© Shutterstock / petrmalinak

© Shutterstock / petrmalinak Global energy companies are shifting to ESG investing; but what role can hydrogen play in the new energy economy? In this new series focusing on environmental, social and governance (ESG) investing in the energy industry, Mike Scott takes the temperature of the industry’s response to date, as well as the challenges ahead that this shift will present.

There are few fields where the world is changing quite so rapidly as the hydrogen economy.

Hydrogen gas has become all things to all people, in part because of its versatility as a potential sustainable energy source for transport from cars to rockets, as well as heat, electricity, and hard-to-abate industries such as steel, glassmaking and cement. On top of that, Hydrogen energy could be the solution for long-term energy storage – and it has none of the pollutants associated with other fuels at the point of use.

What is hydrogen energy?

Hydrogen energy can be produced cleanly, either as blue hydrogen (capturing carbon when stripping hydrogen from methane) or green hydrogen, which uses renewable energy and an electrolyser to split water into hydrogen and oxygen.

“Nearly everything has doubled already this year in the world of clean hydrogen, and we expect the momentum to continue in the months ahead,” says Martin Tengler, lead hydrogen analyst at BloombergNEF. More than 40 countries have now published a hydrogen strategy or are developing one.

What is the UK’s hydrogen energy roadmap towards a new hydrogen investment economy?

The UK has plans for 5GW a year of low-carbon hydrogen production capacity by 2030, from virtually nothing today, as well as a £240m net zero hydrogen investment fund and a scheme to have 20% hydrogen blending in the gas network.

And while the UK’s strategy is fairly neutral as to the balance between blue and green hydrogen, the EU, which aims to have 40GW of capacity by 2030, is much more focused on green hydrogen. By 2050, the bloc envisages €470bn (£400bn) of public and private investment in the sector.

The Hydrogen Council reports that 359 large-scale projects have been announced globally, 131 of those in the first half of 2021 alone. Europe is leading the way with investments of $130bn, but other regions are catching up. Electricity generators have almost doubled their planned hydrogen-fired turbine capacity since January, Tengler adds.

Norwegian renewable energy powerhouse Statkraft, in its latest Low Emissions Scenario, says that emissions-free hydrogen could account for 6% of global energy demand by 2050, including 7% of energy use in industry and up to 2% in buildings. BP, however, predicts that it could account for as much as 16%, if net zero targets are to be achieved.

Steam Methane Reforming (SMR)

However, it’s easy to forget that virtually all of the 70m tonnes of hydrogen produced today uses steam methane reforming (SMR) and produces more than 10 tonnes of carbon dioxide for every tonne of hydrogen. Addressing this must be the focus of initial efforts to produce clean hydrogen, both to decarbonise a sector responsible for 2% of global emissions and to create a market for the clean alternative.

Clean hydrogen energy

Behind the hype, there are a few reasons for caution.

Firstly, there is a perception that BNEF founder Michael Liebreich calls “the Swiss Army Knife of the future global economy,” where hydrogen is able “pretty much any job that needs doing.” But just because something could be done with clean hydrogen doesn’t mean it should, he says.

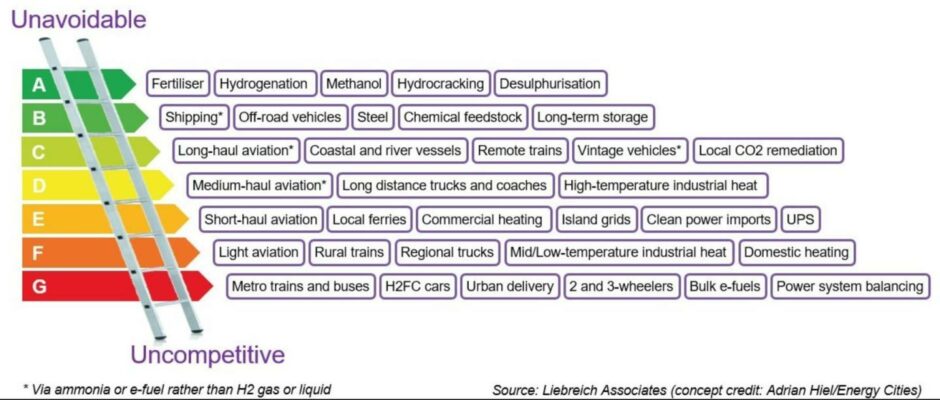

Liebreich has developed a “Clean Hydrogen Ladder”, showing which applications hydrogen is most likely to be suitable for.

