© Supplied by Technip Energies

© Supplied by Technip Energies Brexit was followed by the UK’s exit from the EU Emissions Trading System (ETS) and the establishment of a UK ETS from 1 January 2021, creating different carbon prices for industry in the EU and the UK. However, the UK’s approach to carbon pricing has always been a little different to the EU.

In its early years, the EU ETS failed to produce a carbon price of any great significance to the energy transition. In other words, carbon was priced too low to incentivise investment in decarbonisation. This period lasted until 2020 when reforms were introduced, which effectively addressed the EU ETS’ excess supply of carbon allowances.

The surplus was caused by a combination of poor system design and the need for a soft initial impact to sustain stakeholder buy-in and acceptance of the additional costs the system imposed. Post reform, the annual reduction of allowances and need for industrials to buy a rising share of their allowances suggest a long-term upward price trend that incentivises decarbonisation.

Carbon Price Floor

Recognising the limited impact of the early phases of the EU ETS, the UK acted unilaterally, introducing a carbon price floor (CPF) from April 2013 of £15.70/mt CO2. This was charged on top of the EU ETS price and subsequently on top of the UK ETS price. Originally intended to rise by about £2 a year, the then government’s environmental chutzpah faltered and it capped the CPF at £18/mt CO2 in 2016.

Paradoxically, the post-Brexit creation of the UK ETS came at a time when the EU ETS had finally been fixed. The two systems initially traded fairly close together, but from the start of 2023 they diverged, reflecting a UK government decision to increase the supply of carbon allowances. The situation was fully reversed, the UK replacing a fixed system with one it promptly broke.

The price difference widened in the summer of 2023 with the UK ETS falling faster than the EU ETS, meaning that UK buyers of carbon allowances were paying less than their EU counterparts even with the CPF included.

As of 7 October, UK carbon prices were trading at £35.29/mt CO2 versus an EU ETS price of £51.65. Add on the CPF, and the price of carbon in the UK was slightly higher than in the EU at £53.29, leaving a large gap between traded carbon allowance prices, but a relatively small difference in terms of the full cost.

Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM)

The EU’s introduction of a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) has heightened the sensitivity of different carbon prices in the two jurisdictions. CBAM aims to level the carbon cost applied to domestic EU products and imports to stop carbon leakage – the relocation of industry to jurisdictions with lower carbon costs. As a result, EU importers of UK goods could face a penalty to align the carbon cost of UK imports with the EU ETS.

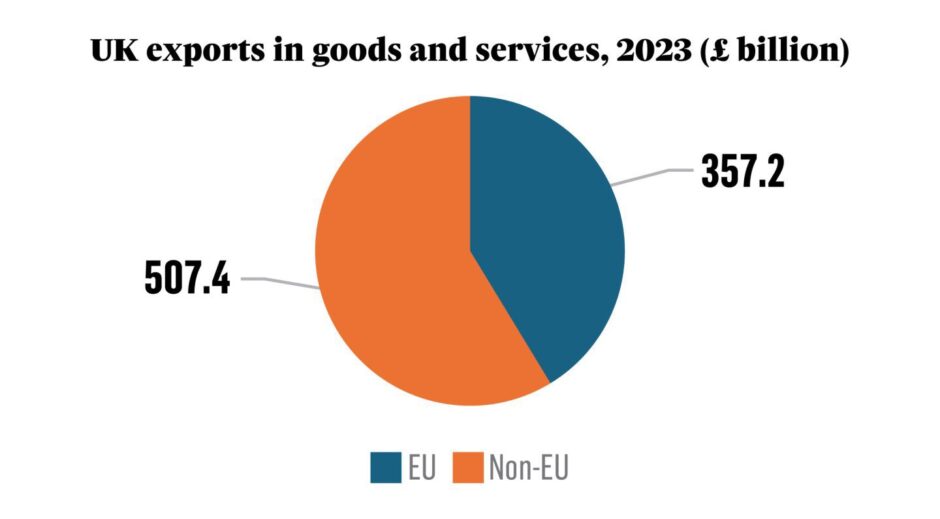

Last year, 42% of UK exports went to the EU, including 49% of goods, so the impact could be significant. The liability created by CBAM falls on the EU importer of the goods not the UK producer. EU importers may absorb some of the cost, but may also push back on UK producers to reduce prices or choose different suppliers.

How the price paid by an importing country is calculated is to be decided before the end of 2025, the end of CBAM’s transitional phase. It is likely, but not certain, that the full cost of carbon in the UK – the UK ETS plus CPF – will be taken into account. Nonetheless, UK producers will still face a price differential of some sort and significant compliance burdens.

The UK has also proposed a CBAM to prevent carbon leakage and allay concern that it might become a destination for high carbon imports shunned by EU importers. As with the UK ETS, the UK CBAM will have differences from the EU one. Its current envisaged form was inherited from the former Conservative government; it starts a year later, covers slightly different sectors, has no transitional period, and a different mechanism for setting prices.

