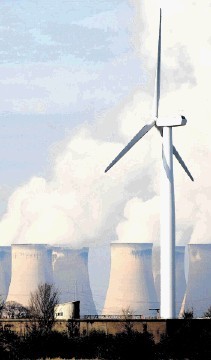

Coal is often treated as the embarrassing relation of the energy family. Everyone depends on it but would prefer not to say so. It neither courts headlines nor receives plaudits – but without it, the well-worn phrase about the lights going out would soon turn to reality.

Renwables are sexy, nuclear has huge potential, gas was supposed to be the quick fix. But actually, it is coal that still provides the backbone of the UK’s power supply in spite of all the rhetoric about moving towards a low-carbon economy. That movement comes only in fits and starts, as dictated by market conditions.

Remarkably, this fuel which is supposed to be on the way out as we all pay lip-service to a greener future accounted for 46% of UK power generation in Q1 this year – the highest proportion since 2006. During the same period, the share coming from gas fell to 25% . . . the lowest for 25 years.

These statistics stand popular perception and political correctness on their heads. We are supposed to be moving towards a low-carbon economy, are we not?

Well, “yes and no” is the answer. As long as the market has a hand in these decisions, the generators will go for what is cheapest (or most heavily subsidised) at any given time, rather than being guided by environmental imperatives far less political preferences.

And recently, coal has indeed been cheap on world markets. So imports have increased dramatically and, while printing their press releases on environmentally-friendly stationery with green borders, the generators have been making vast amounts of cash by the simple expedient of switching gas stations off and bringing coal-fired stations back to full-blast production, particularly in the south close to main markets.

Parodoxically, the coal boom has not been great news for the UK’s indigenous coal producers who find themselves at a substantial price disadvantage compared to the imports from countries like Colombia, Australia and – our main source – Russia. Indeed, production of domestic UK coal fell 12.3% in Q1, partly due to the closure of a couple of deep mines.

Compare this to the boom in imports. We imported 3.64million tonnes of coal in May alone – the highest monthly figure for three years and 75% up against the same month last year. In the first five months of 2012, coal imports rose 40% compared to Q1 last year. And you still tell me that coal is on the way out?

While giving the generators a short-term profit boost, this dash for coal is storing up a few interesting questions for the future. A quite urgent one is whether either the Scottish or UK Governments can remain as spectators while what’s left of the indigenous coal industry is eroded by price competition from cheaper sources – irrespective of how temporary that cheapness might be.

In Scotland, that debate is not only about the wisdom of import-dependency. It also involves a few thousand direct and indirect jobs, many in areas where there are few alternatives. Although our deep-mining industry no longer exists, coal is still a relatively big player in the Scottish industrial economy.

Looking slightly further ahead, there are also a lot of questions begged by the proposed Energy Market Reforms and how they will impact upon the coal contribution. On the face of it, the answer is not encouraging for the coal generators with new penalties being introduced for coal-fired stations, alongside the environmental regulations which are forcing them to clean up their act.

There will be no new coal-fired stations in the UK which do not incorporate Carbon Capture and Storage infrastructure. That has been anticipated for some time. More significantly, existing coal-fired plants will see their competitive position deteriorate as lower variable-cost generating plants are added to the system and higher carbon emission costs favour gas-fired generators.

From an environmental point of view, that sounds fine and dandy. But what will it do to the price of electricity for the consumer? Even now, with “cheap coal” providing such a large proportion of our power generation in recent months, there is still upward pressure on prices, as evidence by SSE’s announcement of a 9% hike, to be followed by others.

The more that coal is forced out of the mix, the less flexibility there will be for generators and the more vulnerable we will become to sharp increases in other commodity prices, notably gas. While unabated coal-fired generation clearly has no part to play in future thinking, it seems to me that caution is required in just how much of the coal-based contribution is effectively displaced from the mix.

I have long argued that we should pursue Carbon Capture and Storage because, globally, the prize would be so great if the coal-burning world was persuaded to adopt it.

The same applies to other, more immediately available strategies for reducing emissions from coal-fired stations. Coal is such a ubiquitous fuel, dominant in so many parts of the industrialising world, that persuading countries to use it in a more environmentally-friendly way is going to produce far greater carbon-reduction gains than probably any other strategy.

But there is also another side to that coin, and it might be time to consider it. Draconian measures against coal-fired generation in this country alone will have minimal impact on global carbon reduction statistics but could have an entirely disproportionate impact on the benefits we currently accrue from having coal as part of our energy mix. We should proceed with caution in surrendering these.

And if you doubt the continuing importance of coal to every aspect of the energy debate – including affordability and security of supply – just remember that 46% statistic.