It’s a part of life … every second of every day, myriad people are handled unfairly, wittingly or otherwise.

They may be treated less favourably or, worse, discriminated against because of their age, disability, ethnic origin, gender, ideology or religion, or sexual identity.

This is despite more than 75 years since the United Nations adopted the so-called Declaration of Human Rights.

In the EU, the European Convention on Human Rights, Article 14, specifically protects citizens of the Union and, for a time at least, post-Brexit Britons too.

It states that rights and freedoms “shall be secured without discrimination on any ground such as sex, race, colour, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, association with a national minority, property, birth or other status”.

Yet people are still discriminated against every day and it takes many forms.

Much is institutionalised, even in countries that we in Britain have long regarded as being socially more advanced than we are.

In particular Norway where it took legislation to begin to sort out the gender imbalance issue in the early years of that country’s offshore oil & gas industry and wider business community.

It is this aspect of discrimination that first captured my attention as a journalist in the ‘90s because it angered me that so few women worked offshore and almost none were bosses.

But the spark was in reality ignited in the family home decades earlier.

Both parents were highly qualified. However, even though my mother was a bacteriologist and held things together financially in the 1950s whilst my father stacked up various degrees, her career was sacrificed.

She became a mother of four offspring; condemned to putting up with long overseas absences by our father who worked for FAO, etc.

She had served in the Women’s Land Army during WW2, slaved on the family farm until the family temporarily left the UK for foreign parts and knew a lot about social history.

Including that, on a Friday, coal miner’s wives would wait at the door for their menfolk to come home and surrender their pay-packet into the apron.

