© Bloomberg

© Bloomberg Climate negotiators at COP28 may bolster carbon trading when they decide on rules for a new United Nations-overseen emissions market that can lower the cost of fighting global warming.

In Dubai, envoys representing more than 190 nations are set to discuss standards for credits that allow their holders to compensate for pollution at home by investing in projects elsewhere to cut emissions or remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. The UN-sponsored program aims to ensure high quality credits within an internationally agreed framework, offering investors greater certainty amid concerns that some existing voluntary projects do little or nothing to curb climate change.

“At COP28, regulators can help create demand by embracing acceptable quality standards that give voluntary buyers confidence,” said Benedikt von Butler, portfolio manager at Evolution Environmental Asset Management LP.

The idea of using cross-border carbon markets to accelerate the green transition is nothing new. The Kyoto Protocol in 1997 paved the way for the Clean Development Mechanism: a program once worth $8.2 billion per year that boosted aid flows to emerging countries needing help in curtailing emissions.

It allowed developed countries to use credits generated by cheaper greenhouse gas-cutting projects in developing nations to meet part of their pollution-reduction targets under the Kyoto treaty. After about six years of operation, prices collapsed close to zero in 2012 on concerns about the integrity of the projects and the European Union’s decision to limit the use of CDM credits for compliance in its domestic market.

The concept got a fresh boost from the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement: under Article 6, nations agreed to work toward a new global system of exchanging allowances covering greenhouse gases. In the following years, envoys worked on designing a robust financial instrument that would translate national emissions-reduction pledges into comparable, exchangeable units.

Holy grail

“A successful and timely implementation of Article 6, often heralded as the Holy Grail of international cooperation in climate change, is seen as critical to the future of carbon pricing,” said Robert Jeszke, head of the Centre for Climate and Energy Analyses think-tank in Warsaw.

The framework needs to be flexible enough to attract investment, while also credible enough to avoid the issues that sank the CDM. Some investors hope that a strong framework could open the door for carbon credits under the new UN program to be accepted in national or regional compliance markets across the world, such as the EU Emissions Trading System.

The UN market will include a project-based mechanism, where companies can offset some residual emissions and reach voluntary net-zero climate goals by buying credits from registered pollution-reduction initiatives. The platform may attract investors currently relying on voluntary markets and serve as a model for initiatives that follow varying standards and governance frameworks.

Way forward

Earlier this month, the new market’s supervisory body reached a deal on key technical rules to make the so-called Article 6.4 mechanism operational. The challenge now is for countries at COP28 to overcome remaining divisions and approve those recommendations in Dubai.

“We were able to find a way forward that allows us to deliver on our mandate and sets out a work programme to continue improving and expanding the framework for the Paris Agreement crediting mechanism,” the supervisory body’s chair Olga Gassan-zade said in a statement on Nov. 18.

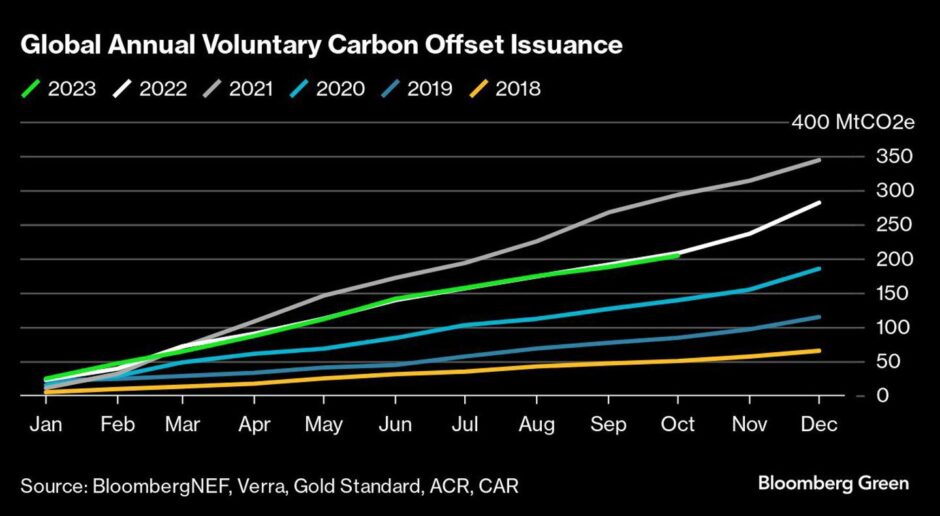

Voluntary carbon credit projects attracted $36 billion of investment between 2012 and 2022, according to data by Trove Research, which was recently acquired by MSCI. It estimates that a further $90 billion of project investment will be needed to deliver the volume of credits required this decade to avoid exceeding the critical 1.5C warming limit.

“We now hope the agreement will be adopted at COP28, so further technical work can kick off next year and the first credits can be issued towards the end of 2024,” said Andrea Bonzanni, international policy director at the IETA association, promoting carbon markets. “Without this agreement, everything would have been pushed back to 2025.”