It’s happy days for OPEC, but once the whoops and hollers die down, the group should take a long hard look at itself. Because it’s lost its crown as the world’s top oil player.

Shale billionaire Harold Hamm told Bloomberg TV on Friday that forecasts of U.S. oil production growth are way too optimistic and are distorting global crude prices. That news was greeted with big smiles — if not wild cheering — by oil ministers meeting in Vienna to discuss the effectiveness of their output deal. But it is too early for them to start celebrating just yet.

That wasn’t the only boost ministers got ahead of their latest gathering. Analysts at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. said in a Sept. 21 note that the level of Brent backwardation — the premium for crude for delivery next month over that for delivery a year in the future — “is consistent with OECD inventories in days of demand cover falling to 5 percent above their five-year average level.” In other words, OPEC is very close to reaching its target for stockpiles, at least in the developed nations.

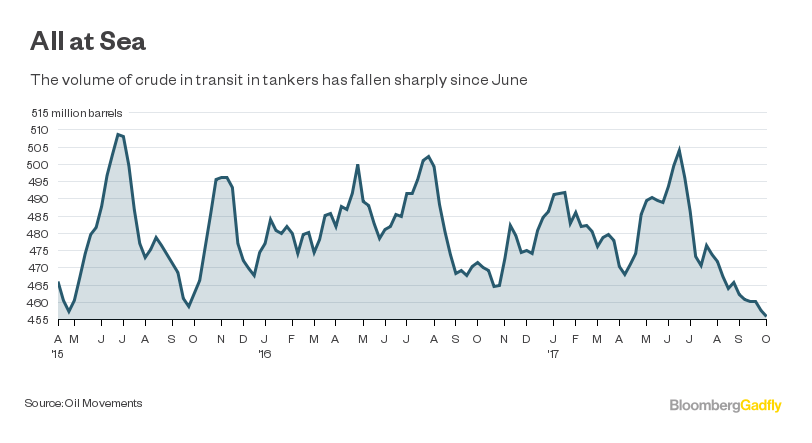

Add to that the latest figures from U.K.-based Oil Movements that show the volume of crude oil in transit on tankers falling to the lowest in records going back to April 2015, along with the growing sense that physical crude markets are tightening.

And there you have it. The group’s cuts are doing the job intended, shale isn’t responding, and OPEC and friends may finally be reaping the rewards from nine months of impressive compliance with the output deals they agreed late last year.

How did U.S. government forecasters get it so wrong? They failed to recognize that U.S. shale producers were finally starting to focus on return on investment, rather than growth at any cost, Hamm said. When oil prices fell with the recovery in Nigerian and Libyan production during the second quarter, shale operators cut capital expenditure and output started to fall.

The result is that, while official Department of Energy forecasts as recently as last month showed U.S. crude production reaching 9.82 million barrels a day by December 2017, the Domestic Energy Producers Alliance — a group representing domestic onshore oil and natural gas exploration and production, chaired by Hamm — sees it at 9.35 million.

Once the market recognizes the U.S. forecasting error, Hamm said, crude prices could rise to $60 a barrel from around $50 now. Good news for OPEC then. The group is targeting “a figure close to $60 a barrel,” Nigerian Minister of State for Petroleum Emmanuel Ibe Kachikwu told Bloomberg TV in Vienna on Friday.

But there is a sting in the tail.

Hamm, CEO of Continental Resources, the biggest leaseholder and producer in the Bakken oil basin, said he didn’t believe that now was the right time to start hedging next year’s production. Not everyone agrees. Oil producers have been stepping up hedging activity as 2018 WTI prices rose above $50 a barrel, according to analysts from Citigroup Inc. and BNP Paribas SA. That hedging will help lock in revenue and underpin growth in shale production next year, even if oil prices slip again.

So OPEC still faces the same problem that it has since oil started to weaken in 2014. It appears that the price level they are seeking to achieve simply stimulates growth in rival supply. Looked at from another direction, there’s a more important question: Has U.S. shale usurped OPEC as the global swing producer?

Hamm’s observations about the rapid response of U.S. producers to price weakness in the second quarter suggest it has. The next test will come if oil prices continue their rebound seen over the third quarter. If shale producers respond with increased investment and stronger output growth, it will be a clear indication that it is their price needs, not those of OPEC countries, that will determine some sort of equilibrium around which oil prices will fluctuate.

But perhaps a study published earlier in the week by analysts at Wood Mackenzie is what OPEC really wants to hear — without technological innovation to overcome dwindling reservoir pressure, production from the Permian Basin could peak as soon as 2021. The shale boom flash in the pan will flare out and the world will return to “normal,” with incremental demand to be met from the core OPEC countries and Russia once more. If the 158-year history of the oil industry has taught us anything, though, it is surely that innovation is one thing it is very good at.

Recommended for you