While the shift from hydrocarbons to renewables is far from smooth, investment opportunities in the generation, service and utility markets are proliferating as the sector landscape evolves.

As global energy demand continues to grow, driven by increasing electrification, the energy markets face major challenges in balancing the desire for cleaner energy with existing infrastructure and the reality of increased demand.

The energy mix is shifting towards renewables, but by no means overnight. As many people know, the share of oil-generated energy is forecast to fall from 33% in 2020 to 27% by 2040. In the same period, renewables – wind and solar in particular – will combine to meet around 30% of energy demand.

As the renewable share currently stands at 11%, this is a massive shift.

Talking the Talk

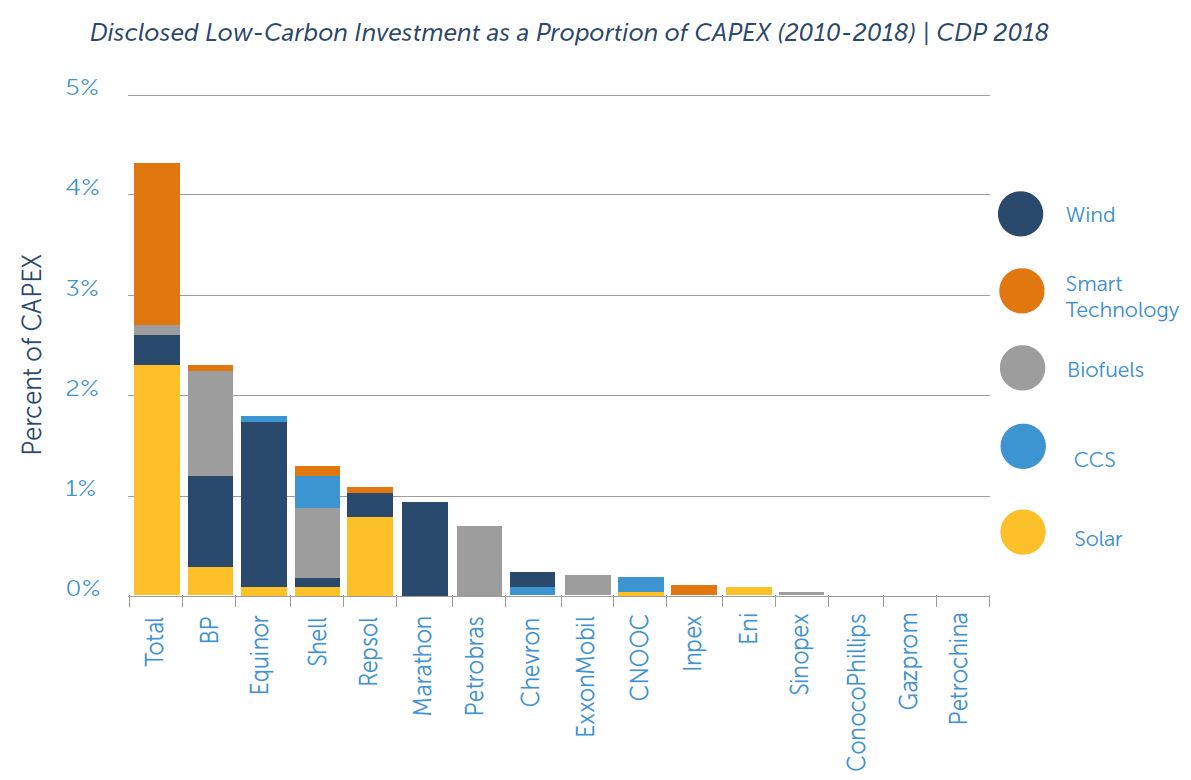

All the major European operators are investing in renewables, but many would question whether they are investing enough.

The key to understanding levels of commitment is to view investments as a proportion of CAPEX rather than stand-alone figures.

For instance, Shell has pledged to invest $1-2 billion per year on ‘new energy’ opportunities, but this is only a small proportion of their CAPEX budget. It will take time for investors to adjust to an environment that does not generally provide high returns.

In 2015, 80% of Total’s CAPEX was spent on upstream oil and gas and 5% on renewables. In 2018 these figures were 82% and 5% respectively. Eldar Saetre, CEO of Equinor, whose stated mission is to increase their spending in the sector from 5% to 15-20% by 2030 recently said “now that we see that the subsidies are more or less fading away, and we are being as an industry met with more emerging risk, we expect the returns to come somewhat up, [as] high risk should also be providing high returns. So, for our investments to be sustainable in the renewable space, when it comes to offshore wind, investment conditions must improve.”

