It wasn’t a normal business trip, even for Ian Taylor. Over an almost 40-year career in oil, the Oxford-educated Brit had set down in plenty of hot spots, from Tehran to Caracas, Baghdad to Lagos. Yet this journey—destination Benghazi, Libya, in the midst of a civil war—was different.

All Taylor had to do was peer out the window of the private plane he was in for a reminder. A thousand feet below, a NATO drone chaperoned the aircraft. Taylor, the compactly built chief executive officer of Vitol Group, the world’s biggest independent oil trader, found himself wishing it were a proper fighter jet.

It was early 2011. Forces revolting against the 42-year dictatorship of Colonel Muammar Qaddafi had just taken control of the city and founded their own government. This meeting with the ragtag group of former military officials and local politicians had come together quickly, but if anybody could arrange something with them, Taylor figured, it was Vitol. A few weeks earlier, one of his top executives, Christopher Bake, had fielded a call from Doha. Qatar’s oil minister, an intermediary explained, wanted to know if Vitol would be willing to supply fuel to the Qatari-backed Libyan rebels. Vitol had just four hours to reply.

Bake, based in Dubai, signaled Vitol’s interest “in about four minutes.” He then looped in his colleagues, most of them in London, to pull together a firm proposal. Vitol, he soon told the intermediary, was in. That they could move on a deal like this—in a bloody war zone—spoke volumes about the company’s culture. As anybody in the oil business could attest, Vitol was a nimble and hungry opportunist, always ready to pounce.

Now, inside the plane, Taylor and Bake, who looks almost like a bodyguard thanks to his rugby-player frame, were en route to clinch the deal. But there was a catch: The rebels had no money. Vitol would have to be paid in crude. Western governments tacitly approved the arrangement, although aside from the lone drone, there wasn’t any official support. If something went wrong, Taylor and his company were on their own.

The two men braced themselves as the plane banked hard. The risk of anti-aircraft fire from Qaddafi forces made a conventional landing impossible, so the pilot descended rapidly in a series of stomach-churning turns. Once on the ground, Taylor and Bake made their way to the designated meeting point.

Back then, the center of Benghazi, a tired collection of dusty 1970s buildings around a fetid lagoon, was a far more dangerous place than the one portrayed in this year’s Hollywood film 13 Hours: The Secret Soldiers of Benghazi, about the attack that killed U.S. Ambassador to Libya J. Christopher Stevens in September 2012. In the early days of the civil war, Benghazi was a city where nearly every man—and often even children—carried a Kalashnikov, and the rest of the population lived under the constant threat that Qaddafi troops could breach the city’s defenses.

After some discussion, Vitol accepted the deal. Things went awry within days. Despite promising to keep it secret, the rebels announced they’d made an arrangement to sell oil. In response, Qaddafi’s forces immediately blew up a key pipeline. Without oil, Vitol couldn’t be paid.

Still, the company upheld its end of the bargain. Over the coming months, its tankers shipped cargo after cargo of gasoline, diesel, and fuel oil into eastern Libya. “The fuel from Vitol was very important for the military,” Abdeljalil Mayuf, an official at rebel-controlled Arabian Gulf Oil in Benghazi, later said.

In the end, the rebels brought down Qaddafi, and once the fighting subsided, Vitol got its oil. At one point, as everyone waited for production to restart, the amount owed by the rebel government ballooned to more than $1 billion.

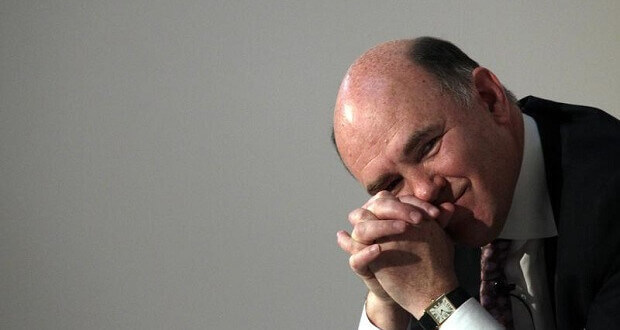

Five years later, Taylor, now 60, recalls the Benghazi affair over breakfast at London’s St. Pancras station ahead of the 9:18 a.m. Eurostar to Paris. “It was a deal which, to be honest, got much larger than it should have,” he says.