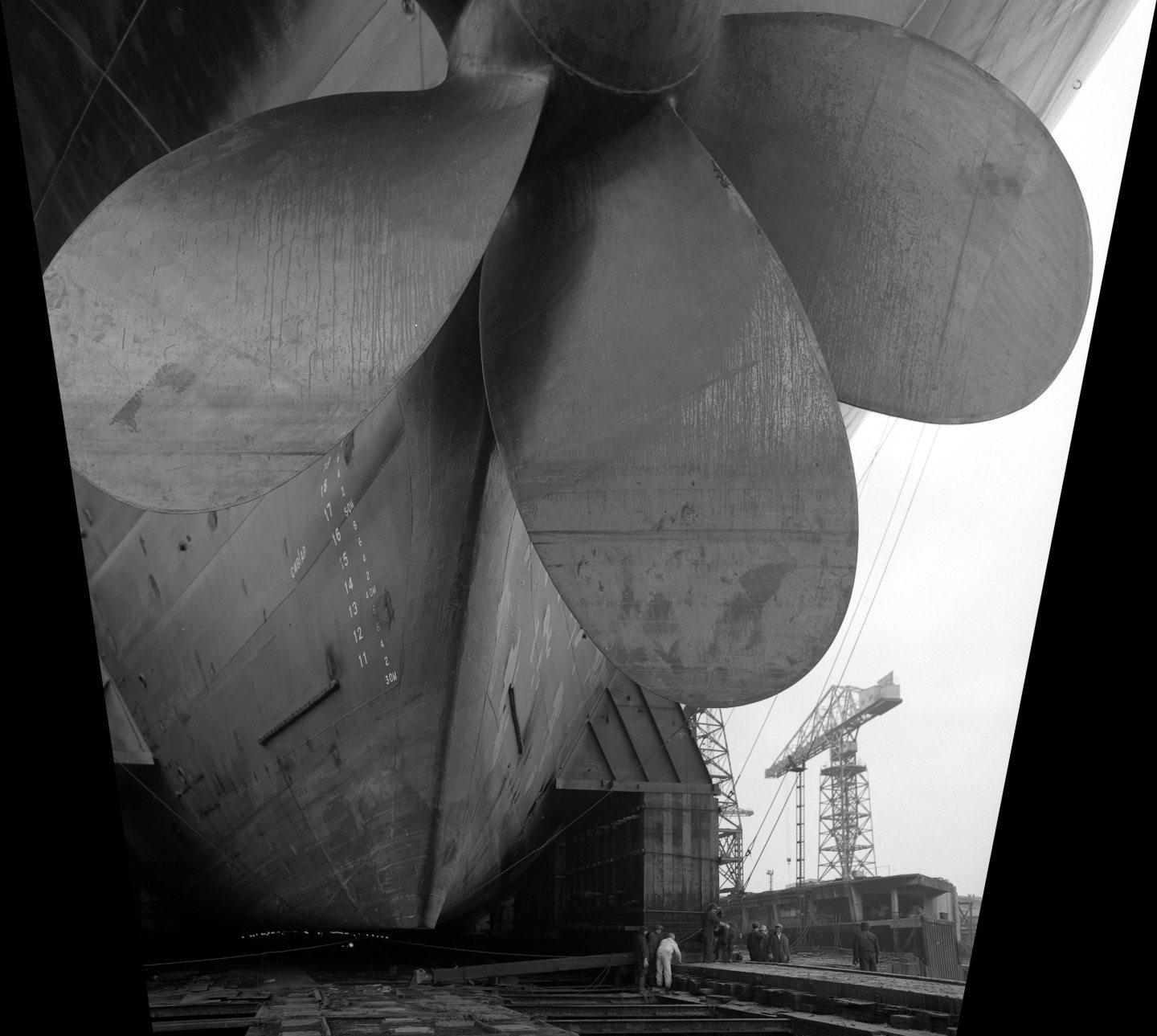

Same for shipyard workers. My granny Nora Jane Cresswell ran her house with a rod of iron and George Edward Cresswell, who worked at Swan Hunter on Tyneside for his entire life, toed the line.

Nora Jane never got the opportunity to work and if she had it would have been skivvying or suchlike.

So it was at a relatively early age that I became conscious of the gender issue and one that I have pursued for a long time through the pages of the Press & Journal and Energy.

The argument is simple. Women make up half of the adult population and yet they get a raw deal; even in new industries like renewable energy.

In 2020, Big Wind’s laggard status in representation of women emerged in a study by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) that found women making up just 21% of the industry’s workforce, well behind 32% in renewable energy as a whole but close to the 22% of the oil & gas sector.

The wind situation has since deteriorated. By early this year the proportion was down to just 18%; compared with around 25% for North Sea oil. And so, in May, the Offshore Wind Industry Council (OWIC) and the University of East Anglia (UEA) launched a joint research project, called “Clearing the Pathway for Women in Wind”, to boost the number of women working in the offshore wind sector.

The project is part of the UK’s Offshore Wind Sector Deal and includes a commitment to ensure that women make up at least 33% of the workforce by 2030, with 40% as a stretch target.

But what about the other five issues that hamper diversity and inclusion efforts. To remind, they are: age, disability, ethnic origin, ideology or religion, or sexual identity.

My perspective is that, in the UK, each of these can best be summed up as work in progress but struggling. Legislation to force change has at best been only a partial success. The fight for equal pay is a spectacular example of failure; one driven by a still all too prevalent chauvinistic corporate culture.

Last year, Oil & Gas UK issued its inaugural report into the state of diversity and inclusion in the industry, covering race, age, sexual orientation, disability and other demographics.

The report, which underlined that gender is only a part of the diversity and inclusion conversation, showed that, even with equal recruitment going forward, the populations of men and women in the industry won’t reach parity until “well into the 2050s” at current rates – ninety years after it began.

So, if it’s going to take the thick end of a century to reach even basic gender parity, what the hope is there of making even reasonable progress with the multiple issues that comprise diversity and inclusion.

Will the renewable industry take just as long?

Recommended for you

© Supplied by DC Thomson/ Commando

© Supplied by DC Thomson/ Commando © Shutterstock / Peter Loud

© Shutterstock / Peter Loud