Recent press on a skills shortage for the oil and gas industry prompted me to share my views on graduate training and recruitment. It is focused on my own discipline Chemical (Process) Engineering, a key skill for the oil and gas industry.

As someone who has recruited scores of chemical engineers in industry for more than 40 years, and as a university chemical engineering lecturer, I have watched with bewilderment the rise of the graduate assessment centre. These assessment centres are now a feature of the recruitment process where employers bring together a group of candidates who complete a series of exercises, tests and interviews that are designed to evaluate suitability for graduate jobs within their organisation. Of course, graduate recruitment is of prime importance for the longevity of many companies, but are assessment centres really appropriate, or necessary, for recruiting chemical engineers?

Why pass on the responsibility for screening chemical engineers to non-technical individuals? Role playing, psychometric testing, observing group discussions – what does it all provide? Most companies will identify the number of chemical engineering graduates required and where they will begin their career – operational site, design office, R&D, etc. So surely it would make sense for the manager of the recruiting department to identify the new recruit? Obvious key qualities would be technically strong, good team players and good communicators – traits that a competent manager could identify given an hour or so with potential candidates. I would contend that they would do a better job of recruiting than having the same candidates spend two days at an assessment centre. I’d argue that if a manger can’t identify suitable recruits then they should not be a manager.

During my time in industry, my preferred route for recruiting graduates was through summer or industrial placements. That would allow a 2-3 month ‘interview’ by both sides. The experience allows for an almost guaranteed assessment of the suitability of the graduate. I have noted that some companies now use assessment centres to select candidates for summer placements too. This is certainly good business for those running the assessment centres.

And what was wrong with the so-called “milk round”? The employer reviewed CVs and identified students for interview. The employer visited the university during the first term and screened candidates via half-hour sessions. This provided a shortlist of candidates that were then finally interviewed by technical managers during the spring break. The half hour was only a minor intrusion into the students’ study time. Human resources’ only involvement was to discuss terms and conditions. That’s how it used to be. Are chemical engineering graduate numbers now so high that this is no longer possible? I don’t think so.

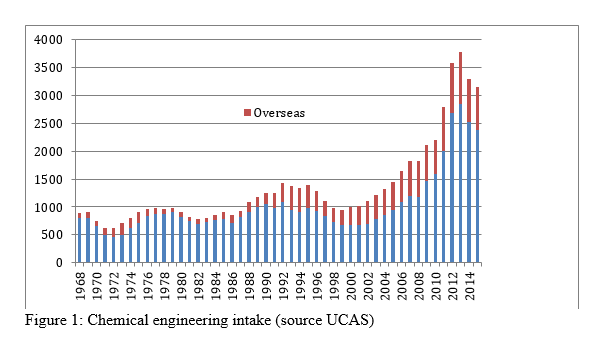

Figure 1: Chemical engineering intake (source UCAS)

As can be seen from Figure 1, the annual UK chemical engineering student intake hovered around 1,000 for around 30 years, which was followed by a very rapid rise. What was the catalyst for the rise? I think it was mostly driven by former prime minister Tony Blair’s 1997 “Education, education, education” initiative. While the importance of education cannot be disputed, I think the mantra should be “The right education, the right education, the right education”.

It is a bit of a head scratcher as to why so many more chemical engineers were being educated when the UK chemicals industry was shrinking. Does “the right education” involve offering more university courses and having more students going to university? Perhaps the right education means more apprentices and more technicians. In my early career days I recall there being a significant number of employees with HNDs in chemical engineering. That seemed to be a perfectly appropriate qualification for many industrial roles. Furthermore, with today’s fee system, the HND route would not leave graduates with large debts after 4–5 years’ worth of study.

I am not convinced that our education priorities reflect the local/national demand with respect to chemical engineers. I am aware of the many reports stating we need more engineers, but I know of no large employer of chemical engineers that is saying “hey you need to train more”.

Returning to assessment centres, what also bugs the hell out of me is that assessments are held during term time. Usually the last term of the most important year of the student’s degree. I have had students requested to attend an assessment centre during exam weeks. I have even had a request that a final exam be rescheduled. How unaware of university practices must an assessment centre be to suggest that? Many students attend 4–5 centres – with travel time that could result in them losing 15 days of final-year attendance. Employers – if you have to conduct these assessments, why not do at the summer, winter or spring breaks?

Speaking about their assessment centre experiences, my students told me:

“When it comes to diversity and inclusion issues you know the answer they want to hear” (The student knows what the interviewer wants as an answer. They give the right reply whether they believe it or not, you can’t do that with a technical question)

“It felt like going back to school, carrying out menial tasks and completing patronising tests (for example, a maths test based on GCSE standard knowledge)’. “There were 3 separate interviews on the day, these were “strength-based interviews” which consist of pre-set questions which are to be answered with no input from the interviewer. Overall, this trip (for which costs were not even covered) felt like a complete waste of time.“

“The levels of hell that must be travelled through to even be in contact with a recruiting engineer are a farce”.

I also sense a high level of stress caused by the assessment centres at a time when the student should be focussing on their studies.

The most telling anecdote I heard was of the graduate who had previously spent a summer placement with a company. Staff in the department agreed that the student was a perfect fit for them. The company assessment centre failed that same student the following year.

Most of the companies using assessment centres insist on a 2.1, or a first-class degree classification. It is interesting to review what has happened to degree bandings. Comparisons of the bandings I have experienced are shown in Table 1.

| Degree classification | 1970s | Present day |

| 3rd class/pass | 50–59% | 40–50% |

| Lower second 2.2 | 60–64% | 50–59% |

| Upper second 2.1 | 65–74% | 60–69% |

| First 1 | 75%+ | 70%+ |

Table 1

The table clearly shows that the bands have been reduced making it easier to obtain a specific grading. Is it any surprise that the media is picking up on the increase in the number of 2.1s and firsts? For many universities the percentage of students gaining a 2.1 or a first is more than 90% the averaging being around 75%. Does that feel right? As a former employer it certainly does not. A first used to be an indicator of an exceptional student, that is no longer the case. Of course there are still exceptional students but they are not clearly differentiated by the modern grading structure.

My experience also indicates that there is a large difference in ability between students averaging in the low 60s and those averaging high 60s. In the past this would have been picked up by the grade band, but this is no longer the case – nowadays, both would receive a 2.1. Similarly, today, students averaging low 70s and those averaging high 70s would both receive a first.

What worries me most, is that the pass mark for UK degrees is now commonly 40%. Are we saying that graduate engineers with real responsibility have potentially failed to grasp 60% of the learning outcomes of their degree? It will come as no surprise that I consider the current grading system to be badly flawed.

There is also a suggestion that exams are getting easier. I’m not so sure but I do feel that we are getting very good at teaching students how to pass exams, and that includes schools. Critical thinking and problem solving – well that’s another matter. I do think that we should be working harder to teach students how to handle the multi-stranded problems that they will face in industry.

Am I just a dinosaur who grumbles “it wasn’t like this in my day”? I don’t think so and with respect to chemical engineering assessment centres, student numbers and degree gradings, I think there is a mammoth in the room.

Recommended for you