The drama around President Donald Trump and Iran’s compliance with the nuclear deal has grabbed the oil world’s attention. This gaze should shift west. Rising tensions in northern Iraq could have a much more immediate impact on oil flows that could lead prices higher, and squeeze producers and refiners.

The collapse of so-called Islamic State in Iraq ought to be a cause for celebration and national renewal. Instead, it has dragged the country to the brink of a civil war that, on top of the unnecessary human suffering, could cause the loss of more than half a million barrels a day of exports.

The ousting of insurgents from their last strongholds in northern Iraq has brought the Iraqi military and Iranian-backed militias into direct contact with forces loyal to the Kurdish Regional Government in the oil fields around Kirkuk. Although these produce much less than the fields in the south of the country they are nonetheless important, both economically and strategically, to the Kurdish and Baghdad governments alike.

The Kurds built their own pipeline to the Turkish border after the Baghdad-controlled line fell into the hands of ISIS in 2014. Kurdish troops also took control of areas around the city of Kirkuk, including several oil fields, after the Iraqi army fled. While its actions certainly stopped those fields from falling into the hands of insurgents, Baghdad now wants them back.

As if the situation weren’t tense enough, the KRG has just held a referendum on independence. The polling wasn’t confined to the Kurdish governorates of northeast Iraq, but included the disputed Kirkuk region as well. The result was overwhelming, with more than 92 percent voting in favor of self-determination.

Does this matter to anyone outside the region? You bet.

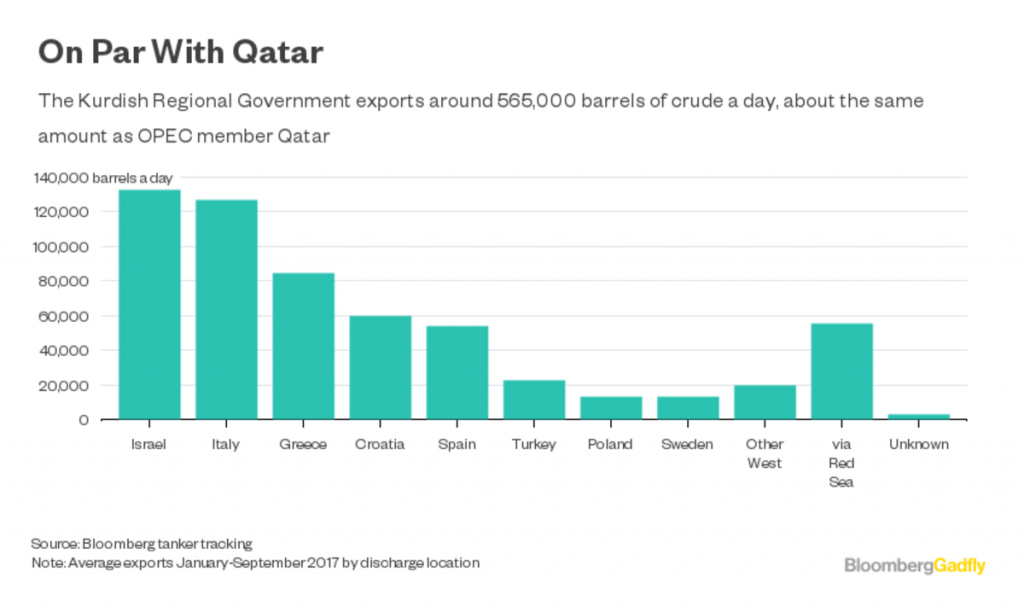

Turkey, fearing the impact of the referendum on its own Kurdish population, has threatened to shut the pipeline from Kurdistan to its Mediterranean oil terminal at Ceyhan. The KRG has exported 160 million barrels through Turkey so far this year, according to Bloomberg tanker tracking. Although the flow has remained undiminished in the three weeks since voting took place, Turkey could stop it overnight.

Around a third of this oil is produced by foreign investors like DNO ASA, Genel Energy Plc and Gulf Keystone Petroleum Ltd. Bigger companies with strong political backing have also invested in the region. Russia’s Gazprom Neft and Rosneft both have interests in Kurdish projects, as does Chevron. Not only could any disruption hurt these companies, European refiners would also get squeezed.

And Baghdad’s own northern output is at risk. After losing its pipeline to Turkey, the Iraqi government has been shipping crude produced by its North Oil Company through the Kurdish infrastructure. However two-faced officials must be about the operation — they denounce oil sales by the KRG as illegal — they’ve got no choice but to use it during the long period it will take to develop an alternative.

Kurdistan is clearly in a very vulnerable position. It is heavily dependent on revenues from oil exports, but those in turn are entirely dependent on transit across Turkey. There is no other viable route to get Kurdish crude to international markets in any meaningful quantity.

But it is not just Turkey’s economic threat that the Kurds are facing. Iran has closed border crossings, Baghdad has banned flights and imposed banking restrictions. Iraqi troops and Iranian-backed Shia militias seem to be gathering on the borders of Kurdish controlled territory. The Kurds have sent 6,000 additional troops to defend Kirkuk, fearing an attack.

None of this need happen, though.

Unlike the independence referendum in Spain’s Catalonia region, the Kurdish poll was non-binding. Its purpose was not to declare independence, but to provide a mandate for Kurdish leaders to negotiate a new relationship with Baghdad. The opportunity created by the defeat of ISIS in Iraq ought to be used as a platform for negotiations around a federal structure for the country that preserves its geographical integrity and oil flows while creating conditions for the inward investment it so desperately needs.

However, it’s uncertain whether the armed and political threats will escalate. If Kurdish exports are halted, the effect will extend far beyond the immediate region. Mediterranean refiners may find it difficult to replace Kurdish barrels quickly, because alternatives will have to travel much further to reach them. That dislocation will almost inevitably tighten Mediterranean crude markets and, if prolonged, can only help hasten the draining of inventories.

While the politicians obsess over Iran, the immediate focus for everyone involved in the oil market should be Iraq.