Kenya’s mountains of plastic bags might not seem central to oil’s grand narrative, but they are. Last week, the East African country banned almost everything about them: making them, importing them, selling them, using them, with penalties of up to four years in jail or fines up to $38,000.

More marine plastic than fish by

2050

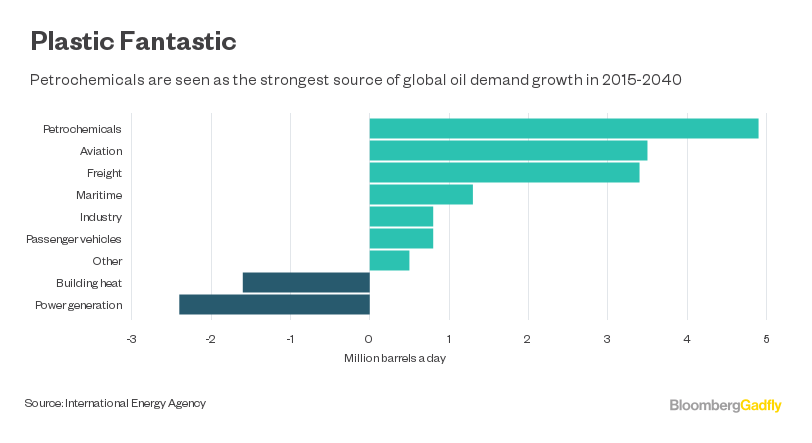

This type of prohibition carries a warning for an oil business that’s depending on petrochemicals — and the plastics made from them — to pick up the slack when we all switch from gas guzzlers to electric cars. Saudi Aramco is betting its future on petrochemicals. The International Energy Agency thinks they’ll drive crude sales for decades, accounting for 44 percent of oil demand growth between 2015 and 2040.

But, as Kenya shows, the days of single-use plastic packaging may already be numbered. And with this stuff making up about a quarter of all the plastic used, that will have a profound impact on the petrochemicals industry.

Environmental fears are only going to worsen. The Great Pacific Garbage Patch — a concentration of marine debris, most of which is plastics — is estimated to be roughly the size of Texas. There are similar areas, brought together by ocean currents, in the Atlantic and Indian Oceans and they aren’t going anywhere.

Plastic doesn’t biodegrade, it just breaks down into smaller and smaller pieces. Remember all those subprime mortgages from a decade ago? They got chopped up and mixed in with “good” debt and sold on as investment-grade securities, almost bringing the financial system to its knees. Think of plastic as a chemical equivalent to those loans: no matter how much it breaks up, it’s still plastic.

On the current track, by 2050 our oceans could contain more plastics than fish (by weight), according to a 2016 report by the World Economic Forum and the Ellen MacArthur Foundation. Plastic waste is moving rapidly up the agendas of countries around the world. Kenya’s ban is one of many initiatives.

Last month, India reaffirmed a ban on non-biodegradable plastic bags in Delhi, while the introduction of a 5 pence charge for single-use bags in England in October 2016 led to an 85 percent reduction in their use. And bags are only a small part of the problem, accounting for 1 percent of plastic waste entering the sea, according to the Green Alliance.

Far worse are plastic bottles, making up one-third of marine plastic pollution. Recycling them would have a huge impact, both on the waste problem and on demand for new petrochemicals feedstock.

Last week, Scotland’s First Minister Nicola Sturgeon committed to introduce a deposit and return scheme on all drinks containers in the country. A similar plan introduced in Germany in 2003 boosted recycling of refillable plastic bottles to 98.5 percent. Several European countries have done the same and more will follow.

All this undermines the petrochemicals sector’s need for oil-based feedstocks from both sides: cutting demand for its end products while boosting the supply of recycled material for the production process.

Just like the electrification of passenger cars, the backlash against plastics — particularly for single-use items such as carrier bags, food containers and bottles — will hurt the oil sector. Yet another existential challenge for Saudi Aramco and others to wrestle with.