As the dust settles on another budget, and the “Granny Tax” occupies fewer column inches, it is good to reflect on where we are in the evolution of the UK Continental Shelf (UKCS) fiscal regime.

Last year’s budget was one that elevated that regime to the front page of our national press, and caused some inbound investors to compare UK fiscal policy very unfavourably with other countries in which they invest.

It was the third unwelcome and unexpected change in nine years; and seemed worse because it came from a coalition government who, on taking office, had expressed an understanding of the significance of the oil and gas sector to the UK economy.

Shaking investor confidence for the third time in less than a decade was not a clever thing to do; and it certainly gave the impression that, in the mind of government, stability or predictability are not essential components of the UK’s regime.

In contrast, successive governments have seen the benefits of a competitive general tax system and have introduced changes over the past decade which is making UK Corporate Tax one of the most attractive in world.

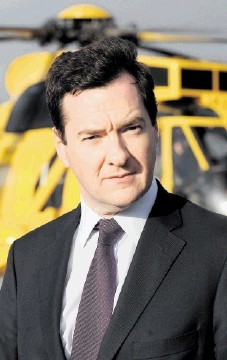

Whilst Chancellor Osborne has never admitted that political expediency rather than principle lay behind last year’s budget, the 2012 event suggests that the coalition is anxious to arrest the UKCS production decline and acknowledges, even with high commodity prices, many potential investments on the UKCS need support when the tax rate is 62%/81%.

Much of the credit for this perceived shift in the Government’s thinking lies with industry and its body Oil and Gas UK (OGUK). Individual leadership, along with cohesive action from OGUK, has ensured that both the cost of tying up resources in decommissioning securities, and the potential loss of investment in certain prospects is likely to be addressed.

In the budget of March 21, the Government announced that it intends to bring forward legislation in the next Finance Bill which will enable it to enter into contracts with companies to underpin the level of tax relief that these companies will receive when they decommission assets.

There will be a period of consultation to establish the precise details of the contract. There will also be some tax changes to ensure that the overall package achieves the intended result of enabling decommissioning security to be provided on a post-tax rather than pre-tax basis.

Such a change should enable more UKCS assets to change hands and free up capital that would otherwise be tied up in decommissioning guarantees.

A review of a number of asset transfers in recent years supports the position that when an asset changes hands investment in the asset increases, recoverable reserves rise, and the asset life is extended. As there were a number of potential dispositions of UKCS assets last year that did not go ahead, it is hoped that deal activity will ramp up considerably.

In addition to the decommissioning security changes, the latest budget included a new category of field allowances, for “deep, sizeable fields”; essentially targeted at West of Shetland prospects.

The allowance is £3billion, which as it is given against supplementary charge translates into cash at a rate of 32%, so reduces the overall tax take from Frontier fields by £960million.

There were also changes to the existing small field allowance: the allowance will now apply to fields with reserves of up to approximately double the existing allowance, and the allowance itself is doubled to £150million.

Furthermore, there is the potential for some fiscal assistance to existing fields with the Government announcing that it will introduce appropriate primary legislation such that it can then introduce an allowance for such fields by statutory order in the future.

Whilst this is helpful, it demonstrates that the Government is still unconvinced on the structure of this incentive.

That is most likely because of concerns on how the allowance can be targeted.

Whilst Industry can demonstrate specific cases where an allowance is required, it is very difficult to demonstrate to the same standard of proof that the allowance won’t also then apply to another field that is undeserving of assistance.

This so-called “deadweight” issue has dogged the debate on mature field incentives for years and while progress has been made, further work is necessary to formulate a suitably targeted mechanism to deliver the incentive.

That brings us to an appropriate point where we should review the current regime from afar.

Despite Petroleum Revenue Tax (“PRT”) being abolished 19 years ago, it is still alive and well for many of the older fields in the North Sea.

The companies participating in such fields know the unrivalled joys of cost apportionments, tariff receipts and tariff receipts allowance, exempt tariffs, non-qualifying use and so-forth.

Even those not in PRT fields now have Corporation Tax at 30%, Supplementary Charge, various forms of capital allowances, special debt funding rules, special valuation rules, and ring fence chargeable gains to deal with.

Overlay on top of that field allowances for small fields, slightly bigger fields, ultra-HP/HT fields, heavy oil fields, remote gas fields, deep and sizeable fields and possibly brown fields – it all makes for a very complex fiscal regime.

Tempting as it may be to simplify, it has proved impossible to do so without creating winners and losers, or giving rise to deadweight. Therefore, it is here to stay for the medium term.

In the meantime, Industry must remain in regular engagement with HMT to ensure that we fine tune the regime to promote investment and steer clear of any further tax shocks. It is doubtful even the most long-term investor could tolerate such a change in the foreseeable future.

Derek Leith is senior partner at the Aberdeen office of Ernst & Young (dleith@uk.ey.com)

Recommended for you