Newcastle, the Australian port that’s the biggest export harbor for thermal coal, is planning a shift away from the commodity that generates the overwhelming majority of its trade volumes BHP Billiton Ltd., one of the world’s largest coal miners, is considering quitting the industry’s global trade body and perhaps the U.S. Chamber of Commerce because it can’t reconcile its policies on climate change and energy policy with their more coal-friendly stances National Australia Bank Ltd. promised not to lend to new thermal coal projects and ING Groep NV pledged to reduce its exposure to coal generators to close to zero by 2025 China Merchants Bank Co. joined the lengthening line of lenders disavowing advances for Adani Enterprises Ltd.’s Carmichael project, one of the largest such developments worldwide but one that’s highly unlikely to go ahead South Korea, one of the world’s biggest coal importers, announced plans to phase out coal by 2079 and sharply cut its use by 2030 The International Energy Agency said that coal demand would remain essentially flat until 2022 — particularly striking given that in recent years it has tended to overestimate coal’s prospects

You’d think from this newsflow that the main benchmark for globally traded coal would be wilting. In fact, it’s been on a tear.

Next-month Newcastle thermal coal futures bust through $100 a metric ton last week for the first time in more than a year, after rallying 39 percent since the start of June. For all the doom and gloom about the future of the black stuff — including from this Gadfly — the past two years have been a boom time for coal prices that’s only exceeded by their 2010 to 2012 peak.

That’s good news in the short term for coal miners like Peabody Energy Corp. and Glencore Plc, which have enjoyed rising profits from digging up soot. In the long term, though, it’s another nail in coal’s coffin.

Solar module costs since 2011

-80%

When businesses whose costs are rising go into competition with ones whose costs are falling, only a fool would bet on the former group. Yet while Newcastle coal prices are 25 percent below their level at the start of 2011, solar module costs have slumped 80 percent.

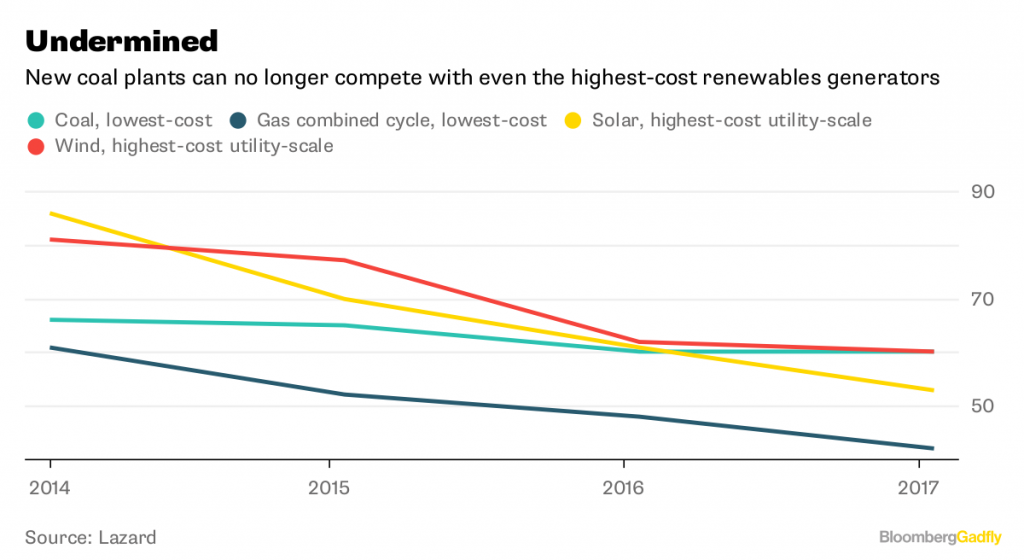

In Lazard’s latest annual analysis of levelized energy costs — essentially, the prices at which new projects will be able to generate electricity — the highest-cost solar and wind projects are now coming in below or equal to the lowest-cost coal generators.

This is unsurprising. Solar modules and wind turbines are manufactured objects, which over time tend to show marked price declines as refinements to repetitive factory processes and supply chains squeeze expenses out of the system. Productivity gains in the mining and engineering industries that are responsible for digging up coal and building generating plants tend to be much slower. Fossil fuels are in a race they can’t win.

That helps explain why banks are becoming increasingly vocal about their unwillingness to lend to coal miners and generators. It’s not just altruism. Their bigger concern is that by backing coal technology, they’ll be making bad investments, much like their forebears who lent money to the pony-and-trap industry, just as the motor car was taking over. Peter Grauer, the chairman of Bloomberg LP, is a senior independent non-executive director at Glencore.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Recommended for you