, plus vastly more onshore.

Oil companies battened down the hatches and collectively slashed exploration budgets by around 30% to not much over £1billion; and capital spending was curtailed £500,000 to £2.3billion.

The impact on Aberdeen and other major centres like Houston was horrific, as it was on Offshore Europe and other major oil shows for years to come. But the cities and the shows survived; as they did the late 1990s crash.

Aberdeen is today riding a wave of prosperity, fuelled in part by the North Sea projects “Indian Summer”. And Offshore Europe 2013 is on track to set new records. Not bad for 40 really.

Offshore Scotland was a success; so where to next? Founder David Stott’s ambition was to grow the show; but how? More tents at Aberdeen University in March were not the way forward.

However, NESDA (North East Scotland Development Agency) came to the rescue by suggesting the Grampian Regional Council showground at Bridge of Don.

After all, as Stott recounts, it boasted a golf range, a farmhouse and a large amount of open space.

But there was another issue . . . the name of the show. Oil and gas is an international game; the Offshore Scotland brand was parochial and needed changing. On the other hand, something like Offshore Europe had a certain international ring and appeal.

“So we renamed the show Offshore Europe, moved to a September date in 1975, and as the North Sea developments came thick and fast the orders poured in,” said Stott in his original March 2013 article in Energy.

“The infrastructure was entirely inadequate for the scale of show that was taking shape, but in our naive optimism we underestimated the difficulties.

“We erected a vast tented village – nicknamed ‘Tentie toon’ locally – to house some 800 exhibiting companies from all over the world, and awaited an onrush of visitors.

“On September 16, the opening day of the Show, Aberdeen became a gridlocked city. Nothing moved on the roads, as the oil world and some rubberneckers – 36,000 in total over the week – arrived from all points in a rush to reach the Bridge of Don.”

Stott confesses that the exhibition wasn’t ready and the aisles were full of rubbish.

As each day went by, the show staggered from crisis to crisis, culminating in a torrential all-night downpour that nearly took the roof off some of the tents, and making such car parks as we had uninhabitable.”

That was the first time that the weather hit Offshore Europe; but it wasn’t the last. As for the other crises, including a chronic lack of beds, fortunately these were pioneering days, attitudes were perhaps a little more forgiving then than now. After all, out in the North Sea a boom was getting into full swing; witness some key events during 1973 through 75.

Occidental started the roll call of successes for 1993 by declaring its Piper discovery in January.

The company, in consortium with Thomson (formerly an owner of the P&J), Getty and Allied Chemical, had less than a year earlier on March 15, 1972 been awarded a UK licence to explore.

Phillips located Maureen, Total found Ellon and Dunbar, Conoco – Viking D, Shell added Dunlin and South West Dunlin, Britoil – Thistle, DNO – Heather, Arco – Thames and Kerr McGee Hutton.

This was great for Aberdeen as most of these finds had been made in the Northern North Sea. Prosperity was by now guaranteed; the city’s decline had been well and truly reversed; as had house prices, which started rocketing from 1973-on.

Mid-‘73 saw local trawler fleet owner and fish processor, the John Wood Group announce mid-year that it was to invest £1.5million in a major expansion programme aimed at capturing North Sea business.

Wood was the first of what turned out to be relatively few Aberdeen families to truly grasp the oil and gas opportunity and to catapult themselves into the international league.

Otherwise, the lion’s share of activity would be and was indeed snapped up by American companies setting up shop in some number. The industry was then as it remains today, foreign-dominated and largely US controlled.

While Peterhead and Dundee began to benefit, one of the hottest spots outwith Aberdeen was surely Highlands Fabricators at Nigg, where the 19,800 tonnes, Forties Charlie, or Highland One as it was affectionately known, was built and completed in 1974. It was the first ever large North Sea jacket built and was quickly followed by others. Hi-Fab was arguably the most successful of the super-yards established for offshore construction. Ardersier perhaps ranks second.

