It’s well known among those who keep hens that happy “chooks” lay more eggs.

The effort required is pretty basic – provide good food, decent accommodation and a reasonable amount of space to scratch around in.

And most of us who have a dog realise that the canine member of the family can have a remarkably positive impact on our home life, as long as they are decently treated.

Why is it that too many bosses seem not to know how to get the best out of their employees?

I’ve just been rereading a small but important report published in June 1998 by the UK Offshore Operators Association (UKOOA), which later morphed into Oil and Gas UK.

The report, titled “The Need for Competitiveness and Stability”, is relevant today. But the bosses behind the report and broader North Sea leadership 20 years ago have largely gone.

Though mostly well-schooled and very experienced, I rather think they were not as highly qualified on paper as today’s counterparts, especially mid-rankers and seniors.

I’ll bet anything that a higher percentage of today’s leaders are better coached in people and culture related issues than the guys who bestrode the North Sea back in the CRINE era.

But the current mess surrounding offshore rotas suggests they might as well not have bothered with the schooling.

Recent developments include Shell deciding to revert to two weeks on, three weeks off (2:3), though not until next year.

Total employees accepted a 15% pay rise in exchange for moving to 3:3, bringing them into line with crew on former Maersk Oil installations. Apache will switch its own staff members back to 2:3, but contractors will remain on 3:3.

Repsol Sinopec is conducting a review of its 3:3 schedule, with a decision expected before the end of the year.

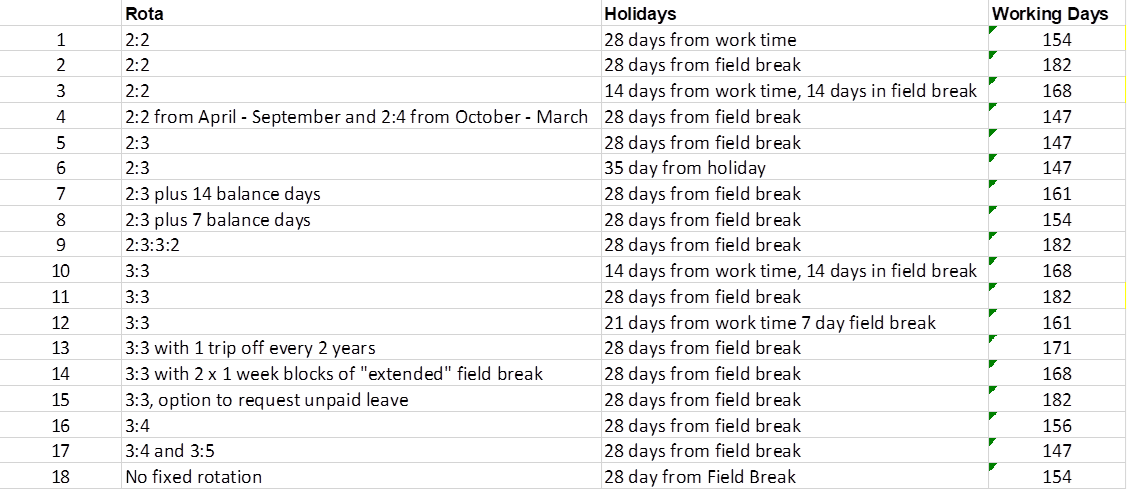

RMT regional organiser Jake Molloy has shared a table of offshore schedules with me. Don’t worry, the companies have been anonymised.

A quick check of the table shows that a fair few companies never did shift to 3:3 during the last oil crisis, sensibly so in my opinion.

If you’ve never been to sea in the winter, as I have in my past, let alone a North Sea installation, which I haven’t, you might begin to understand what I’m driving at.

One of the uglier aspects of people management that has emerged lately is cultivation of what I can only describe as the “us and them” culture – contractors versus company people.

It’s not accidental. It’s deliberate, in my view, and symptomatic of a much wider “bosses versus workers” malaise in the UK.

It is a culture that I naively thought had been left behind following the CRINE revolution of the 1990s. The mantra then was built around that great mafia word “respect”.

It seems that little of past learning has made it through to today’s culture, where some operators practise a differentiated offshore rota that favours company employees.

One of the little-reported effects of drastic offshore cost-cutting over the past five years is that, aboard many UKCS production installations, two-berth cabins have been converted to three-berth cabins to avoid the need for hiring flotels during maintenance and modifications campaigns.

As a result, contractors have been forced to adopt “cabin sharing etiquette”, a piece of terminology that is new to me. Meanwhile, the rule of thumb in Norway remains one person per cabin.

According to RMT, sickness and other absences are on the rise as are mental health problems in what appears to have become a more pressured working environment on the UKCS than ever before. I’m sure there are exceptions out there from which everyone can learn.

Ultimately, something could very well go badly wrong as a result of the current situation offshore UKCS. The MER ambitions for the long-term future of the North Sea will end up being compromised too. There is also the issue of compromised safety.

There is another industry building a presence out there in the North Sea. Offshore wind power is becoming a high profile business in its own right and a significant employer.

It isn’t cyclical like oil and gas. It seems not to hire and fire like oil and gas – at least not yet. It has already sucked in a large number of offshore workers who have become disillusioned with oil companies and contractors.

Most are unlikely ever to return, even if North Sea oil and gas achieves a sustained recovery this time and the industry once again bleats about skills shortages.

Then what? Just think chickens, or cast an eye in the direction of the family mutt.

Recommended for you