Recent proposals by the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) on electrification of the UK North Sea could risk development of over 900 million barrels of oil equivalent and increase the UK’s reliance on higher intensity imports.

It is proposed that fields onstream after 1 January 2030 must be fully electrified (host platforms must be electrified in the case of tie-backs). New fields onstream before 2030 must be “electrification ready”.

However, the economic feasibility of all electrification models has still to be fully tested. Electrification readiness (which needs defined) and full electrification should only be required if there is reasonable certainty it can be delivered. Otherwise, the proposals risk stranding new domestic supply in favour of imports.

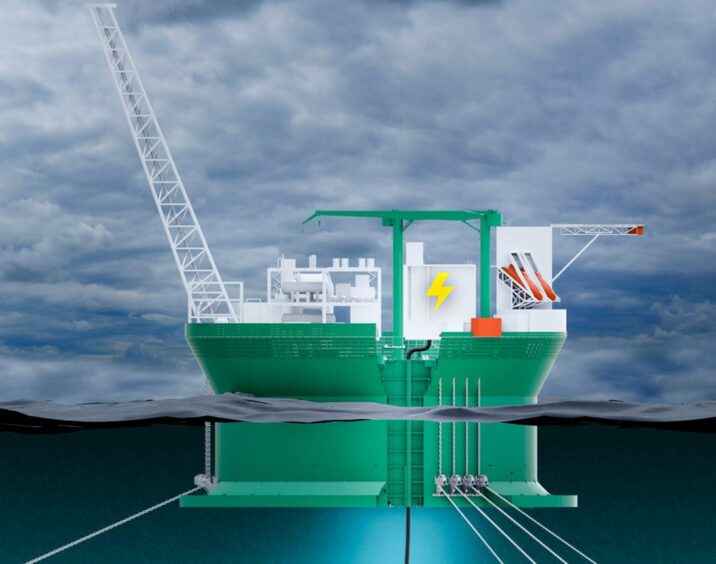

According to the NSTA, power generation represents 79% of total UKCS emissions. Feasibility studies are assessing the suitability of electrification from shore, while the Innovation and Targeted Oil & Gas (INTOG) offshore wind leases awarded last year in Scotland, are targeting platform electrification via offshore wind. But in either scenario, electrification presents limitations that upstream operators cannot control.

In the UK, fossil fuels comprised 36% of grid-connected power generation in 2023. While this will decline, electrification will never deliver 100% upstream emissions reductions on power generation. Even with coal completely phased out in 2024, the UK will continue to rely on piped gas and LNG to balance the market.

Grid electrification will mean operators importing power partly generated from their own North Sea gas. Platforms supplied by offshore wind would still have to operate thermal turbines and spinning reserve capacity to maintain power 24/7.

The North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) has consulted industry on further reducing UK upstream emissions. Operators must reduce emissions 50% on 2018 levels by 2030. The NSTA believes this target will be missed unless more is done. Its key proposals are:

· Full electrification of fields onstream after 1 January 2030 (host platforms must be electrified in the case of tie-backs)

· Fields onstream before 2030 to be “electrification ready”.

· New developments shall have zero routine flaring and venting

· Zero routine flaring and venting for all developments by 2030.

· Declaration of cessation of production (COP) dates for fields with emissions intensity 50% above the basin average

Indeed, analysis suggests electrification could abate 15 MtCO2e from 2030 to 2050. Based on our estimated Scope 1 & 2 emissions (with no electrification), that would cut total emissions from power generation by just 41% across the period.

Grid electrification lead times are another problem. The proposed electrification of the Central North Sea from shore won’t happen until the early 2030s at best. And with many of the key hubs expected to cease production before 2040, every year that passes narrows the economic window.

Given the limited gains, costs and lead-times involved, the desirability of electrification in a mature North Sea, particularly from the grid is questionable. It could be argued that a much better use of renewables is to decarbonise households and businesses in the UK, since these make up 95% of all emissions.

Legacy oil and gas assets could be wound down as safely and cleanly as possible. Operators that can make offshore wind work on their assets, do so without impacting the transformation of the national grid and the challenges that might entail.

A focus on supporting industries with a longer-term future such as carbon capture and storage , would be a good alternative for larger players, while smaller producers could for example, contribute to a UK decarbonisation fund that could pay for home insulation on a national scale. There are reasonable alternatives large and small, that could be more effective.

This is not letting industry off the hook. The proposals are tough and could leave hundreds of millions of high-intensity barrels in the ground through early cessation. As the NSTA rightly states, the social licence to operate is fundamental to maximising economic recovery. But there is a difficult balance to be struck between meeting these objectives and limiting imports of high intensity barrels.

Recommended for you