Last month, the total US drilling rig count fell to a record low since Baker Hughes began tracking the data in 1949.

However, one eagle eye has calculated that, even by adjusting the current record low rig count of 480 upwards by a liberal 30% to cover drilling efficiency gains, it would still be lower than just about any other time in recorded US drilling history.

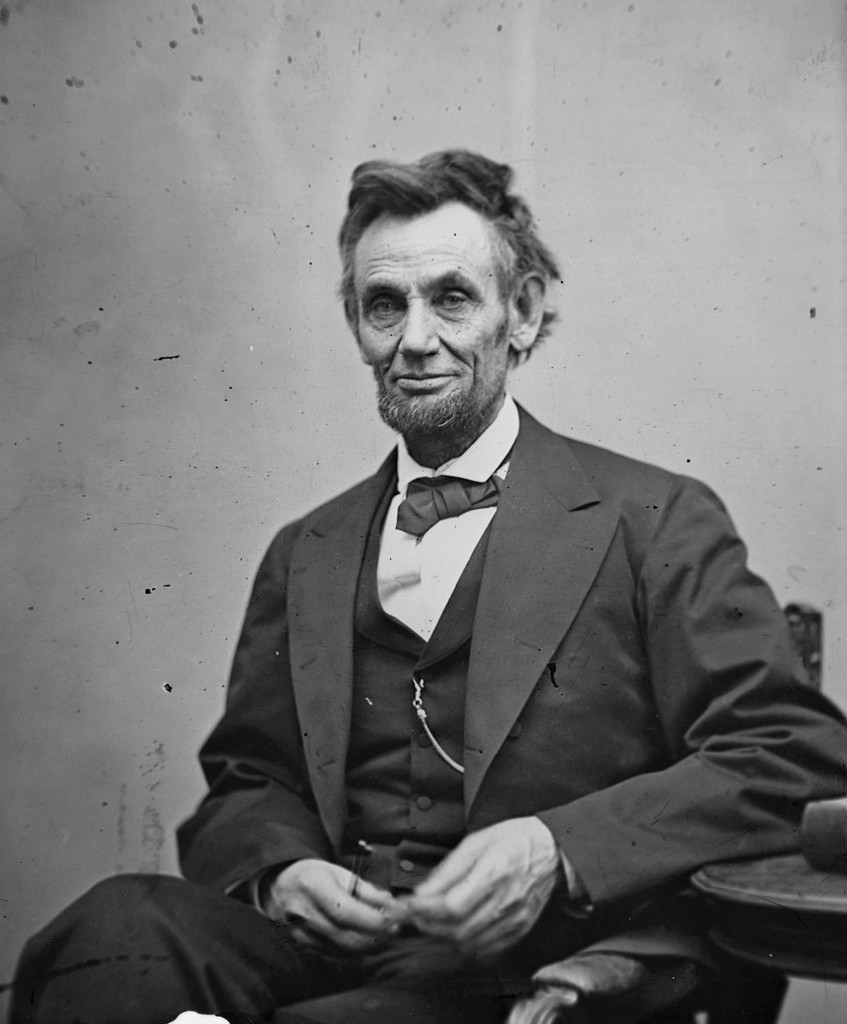

In fact, Joseph Triepke of Oilpro reckons the last time the rig count was this low was when Abraham Lincoln was president of the United States of America.

“A rig drilling today is not the same as a rig drilling 100, 50 or even 10 years ago,” writes Triepke in a commentary.

“Leaps in modern drilling rig efficiency and productivity (as well as capital intensity) is something we’ve written about repeatedly over the past several years.

“But the one constant in our industry’s modern history is that everything starts with a rig drilling a hole in the earth.

“A long uninterrupted data-set makes rig counts useful context even though rigs are now less relevant to production than completions.

“Although we don’t have consistent records of active rig counts prior to 1949, we believe the total US drilling rig count hasn’t been this low since the inception of the modern US oil industry – about the same time that Abraham Lincoln was sworn in as the 16th US president.”

That was in 1861, just two years after Edwin Drake famously used a basic wood-framed derrick to drill the first successful oil well in north-west Pennsylvania State.

His success marked the beginning of the oil drilling industry, and the number of active drilling rigs grew quickly, turning the Appalachian Basin into a leading oil producer (supplying half the world’s oil).

Triepke: “By the time Abraham Lincoln was inaugurated as US president in 1861, the US rig count (albeit comprised of wooden derricks, not the highly engineered steel of today) was very likely either at or above today’s levels and climbing.

“We believe that no other downturn since the modern US drilling industry began has taken the US drilling rig count as low as current levels. Doing more with less (ie technology) plays a role, but so too does the worst downturn in the industry’s history.”

Also on the wells front, this time shale wells, various pundits and industry alumni have been trying to work out just how many “DUCs” . . . drilled but uncompleted wells . . . have been drilled since the oil price crashed more than 18 months ago.

According to Tom Kirkman, a poster on the Oilpro board, it seems that so far, no one has been able to successfully track the actual number of DUCs in the US, and whether the number of DUCs is increasing or decreasing.

Bloomberg Intelligence has been attempting to track the number of DUCs, but so far appears unsuccessful. EIA estimates anywhere from 2,000 to 4,000 DUCs.

But it seems that just how many have in reality been drilled is anybody’s guess.

Kirkman says: “Seems to me that if a fairly accurate number of DUCs can be established, and then tracked whether that number is increasing or decreasing, the results may provide a clue as to how the eventual recovery from oil oversupply is progressing.

“The global oil & gas industry has to deal somehow with the current global excess oil production, and eventually pare down the amount of crude stored.

“The US in particular has to deal with DUCs eventually being completed, which will add to oil & gas production.

“The first step would seem to be nailing down a fairly accurate number of DUCs from 2015, and then move forward from that number for comparison. I’m open for suggestions how to actually do this.”

In a nutshell, no one really knows and this appears to reveal a weakness in the way the US authorities are managing the shale effort.

The presumption is that, by having drilled thousands of DUCs at bargain rig rates, US producers can take rapid advantage of any small up-lift in commodity prices and make money, but also perhaps swiftly dampen the market.

Recommended for you