The current collapse in the price of crude oil is the most extreme so far this century. It has already had significant impact on the oil industry, leading to some declarations of force majeure (examples include licenses and contracts in Iraq and the Gulf of Thailand). The question we address here is: what will the impact be on upstream producing countries? And more specifically, how should upstream countries react if companies approach them for fiscal concessions, citing marginal economics?

While not all eventualities can be covered in a brief note such as this, we offer some broad heuristics, or rules of thumb, for governments to consider in the current situation. They can be summarised as follows:

- Fiscal and tax relief should be considered in operating fields only.

- The onus should be on companies to demonstrate actual operating losses now and for some significant period into the future.

- The government should run their own analysis to understand the impact of price collapse based on the particular fiscal regime in place in each project, and the life stage of the project.

- Reasons for losses may play a part in government reaction to company demands for fiscal concessions: for example, if profits are in any case held low through transfer pricing and other tax optimisation strategies.

- Any measure should be on an interim basis only.

- There should be reciprocity on the upside, through adjustment of profit-sharing mechanisms for example.

- Transparency and accountability: any concession made by a government should be documented, quantified, and executed through a clear legal instrument, whether that is an amendment to the existing agreement, or by way of entering into a new set of arrangements.

Operating Fields Only

Any consideration of loosening the fiscal regime should apply only to fields already in operation. The current bear market has already seen several negotiations and new bid rounds postponed (for example in Brazil, Angola and Lebanon) as companies assess exploration and development risk against the new price environment. But the life of upstream petroleum projects is so extended that it would be premature to consider concessions either in bid rounds, or in concessions already signed but not yet in production. Upstream governments should only consider cases in which companies are actually losing money, not facing some potential of losing money in the future.

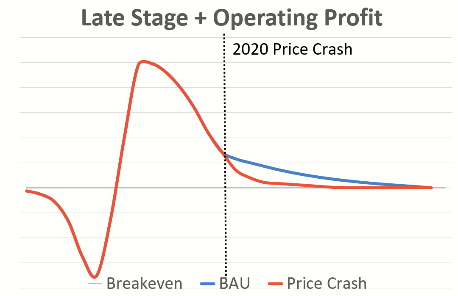

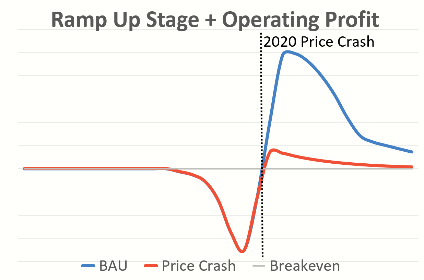

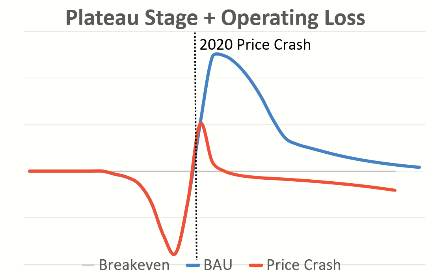

There is high variability in the way individual projects will be exposed to the price crash, as can be seen in the charts above of investor free cash flows from projects with different cost bases and life stages. In the chart on the left, the price crash makes little difference because the project is already in technical decline and the loss (gap between the blue and red lines) is relatively minor in terms of life of project economics. In the chart in the middle, where production has just started, losses from continued low prices are enormous. But the company will still keep producing as long as it is making any operating profit (the red line is above the breakeven line), since the capital phase is sunk costs and even if the project is loss-making overall, continued production is a way of trying to minimise the losses. The chart on the right shows a project at a production plateau. A higher cost base has pushed free cash flows below zero. If the company believes it looks like staying there, it must start to consider mothballing the project.