The boldness of the Benghazi deal epitomizes the world of Vitol—a high-stakes mix of business and energy geopolitics conducted in some of the most difficult corners of the world. The closely held company, which last year made a net profit of $1.6 billion, is a hidden giant of the global economy, handling more than 6 million barrels a day, enough to meet the combined daily needs of Germany, France, Italy, and Spain.

Over half a century (the company will celebrate its 50th anniversary in August) Vitol has never suffered an annual loss. Profits surged from just $22.9 million in 1995 to a record $2.28 billion in 2009, according to documents reviewed by Bloomberg Markets. At its peak, Vitol’s return on equity, a measure of profitability compared with the money that partners have invested, was a geyserlike 56 percent. Even Wall Street pales in comparison; Goldman Sachs’s best ROE since going public in 1999 is 31 percent. “Vitol has established itself as the ultimate energy trader,” says Jean-François Lambert, who as former global head of commodity and structured trade finance at HSBC dealt extensively with the company.

This is the story of how Vitol got there and how at times it stumbled along the way—reconstructed by Bloomberg Markets through two dozen interviews with current and former executives and others in the industry, and reviewing hundreds of pages of previously unreported financial and legal records filed in the Netherlands, the U.S., and Luxembourg.

Vitol, which trades about 6.5 percent of the world’s oil, fights in a tough arena. It competes with other independents such as Glencore, Trafigura Group, Mercuria Energy Group, Gunvor Group, and Castleton Commodities International. It also grapples for market share against Big Oil’s in-house trading arms, including those of BP, Royal Dutch Shell, Total, and, increasingly, state-owned Chinese oil companies.

As for the future, Vitol faces a daunting fact: The best days of oil trading are almost undoubtedly in the rearview mirror. Margins are shrinking as the market becomes ever more transparent and competitors emerge fighting for the same barrels. Even as Vitol sinks more capital into assets such as refineries and terminals, returns are falling. Last year’s ROE was 16 percent—for Vitol, a less-than-stellar number.

Taylor became an oil trader by chance. Of Scottish descent, raised and educated in England, he went to work at Shell for a simple reason: It paid better than other jobs he was considering. Starting in 1978 he learned the oil-trading ropes through stints in Singapore and Caracas, where he met his wife.

Vitol has grown like a Silicon Valley startup under Taylor, who came on in 1985 and took the top job a decade later, transforming the company into one of the world’s top traders as oil demand surged in China and other emerging markets. During his time as CEO, Vitol has increased its equity value by 3,500 percent, from $278 million in 1996 to almost $10 billion last year. Over the same period, Glencore went from $1.2 billion to $35 billion, a smaller though still impressive 2,800 percent rise.

Vitol was born amid more modest ambitions. In August 1966, two Dutchmen, Henk Viëtor and Jacques Detiger, invested 10,000 Dutch guilders (about $2,800 at the time) to start a Rotterdam company with the aim of buying and selling refined petroleum products by barge up and down the Rhine. They crunched Viëtor and “oil” to get Vitol. The money was a loan from Vietor’s father and the pair agreed to pay an annual interest rate of 8 percent. Detinger, now 81 years old, remembers that Vietor’s father told him: “You have 6 months—if it doesn’t work, you’re out.”

The company’s first accounts showed a small profit and a balance sheet of 200,000 guilders including the value of the owners’ two cars. The business grew as the competition—major producers that controlled long-term contracts—began breaking apart in the late 1960s and ’70s. Small traders, including Vitol, started buying and selling oil on the nascent spot market.

