It’s great being proven right. I’ve long argued that who owns the companies that make up the energy, or indeed any other, sector is important because if you don’t own it then you simply don’t control it. The free market ideologues argue that it doesn’t matter who owns what provided the jobs are anchored here and it’s that attitude which has prevailed in the UK for the last 40 years or so.

So far, merger and acquisition activity in the energy sector has tended to support the free market view but that all changed recently with the announcement that the wave energy company Wavegen based in Inverness was being shut down, its 18 employees were being made redundant and – importantly – all its activities were being moved to its parent company in Germany.

The parent . . . Voith Hydro, of Heidenheim in Germany, say it’s their intention to “pool the Know-How” at the company’s engineering centre which essentially means Wavegen is being intellectually asset stripped.

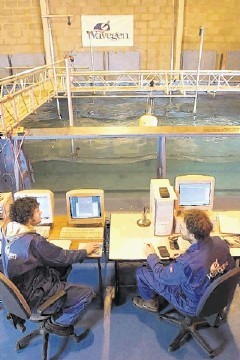

Of course, it’s not as if Wavegen was a failure. In fact, it designed and built Limpet which uses Wavegen’s OWC (oscillating water column) technology. Limpet is the world’s first commercial-scale, grid-connected wave energy plant. It has an installed capacity of 500kW, was commissioned in November 2000 on the isle of Islay and has been supplying electricity to the grid ever since.

Wavegen also supplied the technology Spanish utility Ente Vasco de la Energía (EVE) use for their wave power project at Mutriku on the Bay of Biscay. The plant was commissioned in July 2011 and will generate an output of 300kW to power 250 households locally.

This then all sounds like good news. Here is a small hi-tech company doing some extremely smart stuff in the marine energy sector and even exporting its technology. Just what we’d all hoped from the renewable sector although, of course, it took the support of German funding to get it moving along properly after Voith bought the struggling company in 2005.

Despite its potential, Wavegen along with countless other companies found the raising of funding in the UK to be a major obstacle. This is not unusual, sadly.

So what triggered Voith’s decision to kill off Wavegen and retreat to Germany? Voith claims the decision was part of its plans for “re-organisation”.

However, the company was developing the Siadar Wave Energy Project on the Isle of Lewis in the Outer Hebrides which used an “active breakwater” designed to harness power from the Atlantic waves in Siadar Bay. The project was for 4MW with a second phase that would expand the output to 30MW. The objective was to export most of that energy to the mainland – in this case via an HVDC (high voltage direct current) cable.

But, in 2011, one of the project’s main investors – the German company RWE – pulled out and one of its spokesman said: “Tidal seems simpler to develop and it’s going to be easier and quicker to develop than the Siadar (wave) technology.”.

Given the technology has already been proven this appears to be a quite bizarre excuse and frankly, I have real difficulty in believing it.

Then in late 2012, it was announced that the cost of that HDVC cable had risen by a mighty 75% to at least £700million. Needless to say this effectively signed the project’s death sentence and along with it the loss of over £5million of public sector investment.

Highlands and Islands Council have quite rightly said that questions do need to be asked about the costs and the time scales involved in laying the HVDC because it would have allowed other renewables sources such as wind to transmit power to the mainland.

I also think the Scottish Government should take a look at this project. While £5million or so worth of grants won’t break the public sector bank and I believe in the public sector supporting projects like this I can’t help but feel that we need to better understand what went wrong.

Of course, you can’t prevent private sector companies pulling out of a project if they’re not happy with it but I would really like to know why RWE entered into the deal in the first place if its people were so unsure of the technology. Seems to me they had plenty of opportunity to make that assessment before signing on the dotted line.

I’d also like to know why this project was aimed mainly at exporting electricity to the mainland. Why not go for the local market and aim to achieve energy autonomy for the Western Isles? Perhaps they might even have looked at using the Western Isles for trialling a range of new technologies including using some of the energy produced by the Siadar project to run electrolysers producing hydrogen for use as a transport fuel or as a means of storing energy by converting the hydrogen into ammonia feedstock, so making it easier to contain safely.

Perhaps a little more imagination and forward thinking might have made this a more affordable and beneficial project both in terms of what it would bring to the peoples of the Western Isles, the renewables industry in general and of course, Scotland’s industrial scene.

I say “perhaps” because, of course, nobody can tell whether the outcome would have been different or whether Voith Hydro – Wavegen’s owners of late – ever had any intention of doing anything but absorb the Wavegen “knowhow” into its German-based headquarters and shutting the Inverness base down.

Regardless, it should teach us a lesson. Scotland has now lost the economic potential that Wavegen represented as well as the jobs of some talented people.

This was a small company but a very smart one with a clever set of proven technologies. That we allowed Voith to buy it in the first place was extremely careless but, of course, given the attitude of our glorious financial sector towards funding companies like this it wasn’t surprising.

It would be nice to say this is unlikely to happen again but a number of ostensibly “British” renewable technology companies are now already foreign owned or have majority overseas shareholders. So we need to be alert to the possibility of more losses of this nature although, of course, we won’t stop this until such time as the bankers et al adopt a different culture.

Yes I know – pigs might fly.

Recommended for you