Carbon content is the key issue

The debate has tended to focus on whether UK exports to the EU will face additional costs and therefore lose attractiveness in the EU’s single market. A more fundamental issue is ignored. The price paid on imports to the EU depends not simply on the price of the EU ETS, but on the carbon content of the goods produced. Produce low carbon goods and an exporter to the EU will not suffer high costs under CBAM, whether based in the UK or elsewhere.

According to Rabobank, the UK’s production of cement, aluminium and iron and steel products is on average more carbon intensive than the EU average. These exporters will be less competitive in the EU single market not because of CBAM per se, but because of the carbon intensity of their production. UK fertiliser production, in contrast, is less carbon intensive on average than in the EU, so this sector may still face higher carbon costs, but remain competitive, and could become more so relative to other higher carbon content producers importing into the EU.

The EU’s CBAM is non-discriminatory except with regard to embedded carbon, which it penalises. Assuming, for a second, that all other costs are equal, UK goods will be attractive in the EU, if they are lower carbon than their EU counterparts and/or they are lower carbon than those of competing exporters to the EU. The way to improve competitiveness is to reduce the carbon intensity of the products produced, which is, of course, the whole point of the exercise.

Carbon competition

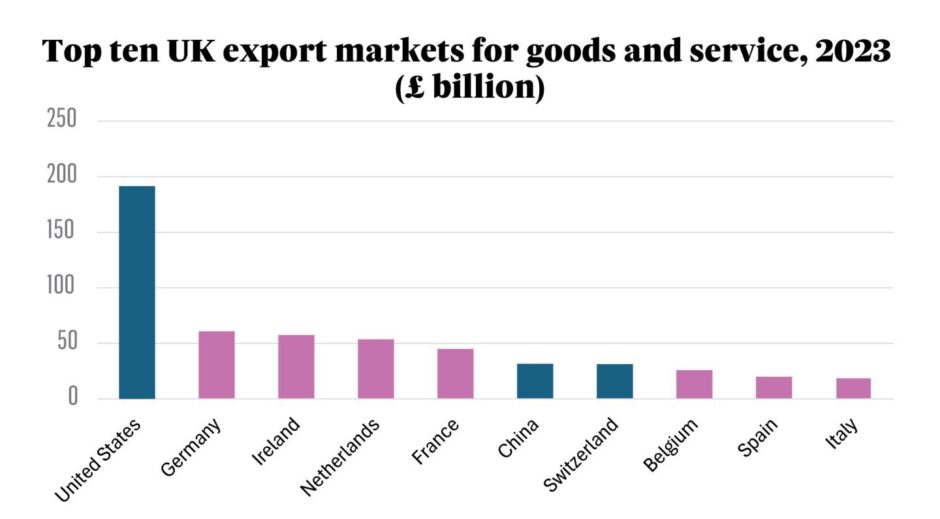

Lower UK carbon costs will be levelled up by the EU CBAM for exports to the EU, but a lower UK carbon cost would still benefit UK producers exporting to markets other than the EU – 51% of exported goods – and would create less of a carbon cost domestically. It could help make UK goods more competitive versus their EU competitors in non-EU markets.

This would have a feedback effect on the attractiveness of exporting to the EU and the UK’s trade might reorientate more towards non-EU markets. This is a form of carbon price competition.

The UK’s intention to introduce its own CBAM suggests that this is not its aim. Moreover, a harmonised CBAM-protected bloc would be more effective in levelling carbon costs and encouraging external decarbonisation than one in which governments design their CBAM and ETS systems differently. The latter inevitably leads to different carbon prices and one or the other gaining advantage in export markets, creating carbon price competition, whether it is a policy intention or not.

An associated impact is that the system which delivers lower prices raises less revenue for the energy transition. The combination of economic advantage from low carbon prices and less impetus towards decarbonisation appears misaligned with the UK’s stated ambition of net zero by 2050.

The sheer complexity of the inter-operation of the UK and EU ETSs when both have CBAMs, and the reporting requirements they impose, are also legitimate concerns. This creates real costs for business over and above the respective carbon prices. It is a potent practical argument for harmonisation.

Loved or not, the UK ETS is Brexit’s child

Harmonisation would pull the UK more closely back into the orbit of the EU’s single market because it would mean in practice, if not in name, rejoining the EU ETS, which is much bigger.

This would involve the swallowing of some Brexit pride to achieve a more effective all-Europe response to climate change. And it would likely consolidate trade with the EU, as opposed to maintaining separate systems and a degree of carbon price competition, which in turn creates incentives for trading with non-EU countries with less or no carbon pricing requirements.

This underlines just how much the UK ETS is the offspring of Brexit. The UK ETS cannot rid itself of Brexit’s DNA.

It also highlights how trade and environmental policy are increasingly inseparable. In attempting to derive economic advantage from a separate UK ETS and achieve its stated environmental goals, the UK would be pulling itself simultaneously in opposite directions. It appears that both harmonisation and pursuing a sole path to a common goal create a price that must be paid – albeit in different ways.

Ross McCracken is a freelance energy analyst with more than 25 years experience, ranging from oil price assessment with S&P Global to coverage of the LNG market and the emergence of disruptive energy transition technologies.