When the Energy Bill was published in May last year, I wrote here that it seemed a decent attempt to address the intractable challenge of how to incentivise the switch to low carbon generation while at the same time keeping the lights on and the bills just about affordable.

Now that the Bill has passed its House of Commons stages and some flesh has been put on the bones, I stand by that initial benefit of the doubt. The fact that MPs voted by 396 to eight in favour of giving it a fair wind suggests there is a consensus view that it is trying to do roughly the right things.

Now it is up to their noble Lordships to subject it to detailed scrutiny over the next few months during which time more details will emerge about the subsidy regimes for various technologies under the Energy Market Reforms which the legislation will produce. Both the renewables and nuclear industries continue to lobby anxiously.

The main criticism of the Bill, both inside and outside Parliament, is that it has failed to incorporate a decarbonisation target for the power sector by 2030.

Prior to the Bill being given its large Commons majority, an attempt to introduce an amendment in favour of such a target failed by only 23 votes with some Tory and Lib Dem MPs voting against the Government.

I can’t summon much sympathy for their cause. The landscape of this whole debate is littered with targets and the idea that the addition of another one is going to make any substantive difference is unconvincing.

Target-setting is too often a short-term substitute for actually doing anything – and those who set the targets are rarely around to be held accountable.

The UK is already legally bound to cut emissions by 50% across the whole economy by 2025 against a benchmark of 2010. And we are committed to cutting emissions by 80% between 1990 and 2050.

These commitments are driving the policies which the Energy Bill is intended to give substance to. But it is now actions and their impacts that matter.

Various green critics argued that the failure to set this target would discourage investors from supporting renewable technologies in the UK.

Frankly, this is nonsense. It is not targets that investors are interested in but profits – and the profitability of renewables will, for the foreseeable future, depend on the level of subsidies rather than on hypothetical targets.

It is this transition from the Renewables Obligation system to one based on contracts for difference which continues to pose massive conundrums for the authors of this legislation.

There are two ways of getting it wrong – either they can indeed disincentivise investment through a cautious approach or they can underwrite massive and unreasonable profits by listening to the lobbyists. I sympathise with the challenge of getting the balance right.

The other area of continuing uncertainty is the support regime for nuclear new-build, particularly on guaranteed pricing once the stations are finally on-line.

Here too the stakes are high – there are only a few projects still on the drawing-board and the decisions taken will either kill them off or create a platform for development. I hope it is the latter since we need new nuclear-build.

Of course, the debate is complicated by the fact that many of the most vociferous green lobbies hate nuclear as much as they love renewables, so they are not interested in the level playing-field which Government will attempt to establish.

Yet anyone whose true priority is a low-carbon future must accept, however reluctantly, that nuclear and renewables are two sides of the same coin.

The crucial question about the future sources of our electricity is not just how it is generated but, equally important, what it replaces. If renewables replace nuclear, there is no net gain. If gas replaces nuclear, there is a net deficit – and so on.

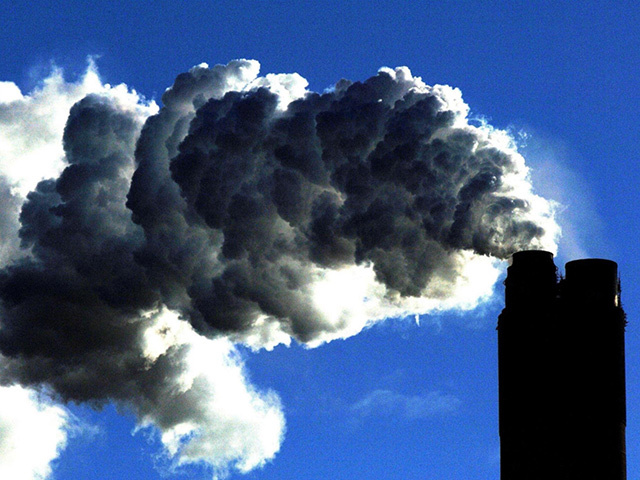

At present, carbon emissions from power stations are increasing because fossil fuels, more-so than renewables, are replacing the declining nuclear output.

Gas is also a huge part of this jigsaw. So long as it is replacing coal-fired generation, gas is contributing to a carbon reduction agenda. But if it is allowed to become dominant in the mix it will also be forcing out nuclear and renewables.

That is the direction in which the short-term market logic is pushing but Government has to find ways of resisting it – another aspect of the legislation which needs strengthening.

Among the bodies demanding 2030 decarbonisation targets, I was a bit surprised to find Fuel Poverty Action on the grounds that “fledgling low-carbon technologies”, if developed, would actually save consumers money.

I fear that this theory is so tendentious as to be worse than useless for households currently suffering from the reality of electricity bills they can’t afford.

However virtuous decarbonisation targets may be in other respects, they certainly do not come cheap – and it is consumers who pay. This too is part of the dilemma for government. It cannot both demand that prices are kept down and at the same time give open-ended commitments to technologies which, at least in the short-term, involve huge consumer subsidies and billions of investment in new infrastructure.

All in all, I am prepared to accept that an honest, balanced attempt is being made to turn these competing factors into a coherent structure – which may or may not determine the reality which will actually exist in 2020, far less 2030 or 2050.

Recommended for you