The bear market in oil has analysts reassessing the U.S. shale boom after five years of historic growth.

The U.S. benchmark price dropped to $79.78 a barrel on Oct. 16, the lowest since June 2012. At that level, one-third of U.S. shale oil production would be uneconomic, analysts for New York- based Sanford C. Bernstein & Co. led by Bob Brackett said in a report yesterday. Drillers would add fewer barrels to domestic output than the previous year for the first time since 2010, according to Macquarie Group Ltd., ITG Investment Research and PKVerleger LLC.

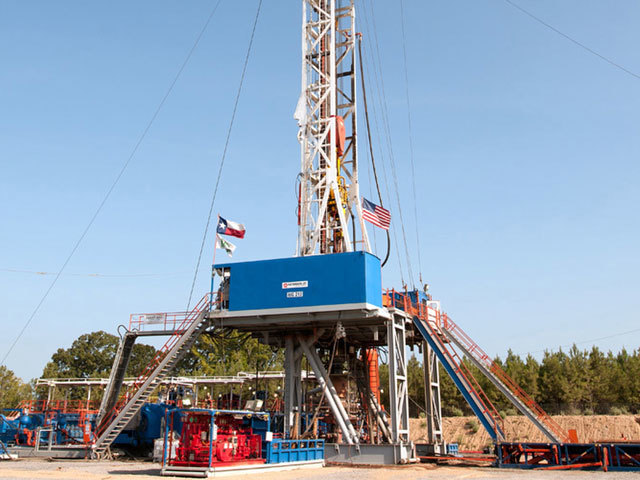

Horizontal drilling through shale accounts for as much as 55 percent of U.S. production and just about all the growth, according to Bloomberg Intelligence. The Paris-based International Energy Agency predicted in November that the U.S. would pass Russia and Saudi Arabia to become the biggest producer in the world by 2015. Though some forecasts show oil rebounding or stabilizing, any slower increase in U.S. output would shake perceptions for the global market, said Vikas Dwivedi, an oil and gas economist in Houston for Sydney-based Macquarie.

“It would reshape the way everybody would think about oil,” Dwivedi said.

Daily domestic production added a record 944,000 barrels last year and reached a 29-year high of 8.95 million barrels this month, according to the Energy Information Administration, the U.S. Department of Energy’s statistical arm.

Output, much less growth, is difficult to maintain because shale wells deplete faster than conventional production. Oil production from shale drilling, which bores horizontally through hard rock, declines more than 80 percent in four years, more than three times faster than conventional, vertical wells, according to the IEA. New wells have to generate about 1.8 million barrels a day each year to keep production steady, Dwivedi said.

At $80 a barrel, output would grow by 5 percent, down from a previous forecast of 12 percent, according to New York-based ITG.

At $75 a barrel, growth would fall 56 percent to about 500,000 barrels a day, Dwivedi said. Closer to $70 a barrel, the growth rate would drop to zero, he said.

In North Dakota’s Bakken shale, oil at $70 a barrel could cut production 28 percent to 800,000 barrels a day by February from the 1.1 million barrels a day that was pumped in July, according to Philip Verleger, who was an economic adviser to President Gerald Ford and the director of the Office of Energy Policy for President Jimmy Carter.

“The cash flow will go down as the prices go down, the amount of money advanced to these people to continue the drilling will dry up entirely, so you’ll see a marked slowdown in drilling,” said Verleger, who runs PKVerleger in Carbondale, Colorado, referring to the industry as a whole.

West Texas Intermediate crude, the U.S. benchmark price, has fallen 23 percent since June 20.

The price will rise to a level where more output is economic, the Sanford C. Bernstein analysts said. The flood of oil from shale is powerful enough to put a ceiling of $90 a barrel on prices through the latter half of this decade, and at times the price will dip to as low as $70, Eric Lee, an oil market strategist at New York-based Citigroup Inc., said yesterday in a phone interview.

There’s a risk the price will “briefly” fall to $75 a barrel before global demand recovers in 2015, Bank of America Corp. analysts said last week. They predicted an average price of $85 a barrel in the fourth quarter.

Investors are more bearish. They’re holding the highest number of short positions on WTI in 22 months, U.S. Commodity Futures Trading Commission data show.

The impact of the bear market on supply could be muted depending on how many companies locked in higher prices with derivatives contracts, Verleger said.

Shale drillers managed to keep expanding production of natural gas even after prices collapsed, said Amy Myers Jaffe, executive director of energy and sustainability at the University of California-Davis. U.S. output rose 3.8 percent to 2.6 trillion cubic feet a month in the year to July, EIA data show, even as the rig count fell in April to a 21-year low, according to data from Baker Hughes Inc., a Houston-based oilfield-services company.

Drillers could also maintain output by improving efficiency. Each rig in the Permian Basin of West Texas will add a record 176 barrels of new oil a day in November, up 20 percent from a year previous, according to an EIA estimate. In the Eagle Ford, each rig is getting 540 new barrels a day, also up 20 percent.

The cost of completing a well in the Leonard shale of the Permian’s Delaware Basin fell to $5 million this year, compared with $6.9 million in 2011, according to Houston-based EOG Resources Inc.

Companies could also drill wells closer together, called downspacing. The practice is relatively new in horizontal drilling, and there’s a risk neighboring wells will interfere with one another. So far, production results have been mixed.

“The companies that got in early and have low costs and already built the infrastructure are going to continue to execute on their strategies,” said Bill Kroger, Houston-based co-chair of the energy litigation practice at Baker Botts LLP. “If prices stay down for the long term it’s possible we’ll see production fall off but I don’t think we’re there yet.”

While analysts have focused on the price at which shale drilling remains economic, companies that can profit at $80 a barrel may still curb their budgets as returns shrink, said Shane Fildes, the Calgary-based head of global energy at BMO Capital Markets.

“You’ll see a supply response more quickly than some people expect,” Paul Sankey, an analyst with New York-based Wolfe Research LLC, said Oct. 17 in a note to clients. “While it could take several months to see a clear supply impact, we do expect to see a drop in completed wells in the major basins within a couple of months.”

Recommended for you