The threat of a no-deal Brexit is back — and with it the risk that the U.K. economy’s shaky recovery from the coronavirus pandemic will be hobbled.

As British and European Union negotiators head into the last round of talks scheduled before a key summit this month, chances are growing that the U.K. will end the post-Brexit transition period on Dec. 31 without a free trade agreement in place — spelling turmoil for businesses.

Instead of postponing its final parting with the bloc because of the coronavirus, the U.K. government has so far ruled out any delay. That may be, critics say, because Brexiters calculate the cost of leaving without a deal will be obscured by the far more extensive damage wreaked by the virus.

To Sanjay Raja, an economist at Deutsche Bank AG, a no-deal Brexit would halve the pace of growth next year to 1.5%. The U.K. in a Changing Europe, a research group, estimates gross domestic product could be crimped by 8% over 10 years as trade barriers and a reduction in productivity hit output.

“It may be less politically costly for the U.K. to do no deal in the midst of a pandemic, but economically I’m not sure about that at all,” said Jonathan Springford, deputy director of the Centre for European Reform. “It might be that they’re able to get away with it — but I don’t think it changes the view that no deal would impose quite sizable economic costs.”

Citigroup Inc. says the size of the shock could even force the Bank of England to take the controversial move of cutting interest rates below zero because fiscal policy and other tools may not be enough.

Companies now have to think of how to prepare for Brexit while dealing with the fallout from coronavirus. Many are shuttered, indebted and struggling to pull through the lockdown.

The additional debt firms are carrying will make adjusting to Brexit more difficult, according to Alan Winters, director of the U.K. Trade Policy Observatory at the University of Sussex.

The re-introduction of trade barriers with the EU and changes to trading relationships with other countries will require a major re-orientation of exports, he wrote late in May. Heavily indebted firms are less likely to invest in developing new export markets.

“It’s a tense conversation at the moment,” said Allie Renison, head of Europe and trade policy at the Institute of Directors. “Companies are struggling with their survival, and there’s not a narrative yet from government saying to prepare, but they are saying the transition is ending.”

While both the U.K. and the EU insist a deal is still their preferred outcome, the deadlocked talks and the limited time left available mean risk no agreement will be reached is rising: analysts at Eurasia Group now put the odds of that outcome at 55%. EU Trade Commissioner Phil Hogan told RTE last month that the U.K. “can effectively blame Covid for everything.”

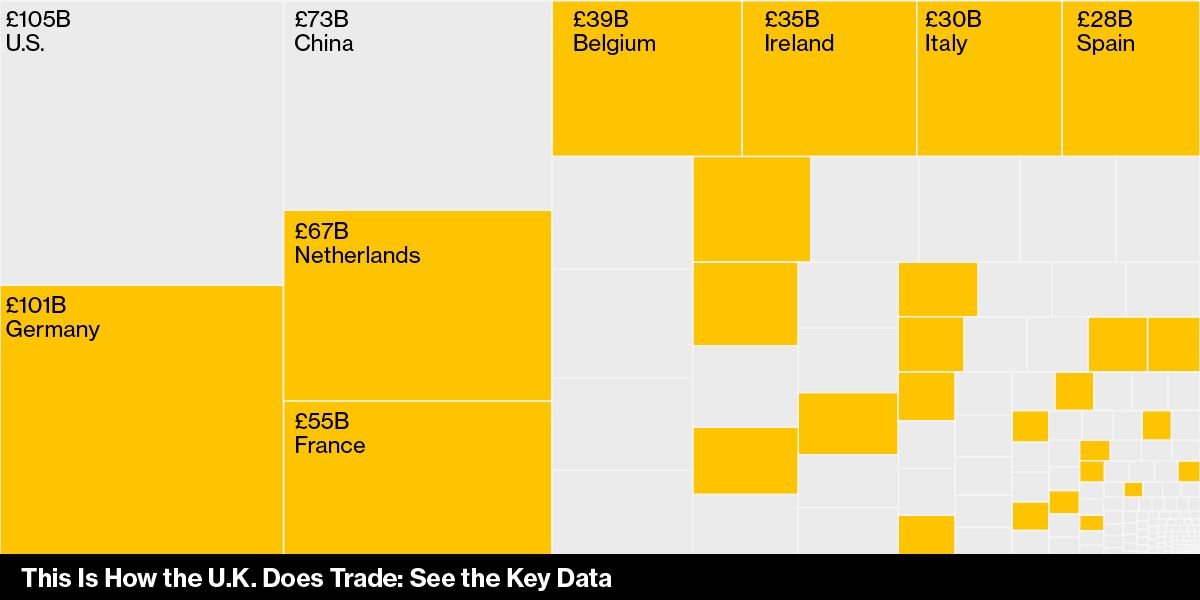

If the sides can’t strike a deal by the year-end, the U.K. will default to trading with the bloc on terms set by the World Trade Organization. That means British manufacturers of goods such as cars, pharmaceuticals, plastics, and precision tools could face new costs and significant disruptions to their just-in-time supply chains in Europe.

For Patrick Minford, chair of the pro-Brexit group Economists for Free Trade, leaving on anything but WTO terms would mean Britain would “lose the gains of free trade with the rest of the world.” It’s also better that the U.K. stays out of the EU’s expensive coronavirus recovery plan, he said. “When you add them both up, it’s pretty serious, really, and we’re much better off leaving.”

