Are we there yet?

We’ve learned two things on the oil policy of OPEC and friends from meetings in Muscat, Oman and Davos. They don’t know the destination, but they know they haven’t got there.

Since the group started their output cuts in January last year, it gradually emerged that they had a goal of returning inventories to a five-year average level. But this benchmark has never been precisely defined. What inventories? Where? Measured in what units? Against which five-year baseline? None of these questions has yet been addressed.

Saudi oil minister Khalid Al-Falih admitted as much during the press conference after the Joint Ministerial Monitoring Committee meeting in Muscat last weekend, when he suggested that a technical discussion was required on what the oil market needs in terms of inventory. But inventory levels themselves are not a particularly good metric on which to base output policy.

Using them as a goal may dampen some of the political heat that accompanies a price target, but the disadvantage is that they’re a backward-looking measure. We don’t have an accurate picture of what stockpiles are at any given time until several months later. The latest data for OECD inventories, published by the IEA on Jan. 19, are for the end of November, while figures for both September and October were revised by as much as 12 million barrels.

That said, OPEC has become averse to setting a price target, perhaps in part because it wants to avoid accusations of manipulating the oil market. So an inventory target it is. But that raises the question of what inventory target.

It has become common to see the target as returning OECD commercial stockpiles to their rolling five-year average level — but that is largely because OECD stockpiles are the only ones that are widely and consistently reported in an accessible form. As an actual measure of how much oil the world needs to hold in reserve they are pretty useless.

Limiting the focus to the OECD ignores more than half of the world’s oil consumption and not just any old half, but the most dynamic one. Over the past five years, non-OECD oil demand has increased almost five times as fast as consumption among the developed nations, adding 6.4 million barrels a day between 2012 and 2017, compared with just 1.3 million in the OECD countries, according to the International Energy Agency.

The second problem is that measuring inventories in simple volume terms takes no account of the function those inventories perform. Aside from providing opportunities to profit from movements in oil prices, inventories play an important role in matching a seasonally variable oil demand to a much less seasonal profile of supply. They also act as a buffer to provide protection from supply disruptions or spikes in demand. This suggests that stockpiles should be measured in terms of the number of days for which they can perform this role, rather than simply in barrels.

With oil demand increasing on average by close to 1.7 million barrels a day in each of the past three years, the world needs more oil in storage to provide the same buffer. Accounting for stockpiles in days of demand cover, or perhaps days of import cover, which is how the IEA’s emergency stockpile obligations are defined, would be a big improvement over a simple volume accounting.

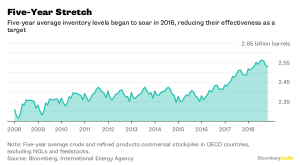

And then, no matter whether you measure in barrels or days, there is the problem of the target OPEC and friends are trying to reach. Why the five-year average level of inventories? Why not four, or six? And, as Al-Falih noted in Muscat last weekend, there is the problem that the five-year average is itself influenced by the very excess stockpile that the group is trying to drain.

I have highlighted this issue before, but recent data from the IEA show just how big that influence is. The five-year average level of OECD crude and refined product stockpiles has risen by about 150 million barrels since mid-2016. Given that the excess OECD inventory was initially pegged at around 340 million barrels, that’s a big difference.

All of these matter. Without knowing where they are trying to get to, OPEC and friends risk missing the turning point when they need to begin relaxing their grip on supply. According to Citigroup, including inventories beyond the OECD’s shows they are already behind the curve.

OPEC’s two big beasts disagree. Khalid Al-Falih and his Russian counterpart, Alexander Novak, concurred that output curbs need to be prolonged and that some form of restraint may still be needed next year.

The output cuts, planned or otherwise, that OPEC and friends have made over the past year have transformed the oil market outlook. Now Al-Falih needs to get his technical discussion underway quickly so that ministers have some real idea of where they should be heading when they meet in June.

Recommended for you