Firms won’t be rushing into deals or investment off the back of higher oil and gas prices – the boom may even be stalling such activity in the North Sea, according to top analysts.

Brent crude has surged in recent weeks, going beyond $100 in February for the first time since 2014, and even reaching beyond $130 in the wake of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

But North Sea operators are expected to keep a cool head when it comes to investment.

Yvonne Telford, senior analyst at Westwood Global Energy Group, says that, with prices now higher, this will initially help reverse write-downs and reduce debt positions.

However, there remains “considerable uncertainty” on the political environment and price, so some firms are “unlikely to rush into making substantial increases to 2022 budgets or make M&A deals.”

Exactly when and at what level prices will stabilise remains an unknown, she adds.

That volatility could even be “stalling transactions and corporate decision making”, according to Andrew Reid, partner at NorthStone Advisors.

He said: “It’s exceptionally difficult to plan around extreme uncertainty and, as such, we will likely see assets that were due to come to the market being delayed while buyers also pause.”

Both agree that an uplift in longer-term investment opportunities, such as large new greenfield developments or exploration and appraisal activity will depend on mid-term price forecasts.

“Investment decisions are not made on the short-term outlook or spot prices, this is why it’s still important to the long-term pricing assumptions for oil as this is what will drive activity and valuations”, says Reid.

The Energy Information Administration (EIA) in the US expects to see a drop of around 15% in the average price of Brent Crude in 2023 to $89 a barrel, down from $105 this year.

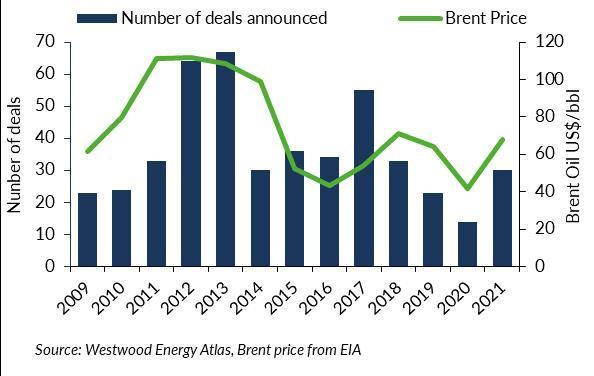

Could M&A and investment pick up as a result of the oil price surge? History tells us that in early 2011, the Brent spot price rose above $100 per barrel and remained at that level until September 2014.

However M&A didn’t pick up materially until 2012, as activity in 2011 was only marginally higher than 2010.

“Buyers needed stability in price before embarking on high value purchases”, Telford notes.

Thereafter, new projects and investment did pick up significantly – bringing with it higher costs which meant the downturn of 2014 was felt particularly hard.

Telford adds: “With this history in mind, and the price crash and enforced cost management which ensued after this ‘golden’ period, companies are likely to remain more cautious on project costs and future activity levels.”

From an M&A perspective, there has been an “increasing disconnect” between buyer and seller expectation in certain regions, argues Dave Moseley, VP of North Sea Research at Welligence, but this has yet to materialise in the UK sector.

“This is perhaps at least partially due to a pro-active regulator that has facilitated deals through initiatives such as the Transferable Tax History launched in 2018,” he says.

“However, if commodity prices remain inflated through 2022 there is likely to be an impact on future levels of M&A.

“Deals may only cross the line if more novel terms can be agreed, such as reduced upfront considerations in favour of trigger events for contingent or staged payments to reflect the more uncertain and volatile near-term outlook.”

Moseley adds that higher commodity prices will see corporate loss positions reduced, which have historically been a catalyst for many transactions where buyer-seller tax synergies were key.

Telford of Westwood also notes that buyer and seller expectations can vary during times of volatility, which is why stability is key for M&A.

“High prices are likely to create more potential buyers and the longer the oil price remains elevated and stable the more confident companies are to complete deals.

“The UK has a high number of acquisition opportunities, from E&A farm-ins and unfunded development opportunities through to producing assets.

“The limitation in the UK has been the size of the prospective buyer pool and what buyers classify as quality acquisition targets. Buyer and seller value expectations can also be wider in periods of price volatility, and although energy security is reversing the investor sentiment of late 2021.

“Westwood expects deal activity to be steady rather than record-breaking.”

Reid, of NorthStone, notes that exploration and production firms are not under pressure for growth and are moving more to a “yield” focus, with returning value to shareholders through dividends, buybacks or reducing debt the name of the game.

“Any investment will likely focus on fast payback initiatives, from well intervention or marginal field tiebacks,” he adds.

Along with the soaring oil price, recent weeks have also brought what John Corr, head of North Sea at Welligence, describes as a “shift in favour of indigenous oil and gas” despite increasing pressures from the environmental lobby.

“Current events have provided a potentially needed shock, as the reality of the challenge to achieve net zero whilst maintaining energy security has been driven home.”

This “shock”, just months after the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow, has coincided with some high-profile North Sea projects going back into vogue, but political support for the sector isn’t air-tight.

Reid says: “As we have noted, the commodity price increase has been highly volatile and remains uncertain, while political sentiment for the sector is equally confused and fiscal threats remain.”

A windfall tax did not materialise in the Chancellor’s Spring Statement, but continued strong support may be needed to bring about large new projects going forward, Corr of Welligence notes.

“With commitment by the UK Government to oil and gas seemingly in a state of flux, there could be some hesitancy by companies to invest in large projects with long payback periods in the current environment.”

© Supplied by AJL

© Supplied by AJL