Government’s Own Fiscal Analysis of Status Quo and Any Change

Upstream governments should also reach an independent understanding of the impact of the price crash in terms of project economics and fiscal regime, in order to be able to make any determination in response to an approach by companies. Fiscal regimes can react very differently to a loss of profitability, depending on whether they are progressive or regressive and what life stage a project has reached: is it in early stage production (pre-plateau), plateau or decline? Have capital costs been fully or partly recovered? And so on. Entering into (re-) negotiations without knowing the own negotiation position, based on a fundamental understanding, exposes a government to either believe or discard the arguments of the upstream companies related to their attempt to change the commercial terms, which is not a good starting point for any meaningful and effective negotiation, that should be instead focused on exploring whether either of the parties could and should fairly request the sharing of the burdens imposed by the current price situation.

Reasons For and Scale of Losses: Harder and Easier Places to Make Concessions

Governments should also examine what the drivers of any operational losses are: from the commercial perspective an operational loss is arrived at by the sum of processes, both “real world” and financial, that are in play in the project. Does accounting loss involve transfer pricing, for example, which naturally reduces profitability in the upstream jurisdiction, or financing costs in highly leveraged operations?

Some kinds of fiscal concessions also play to upstream government interests more than others. Relief on payroll tax, for example, could address both operational losses and the need for projects to retain their skilled workforce. Relief on royalties, on the other hand, could strike at a central pillar of government revenues, and unless very tightly controlled could spill over into a bull market as much as a bear one.

Maintaining an overview of fiscal flows across the government is also important. Different agencies may have oversight over different revenue streams and this can be expected to influence the attitudes of these individual institutions. But “joined up government” is the key in the broader sense.

Interim Measure and Reciprocity

“There remains significant uncertainty around the recovery in the oil price and But some analysts already predict oil prices north of 100 USD per barrel with recovery starting from 2021 and any Government making concessions today, without getting a better deal in a different price environment or using the request for reshaping and renegotiations by the upstream companies as an opportunity to analyse and reshape the overall relationships into a better partnership between upstream government and upstream company will have missed a chance. As stated above, when entering into negotiations it is essential to know ones position. Once the government understands the implication of any concessions requested based on its own models and analysis and the discussions with upstream companies, it can and should settle for fiscal adjustments that are flexible and apply in a challenging price environment only, will be reversed automatically if the market changes, and ideally improve their terms (whether fiscal, commercial, or with regard to the overall partnership with the upstream companies in areas such knowledge transfer, real local content, and others) in a bull market.

Transparency and accountability: Legal Mechanisms and Process

Any concession made should be thoroughly documented, costed, and established through a clear legal instrument, with a defined scope, including, by default, a defined time period. This can be achieved by way of amendments of existing contracts and licenses or, for example were the existing documents in a country are outdated and for new project have been replaced by new documents and approaches, by engaging with the upstream company on the basis of these new documents. Although there is huge pressure on all stakeholders involved, hasty negotiations and quick concessions may turn out to be at the long term detriment of the government and may even by, rightfully or, questioned by any successor government or the public. If a government follows the steps recommended in this article, it should be well equipped to have focused discussions and negotiations with the upstream companies that can be easily documented and communicated to the broader market and the public, with maybe even having a welcomed positive side effect of stronger relationships ion the long term with the upstream companies. This kind of quantifiable and documented approach, with clear, public and measurable criteria, is also what will protect governments against any liability from bilateral or multilateral investment treaties which require equal treatment of investors.

As stated at the beginning of this article we are focusing here on operating fields only. The situation during the exploration phase is different and will require a different approach. OpenPoil is currently working on a number of case studies in this regard

Authors

Johnny West, Founder and Director, Openoil,

Alexander Sarac, Energy and Infrastructure Partner, Addleshaw Goddard Dubai.

Eleanor Morris, Energy and Infrastructure Associate, Addleshaw Goddard Dubai.

David McEwing, Energy and Infrastructure Partner, Addleshaw Goddard UK.

John Podgore, Energy and Infrastructure Partner, Addleshaw Goddard Dubai.

Recommended for you