The fracturing of supply chains due to the coronavirus is one wake-up call to the upheaval that could be on the way. More than 80% of small and medium-sized manufacturers say the pandemic has affected their supply chains, and while some say contingency plans for Brexit have proved useful in preparing for the situation, others are facing shortages.

The pandemic has also led to discussion of bringing supply chains closer to home, particularly as the U.K. struggled to fly in emergency supplies while factories were closed and most workers stayed away.

U.K. Cabinet Office minister Michael Gove last week touted the “phenomenon of re-shoring” and said “we’re seeing how countries can increase resilience.”

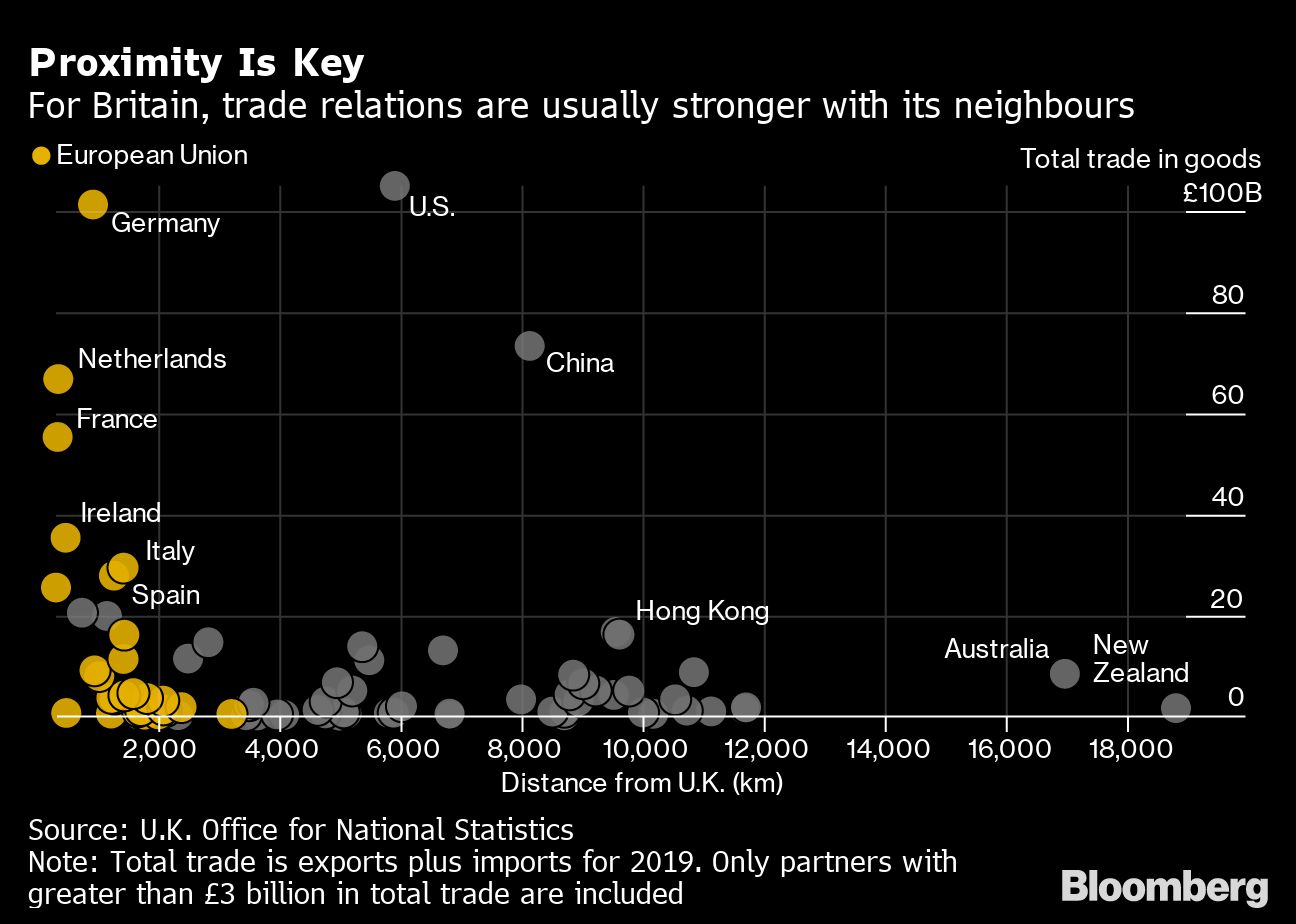

But moves to shorten supply chains further could likely lead to goods becoming more expensive, according to Springford of Centre for European Reform. What is more, the U.K.’s geographical proximity to the EU means it’s likely to stay an important trade partner.

Philip Hammond, a former U.K. finance minister who campaigned to stay in the bloc, said last week that the government should at least seek a temporary trade deal to protect jobs.

Since the U.K. is such an open economy, “we will be more exposed than most developed economies to any headwinds in international trade during the recovery,” he said. “We really can’t afford to layer on top of that, during a very difficult recovery period, a sort of self-inflicted shock.”