On the Obama side of the Atlantic, several rounds of opaque negotiations have been going on since July 2013 in order to father a USA-EU transatlantic trade and investment partnership, or “TTIP”.

The target is to conceive a free-trade agreement that would remove custom barriers for over one trillion USD of transatlantic trade and four trillion USD in investment. Even if arguable, NAFTA’s trade achievements serve as backdrop to the negotiations around the TTIP. Since 1994, NAFTA has massively grown trading volumes between the USA, Canada and Mexico. NAFTA’s cumulative impact on employment and the creation of promised new jobs remain, however, difficult to gauge.

Still, NAFTA’s official praise help Washington adorn the TTIP’s negotiations with hopes that the TTIP-to-come could translate into a similar fate for Europe. Visionaries promise that progressing on harmonized standards and regulations will make the TTIP’s signatories more globally competitive. The TTIP will primarily redefine international trade rules.

On the Merkel side of the Atlantic, the TTIP’s positioning as the new economic treasure trove is being received with resounding scepticism. With the exception perhaps of the UK, many amongst Europe’s 28 are weighing the prospect of more transatlantic trade against concerns over the TTIP’s impact on local identity, civil society, privacy and European values. Currently, the Commission is conducting negotiations for EU according to a specific mandate. Yet, as European law requires, the European Parliament will also have co-decision on the TTIP’s final draft.

Relaxing transatlantic export rules on energy products would introduce a flexibility that could alleviate the Russia-EU energy tripalium. The TTIP would certainly transform, if not remove, the USA’s current licensing requirements for LNG export to its non-free trade partners in Europe.

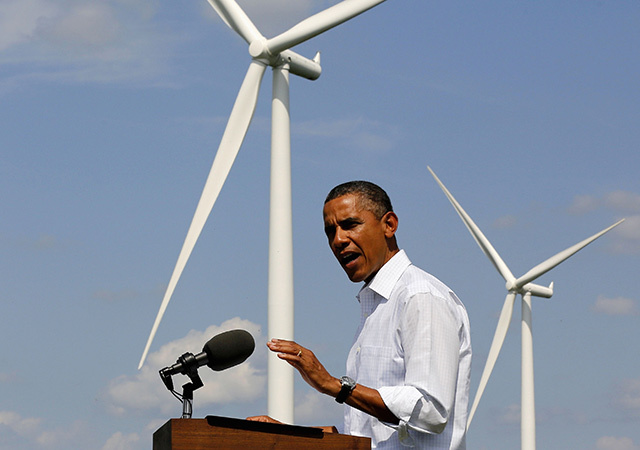

Visiting Warsaw earlier this month, president Obama’s comments on the TTIP led him to elaborate on geopolitics and the likely impact of the future treaty. With Ukraine in the back of everybody’s minds, this future free-trade agreement should make a strong impact on the current trading patterns of energy products. Within a few years, this arrangement would be likely to enhance competition and open real alternative LNG supply routes.

Now in America, LNG plants are being converted in order to export a good share of the USA’s massive shale gas output. For the American president, the TTIP would provide Europe with the ideal framework for an instant energy security solution. Russia would be forced to review its current energy ambitions still largely resting on the rent it is collecting from Europe. It is not unreasonable to think that the 2014 Ukranian context has helped recently finalize the 400 billion US dollar deal between China and Russia which took 10 years to negotiate.

This new supply route to China could, however, cause a gas surge in Asia and lead to re-route other LNG suppliers to other markets. The ensuing global downward pressure on gas prices could be good news for Asia and China. China could also contribute to this future pressure on gas prices and oversupply as, just like Argentina, it is now seriously moving on shale gas. Lower gas prices may, however, be less of a good news for Europe as massive investment finance will be required to support the new transatlantic LNG infrastructure. With gas market price going down, capex and investment will also go down. This is a basic economic rule to which the energy industry is certainly no stranger.

A key point of contention hovering over negotiators, however, is the treaty’s future “investment protection and investor-to-state dispute settlement” mechanism, aka ISDS. Similar dispute resolution provisions exist in virtually all of the 2,600 bilateral treaties now in place around the world. They aim to provide an objective, fair and non-politicized forum for investor-state disputes. The ISDS however gives fuel to the TTIP’s opponents. They are suggesting that this treaty could lead foreign investors to challenge the EU Member States’ future legislative frameworks that could or would frustrate foreign investors’ interests.

Governments would thus loose a degree of sovereign discretion on new laws as proven negative impacts of legislation on investments could end up being sanctioned through private litigation initiated before the TTIP’s appointed dispute resolution forum. Gradually, fears arise that the sovereign act of governments and parliaments to introduce new legislation could translate into states having to pay damages to frustrated investors who would seek redress through a private, confidential and final mode of dispute resolution.

Such an exposure could create a strain on public finances and raise the cost of, if not hinder, democracy. It is not the first time that a treaty with a core energy dimension hits a nerve by holding back WTO-style free-trade partners on issues of dispute resolution. In 2009, the investment dynamic underlying the Energy Charter Treaty (ECT) suffered a serious set back when Russia chose to withdraw from its “provisional application” of the said treaty.

By pulling out of the ECT, Putin’s federation precisely turned its back on an ambitious framework that would regulate its members’ investment, trade, transit and dispute resolution by private settlement and/or arbitration of energy investment disputes. At a time when the TTIP’s negotiators are facing a critical juncture on dispute mechanisms, they should certainly reflect on Russia’s rejection of the ECT and its impact on cross-border energy investments. A successful TTIP on such and other provisions would also provide Washington with a brand new successful precedent, fresher than NAFTA, which would help boost the Trans-Pacific Partnership negotiations America is also painstakingly trying to finalise with its future free-trade partners of the Pacific region.

Recommended for you