At the top are fertiliser, methanol, hydrogenation and desulphurisation – in other words, the things that grey hydrogen does now. Promising new applications are in shipping, steel, long-term energy storage and chemical feedstocks.

At the bottom are many uses that have been widely touted by heavy industry, energy companies and governments, such as cars, trains and buses, as well as domestic heating.

Regardless of application, there is already appetite. In 2020, hydrogen production was already a $120bn market; Grandview Research says this will grow to $184bn by 2028. As a result, money is flooding into the sector.

For example, JCB heir Jo Bamford has launched HYCAP, a £1bn fund to invest in hydrogen production and supply. Bamford, who also owns hydrogen bus maker Wrightbus, said his team had already identified more than 40 firms to evaluate for investment.

French investment house Ardian and FiveT Hydrogen have created Hy24, “the world’s largest investment platform focused on clean hydrogen infrastructure,” which aims to raise an initial €1.5bn. Backers include TotalEnergies, Air Liquide and Vinci.

Meanwhile, HydrogenOne Capital Growth, backed by Ineos, is aiming to raise £250m on the London Stock Exchange. The fund has made its first equity investment, providing £20m to Germany’s Sunfire, a builder of electrolysers.

Meanwhile, energy generator and retailer Octopus is joining forces with renewable energy developer RES to invest £3bn in green hydrogen production by 2030.

Blue hydrogen development projects

European energy majors are also investing in sustainable energy solutions.

Shell recently commissioned what is, for now, Europe’s largest PEM electrolyser at 10MW, in Germany, initially to cut emissions from its refinery operations. By 2023, it is planning to build a 200MW electrolyser at the Port of Rotterdam, as part of the Rotterdam Green Hydrogen hub.

It is also involved in NortH2, a project that could produce more than 800,000 tonnes of hydrogen from a 10GW offshore wind farm in the North Sea, with partners including Gasunie, RWE and Equinor.

Equinor and Engie are working on blue hydrogen projects in Belgium, the Netherlands and France, including a plan to convert part of a gas-fired power station in the Netherlands to run on hydrogen, as well as H2morrow, a project to generate and transport blue hydrogen to Germany’s largest steelworks in Duisburg.

Ineos has recently announced plans to spend more than £3bn to develop green hydrogen across Europe, building electrolysers in Germany and Norway, as well as upgrading its Grangemouth refinery to run on hydrogen.

BP is planning to build the UK’s largest hydrogen plant, a blue hydrogen facility on Teesside, while much of TotalEnergies focus involves mobility, with almost 30 hydrogen refuelling stations in operation across Western Europe, principally to service trucks and buses.

Yet, while blue hydrogen fits more easily into oil and gas companies’ existing operations, it relies on carbon capture and storage (CCS), development of which has been painfully slow, as well as pipelines and storage facilities that are yet to be developed.

Increased development of Electrolysers and Green Hydrogen

By contrast, the pace of development of green hydrogen infrastructure is extremely rapid.

While total global capacity of electrolysers was less than 200MW in 2020, that is set to double in 2021 and quadruple in 2022. By 2030, cumulative global electrolysers installations could exceed 40GW.

Expansion at that pace will see the cost of the technology plummet at the same time as the cost of renewable energy continues to fall. BNEF says green hydrogen will be 85% cheaper by 2050.

“By 2030, it will make little economic sense to build blue hydrogen production facilities in most countries, unless space constraints are an issue for renewables,” says Tengler. “Companies currently banking on producing hydrogen from fossil fuels with CCS will have at most ten years before they feel the pinch. Eventually those assets will be undercut, like what is happening with coal in the power sector today.”

With the International Energy Agency’s World Energy Outlook and COP26 setting the scene for a much quicker energy transition than many anticipate, blue hydrogen runs the risk of being left behind before it even gets started.