The second coming of shale could be even more powerful than the first. OPEC seems to be getting caught unawares.

The current boom in U.S. oil production is even stronger now than the run from July 2011 to April 2015. And this is with oil prices at half their previous level and before President Donald Trump has done anything to meet his pledge to “lift the restrictions on American energy and allow this wealth to pour into our communities.” Output growth could accelerate if prices rise, or costs fall further.

This is not how it was meant to be. OPEC launched a strategy to protect market share in 2014 with a specific aim to knock out high-cost oil production such as shale. After the group succumbed to internal financial pressures and agreed in November to cut output by around 1.2 million barrels a day, Saudi oil minister Khalid Al-Falih said he didn’t expect a big supply response from American shale producers in 2017.

It turns out the response was already well under way, and Al-Falih may not like the numbers. Data from the Department of Energy show U.S. oil production bottomed out in September. Since then oil companies have added an average of 125,000 barrels a day of production each month, taking output back above 9 million barrels a day for the first time since April.

What should really trouble OPEC, though, is that this rate of growth is even faster than the first shale boom. Over that earlier period, U.S. oil production rose at an average monthly rate of 93,000 barrels a day.

Market anticipation of the agreement between OPEC and its friends in November last year, and the actual deal, lifted WTI from a low reached in early 2016 of around $26. This time, shale producers aren’t waiting around — their output started picking up with WTI crude selling for around $45. During the last boom, WTI traded in a range at about double or triple that.

Okay, so part of the growth is coming from the Gulf of Mexico, where BP Plc’s Thunder Horse South and Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s Stones projects have both started producing in recent months. But that region also made a positive contribution to the earlier boom, as did Alaska. Most of the current growth is coming from the onshore, lower 48 states — home of the shale industry.

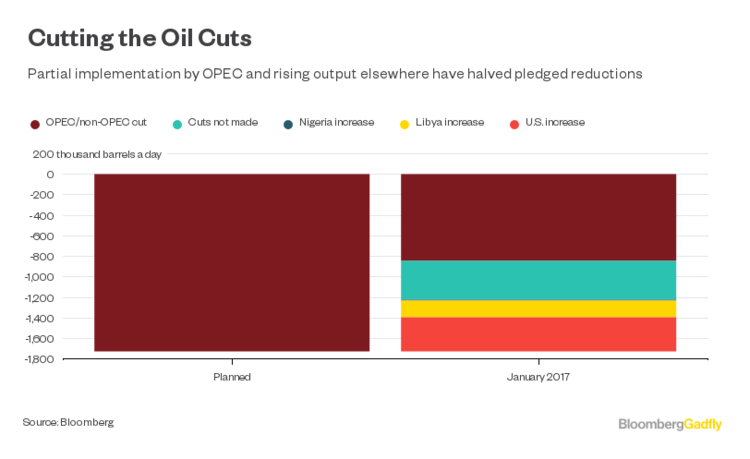

Increasing production from the U.S. is rapidly undermining the output cuts that OPEC is making and, unless those cuts get deeper in the coming months — which looks unlikely, given that compliance is already above 90 percent — things can only get worse for the producer group. Far from bringing the market back into balance, they run the risk that they have seriously underestimated the ability of U.S. domestic producers to adapt to lower prices. And what’s worse is that they may be able to raise production even faster if OPEC succeeds in pushing the price up.

What OPEC has failed to understand is that the shale revolution owes it success more to a new business philosophy to deal with a new type of resource, than it does to new technology. As Thomas Reed, chief executive of JKX Oil & Gas Plc, pointed out at last week’s International Petroleum Week conference in London, horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing have both been in use in the oil industry for around 50 years. What is really new is not just combining the two techniques in a single well but, more importantly, the industrialization of the process of drilling and completing wells.

The long lead-times, complex development plans and huge up-front capital requirements associated with conventional oil fields simply don’t apply in the shale sector. Yes, costs will eventually rise as shale output grows. The industry’s retrenchment has left it employing only the best rigs and crews and focused on the best of the resource. But it is able now to extract so much more with so much less drilling that it is almost certain to keep growing.

OPEC has put itself back on the path of cutting output to support competing producers. It just doesn’t seem to have realized it yet.

Recommended for you