Europe’s biggest oil companies, reeling from losing billions in the two-year oil market rout, are intensifying their push into renewable energy as they hunt for new sources of future revenue.

Shell, Eni, Total and Statoil have announced green energy investments with a combined value of around $2.5 billion in recent weeks in a bid to diversify away from their core oil and gas markets.

French oil major Total, which has said it wants to become a “leader” in renewables and electricity storage within the next 20 years, has so far made the biggest commitments among its European peers in green energy. Last week, it spent $1.1 billion to acquire energy storage maker Saft. It has also held a majority stake in solar panel manufacturer SunPower since 2011.

The deals are part of Total’s stated ambition and to help to drive this, it will appoint an executive board member to lead its new gas, renewables and power division from Sept. 1.

“People innovate when they are against the wall,” the chief executive of French oil major Total, Patrick Pouyanne, told reporters this week.

“You need to innovate, otherwise when you stick to your position you just cannot create money.”

Shell, Europe’s biggest oil company, is also setting up a dedicated ‘new energies’ unit that will incorporate its wind and solar as well as hydrogen and biofuel investments, an internal memo seen by Reuters showed.

BP recently raised its forecast for global green power generation by 2035 to 15 percent.

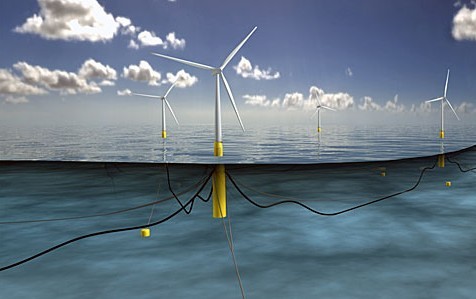

Statoil recently gave the green light to its Hywind project off the coast of Peterhead, near Aberdeen and investing $200m in its Energy Ventures subsidiary.

Dong Energy has announced plans to use the income from its fossil fuel business to fund investment in renewables.

However, the rush to invest in renewable energy is unlikely to directly replace the value from untapped reserves.

“These companies have trillions of dollars of oil reserves on their books,” said Ben Warren, head of energy and environmental finance at consultancy E&Y.

“But in ten years from now, if solar energy continues down its cost curve and battery technology means we can transport energy wherever we need it, are those reserves ever going to get extracted?”

So far, the commitments to the sector remain small. Shell’s pledge of $200 million for its new energies activities is less than one percent of the company’s $30 billion annual capital expenditure program.

“At the moment the investments in renewables by big oil is small, relative to their total capital employed and given the early stages they do not tend to generate significant returns,” said Rohan Murphy, co-manager of the Allianz Global Energy Fund, which invests in oil majors like Shell and Total.

Tom Ellacott, senior analyst at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie, said through renewable energy investments oil majors will have to get used to utility-type returns.

These are typically in the single to low double digits.

This, as well as some past experiences, have made companies cautious about significant investments in renewables. BP, for instance, closed its solar power unit in 2011 after it could not withstand harsh competition from Chinese manufacturers, overcapacity and tumbling prices.

Despite such reservations, many investors are still keen to see oil majors reduce climate-harming carbon emissions from their asset base on the back of a global climate agreement to curb emissions struck in Paris last year.

Institutional investors including pension funds, infrastructure funds and sovereign wealth funds will be able to respond to clients’ growing requests for more socially conscious investments, they say.

“As a fund we’ve been under pressure from investors who don’t care whether renewables makes money,” said Richard Hulf, co-manager of the Artemis Global Energy Fund, which holds shares in major oil companies including Shell and Total.

Recommended for you