Walking the Walk

Despite such hesitation and uncertainty, there is a sea change underway in the sector. Some operators have shown the way forward with major commitments: Ørsted ASA have successfully transitioned from oil operator to the world’s biggest offshore wind major. 80% of their CAPEX is currently going on developing offshore wind farms.

Some commentators quote the fact that renewables investment peaked in 2017 as evidence of the stalling of renewables, but in fact this is a result of the falling cost required to generate the same amount of energy created by solar and onshore wind. Solar is now cheaper to produce than coal and gas. To produce one megawatt-hour of electricity is now around $50 for solar compared to $102 for coal and $60 for gas.

Although the picture is necessarily very different in developing economies, renewables are racing towards dominance in the developed world.

Between January and May 2019, Britain generated more power from clean energy than from fossil fuels. In 2018, carbon-free sources of electricity, including nuclear and renewables, accounted for almost 50% of total electricity production in the UK.

Only around 3% of UK electricity comes from coal today, a tenth of what it was only ten years ago. In the USA, institutional and big business demand for renewables is beginning to outstrip consumer pressure and is reshaping the market. Entire States want to become renewable-only consumers of energy, and this month Unilever announced that it had moved to using 100% of renewable electricity across five continents. Other global businesses will follow their lead.

Investment Impacts: From Power Storage to Carbon Capture

On the investment side these major shifts are fragmenting the utilities market and creating opportunities in a number of interesting new areas. The rise in impact investing and energy transition funds will also mean that there will be an increasing level of dry powder, looking to invest in this space.

Calash highlights a few opportunities to look out for:

- Secondary Buyouts: The investment from the supermajors by their venture funds and by direct investment in technology, production and distribution focused renewable businesses means that many of these are now reaching maturity and are ready for secondary buyouts.

- Local Specialties: Watch out for specialised generation projects focused on the resources available in a local geography but requiring globally-proven technology, e.g. hydro in Vermont, or solar in Arizona.

- Storage & Stabalisation: Because of the volatile nature of renewable energy supply there is expected to be a rise in grid outages, so we can expect to see increasing investment around storage and utility-specific stabilization technology.

- Mini-Grids: Look for a sharp rise in the number of mini-grids in emerging economies. There needs to be major investment from the private sector to make this happen. According to the World Bank over $200 billion is needed to connect half a billion people to over 200,000 mini grids in Africa and Asia by 2030. These could be supplied by mini-LPG, waste to energy, tidal, mini-hydro as well as solar and wind.

- Conversions: There is potential for the conversion of coal powered stations to gas or other fuels in order to use their existing connection to the grid. This is an area of growth in the USA and Europe will soon follow.

- CCS Projects: At present carbon prices are lower than CCS costs so this is being addressed with prices rises that will make CCS profitable. The Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition recently announced that carbon prices need to be at least $40-80 per tonne by 2020 and $50-100 by 2030. The US currently emits 5bn tonnes of CO2 a year and Europe approximately 4.5bn; at these volumes CCS projects are extremely sensitive to carbon price, but there are a number of new start-up businesses in this sector, supported by large corporate investors.

Conclusion: Adapt & Thrive

The investment environment is changing along with the energy mix. The service sector will be much smaller in renewables due to the shorter supply chain and simpler methods needed to generate power. As a result, investors will need to cover the full breadth of the industry from generation to service and utility markets.

There are plenty of opportunities and more will emerge. The venture funds of the supermajors will be a major source of M&A with their portfolio’s starting to reach maturity for secondary buyouts, as well as co-investment opportunities for first round investments.

There will be growing opportunities in an increasingly fragmented market with more mini-grids and specialist localised power generation.

But old investment models have limited applications. Investors putting money to work in this market may have to reduce their deal size and increase their risk appetite to succeed. Speed is also key. The growing number of startups in the sector have significant opportunities to capitalise on the shifts in supply, but there is such high demand from investors that the players that have reached a position of scale have already been snapped up.

Market structure, sensitivity and dynamics will vary hugely by geography, and this creates major challenges for investors. Oil is not really used for power in the developed world, but it is the main source in the developing world, with diesel generators, no power grids and limited infrastructure.

The emissions issue in 15 years will not be from Europe but from the developing societies – how should an investor plan to adapt in that scenario? The answer may lie in what is perhaps the greatest difference in the energy transition: renewables are not limited by access to a geographically limited and controllable resource like oil.

As a result, we are now moving from an energy system of regional scarcity to one of potential abundance for almost every country around the world. This is because for the first time almost every country will have some degree of energy independence within reach, with an ability to harness some form of renewable energy. They will also continue to increase the efficiency with which they use this energy.

We expect to see multiples in this market staying high and possibly rise further as the sense of urgency around climate change continues to increase.

Iain Gallow is a Senior Project Manager at Calash with over 15 years’ experience in the energy industry.

Recommended for you