In Shetland, where there was a war of words between local politicians and oil companies going on about multiple oil receiving terminals, locals were exploiting other opportunities.

At North Ness, Lerwick, drilling mud silos had been established, Hudson Offshore was building a base at Sandwick, Bovis was constructing another at Greenhead for Norscot, and P&O was planning a £2.25million supply base on 13 acres leased from Lerwick Harbour Trust.

In the event, Shetland Islands Council won the war of words with Big Oil and Sullom Voe, a former wartime base, was selected as THE oil handling terminal.

Shell quickly announced that Brent oil would be brought ashore at Sullom Voe to a £20million terminal . . . then a huge sum of money in Shetland eyes. In fact, Sullom Voe was eventually to swallow more than £1.3billion!

1973 morphed into ’74 with yet more finds made. Shell declared Osprey in February, Chevron divulged Ninian in April. June saw Claymore (Oxy – now Elf), Andrew (Britoil now BP) and Magnus (BP) added to the tally. North Cormorant (Shell), Nevis (Mobil) and Galley (Texaco) were others.

And, in the Irish Sea, the South Morecambe gas field was located, so demonstrating that viable hydrocarbon resources could be found elsewhere in UK waters.

On a geo-political note, the North Sea was seen as the one big opportunity there was to get back at Middle East and North African producers who continued to apply pressure.

A measure of the province’s strategic value is that, in 1974, US companies had bagged almost 37% of discovered reserves, while UK companies had just over 41% and the French held 11%.

BP was galloping ahead with Forties with the ambition of achieving first oil in 1975, which it did though many months later than intended.

As Big Oil stormed ahead in the North Sea, it was all change at the polls onshore, with Heath being ousted by Harold Wilson. Heath’s nemesis was the mining community.

Like so many other workers in Britain, the miners were upset about imposed wage limits. They weren’t stupid and played the oil card.

Because the oil price shock generated by the Yom Kippur War of 1973 had impacted on and raised the prices of other energy sources, coal miners felt they were in a position to take a strong stand against the Government in wage negotiations.

Heath wanted to increase overtime work in order to build a stockpile of coal with which the government could wait out an eventual strike by the miners. But his ploy was seen through and the miners simply refused to put in overtime.

The three-day week was introduced to conserve energy and, apparently, build coal reserves. So the miners struck.

Heath had no choice but to go to the electorate and let them vote on the proposition “Who rules – unions or Parliament?” He lost.

Wilson shrewdly appointed former peer Anthony Wedgewood Benn as Britain’s first Energy Secretary in 1975. And first commercial oil flowed, with the Argyll field (Hamilton Brothers) beating mighty BP’s Forties development into the record book. Argyll was brought onstream in June 1975; Forties started up in September.

What a platform on which to make a success out of the 1975 Offshore Europe, even if it was a bit of a shambles!

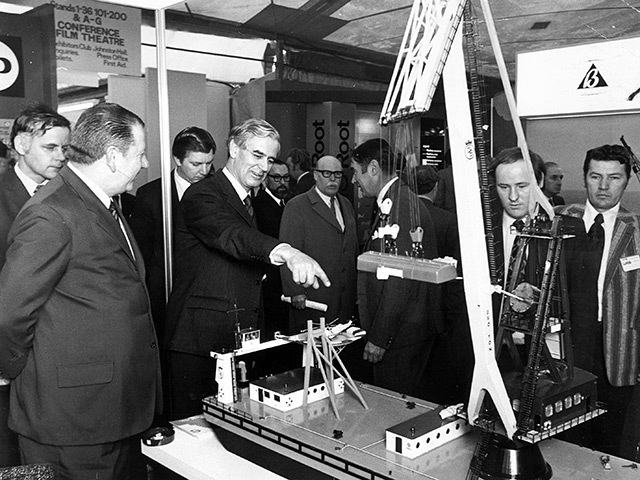

To view and buy a wide selection of images from the last 40 years of Offshore Europe, visit PhotoshopScotland or call 01224 343332

Recommended for you