Last month, I discussed the challenge of the severe weather associated with hurricanes. We were reeling after an early storm struck Scotland, with some rigs in the North Sea recording 9m (30ft) seas. Since then we have been enjoying a warm, dry September, though sea-fog impacted offshore flights.

But what was summer 2014 like? Was it “good”? It also begs the question – can seasonal weather be forecast, and can anyone tell us what to expect this winter?

June and July were relatively “quiet” due to a “slack” surface pressure gradient across Scotland and its waters.

A weak easterly to north-easterly airflow meant light winds and moderate seas; all good for offshore construction and maintenance campaigns.

August was livelier, with a cyclonic (low pressure) pattern extended west of the UK and into Scandinavia. Prior to August 10, vigorous ex-hurricane Bertha tracked rapidly across the Atlantic, before crossing the UK and drifting northwards into the North Sea, so affecting all maritime operations.

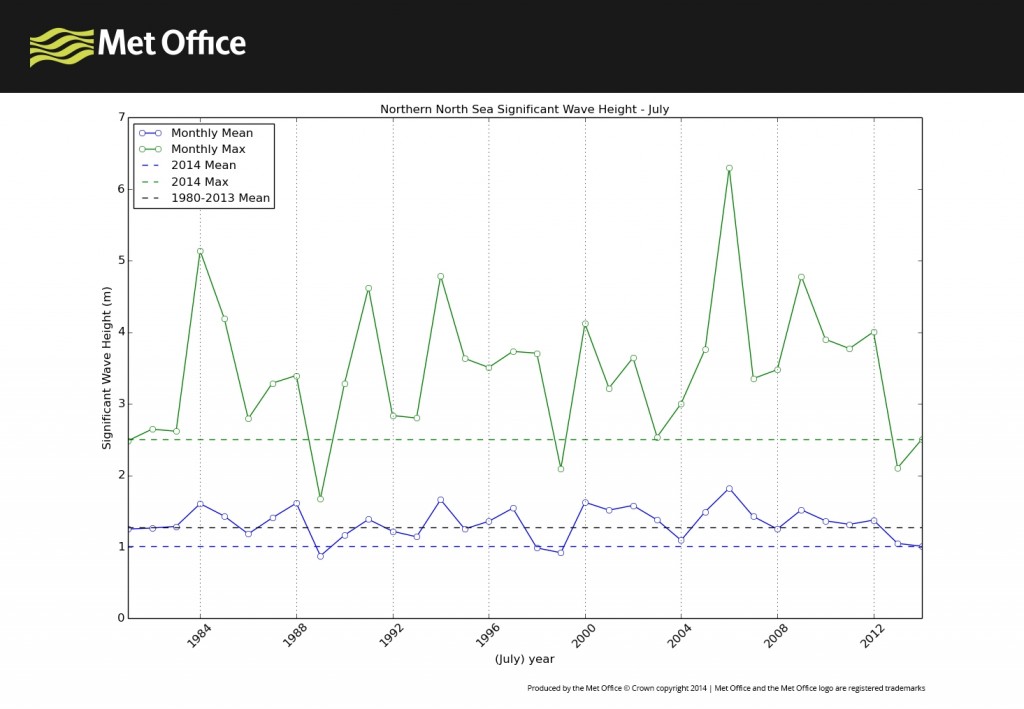

So how big were the waves? Provisional analysis of wave heights drawn from the Met Office hindcast data-set show that the monthly observed averages for site-specific locations in the Northern, Central and Southern North Sea were average or lower than the averages for June and July over the last 34 years. However, August wave heights and wind speeds were above average.

Anyone operating in the North Sea will tell you that no year is like another and that it is important to note the variability from one to the next. Such knowledge is important to operational strategy.

In the late 1970s. I remember working with a forecaster compiling a weather chart for a month ahead – which at the time, was a long-range forecast. This chart was aimed at helping an exploration company plan its longer term operations in the Central North Sea.

Since the early days of forecasting there have been huge advances in computing capacity. In addition to the development of ocean and atmospheric knowledge and prediction models, and aligned to recent developments in climate prediction science, these advances mean that seamless “weather” predictions can now be made a number of months ahead.

The format is different to those that provide an answer to what is the weather going to be like on a given day. It would be daft to suggest we can forecast what the weather will be like on a given day in a couple of months’ time, and for two main reasons.

Firstly, there are elements of the earth system (such as the oceans, moisture content of the soil and coverage of sea-ice) that evolve more slowly than the atmosphere, and influence its behaviour.

Secondly, seasonal forecasts have to consider a longer time span, and need to be presented in a probability format, and also related to an average climatology (the “normal” weather) calculated over recent decades.

For example, rather than asking what the weather is going to be like on a specific day, in seasonal forecasting we try to address questions like: if the average temperature in Scotland in January is 4C, what is the likelihood of having warmer or colder temperatures this year?

Our long-range forecasts are produced using data from the Met Office’s global seasonal forecast system called GloSea5. Due to recent model upgrades the system now offers remarkably improved predictability of winter conditions over Europe.

The Met Office may be at the dawn of the development of a new seasonal forecast tool for offshore operators. Such a forecast tool will require serious testing and demonstration with the marine industry to determine its value.

Would seasonal forecasts help the logistics planning of tanker operations in the winter, West of Shetland? Let’s be realistic too – how good are seasonal forecasts? What type of information and what level of skill and interpretation is needed to make them useful?

Clearly we should strive to harness the potential of any benefits that seasonal forecasts can bring the marine community.

John Mitchell is a metocean scientist at the Met Office

Follow @metofficemarine on Twitter

Recommended for you