“It was tricky,” Detinger says in an interview in London. He’s sitting alongside Taylor—recalling some “very dangerous” moments, such as the first oil crisis in 1973-74, when the price of refined products fluctuated wildly.

Back then, the energy market had yet to develop any futures, options or swaps contracts to hedge price risks, so traders like Vitol were facing a massive exposure every time they bought a cargo: If the market moved against them, they could loss everything.

As business grew, Vitol expanded geographically, opening offices from Switzerland to London to New York. Tension followed, with the founders split on strategy. In 1976, Viëtor, then CEO, left, and Detiger took over. By the time Taylor joined to run the crude oil side of the business, Vitol was handling about 450,000 barrels a day—a decent figure but only half what the industry’s leaders did. The kings of the oil trading game back then were Phibro, which had just bought Salomon Brothers, the investment bank, for $550 million; Marc Rich + Co., founded by the eponymous trader and onetime tax fugitive; and Transworld Oil, controlled by John Deuss, who’d risen to prominence and infamy by doing business with South Africa in the days of apartheid.

The modern Vitol began to take shape in 1990, when Detiger and seven other partners sold the company for $100 million to $200 million (the actual figure wasn’t disclosed) to a group of about 40 employees, including Taylor. The management buyout was financed by what was then ABN, the Dutch bank, and trader Ton Vonk took over as CEO.

Since that time, no single shareholder has controlled more than 5 percent, creating what Taylor and others describe as a “we” culture that’s the cornerstone of Vitol’s success. “If anyone thinks they are bigger or better than the sum of the entity,” says Bake, “he tends to get indirectly smacked down.”

Vonk pushed Vitol into crude trading, expanding beyond refined products, and started signing so-called processing deals with refiners, supplying crude and receiving fuels. Those agreements led to what would be the most profitable deal ever for Vitol—and one that also almost brought the company down.

In the early 1990s, Vitol was processing crude at a seemingly cursed refinery in a town called Come by Chance on the eastern edge of Canada. When a fire tipped the refinery into bankruptcy, Vitol bought it for $300 million in 1995, then booked a $1 billion profit when it sold the plant a decade later. It remains the company’s best-ever return from a single deal.

What’s little known is that Vitol almost went belly-up as it struggled under the cost of upgrading the Come by Chance refinery just as its trading business floundered. In 1997 net profit fell to just $6.6 million, far below the consistent earnings ranging from $60 million to $70 million it achieved in 1992, 1993, and 1994 before it bought Come by Chance. As an investment, the refinery “was too big” relative to the company’s size, says Kho Hui Meng, head of Vitol in Asia.

The experience continues to resonate. In the wake of Come by Chance, Vitol became fanatically conservative and overcapitalized. (Rating companies S&P Global Ratings and Fitch Ratings privately give Vitol an investment-grade BBB rating, according to a presentation reviewed by Bloomberg Markets.) Since then, Vitol has sought out partners, including an Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund, when buying assets. Today it co-owns five refineries with a capacity of 390,000 barrels per day. But Kho says Vitol never forgets its key strength. “Our core business is trading, moving oil from A to B efficiently,” he says.

On a sunny April morning in Rotterdam, Jack de Moel oversees the bread and butter of Vitol’s business. The company owns the massive Euro Tank Terminal here, which De Moel manages, and the barges Noorozee and Citrine are taking on fuel oil from tank 404, which rises taller than a 10-story building. A few meters away, a big tanker, the 144-meter-long (472-foot) Blue Emerald, is also loading fuel ahead of a North Sea crossing. Its ultimate destination is the Thames Estuary in England.

The terminal loaded 3,900 barges and tankers last year—one every two and a half hours. Each of those ships represents a potential profit, albeit a relatively small one. As the round-the-clock work here shows, oil trading is a business of big volumes but razor-thin margins. It also requires a huge investment. Since 2006, Vitol has built 28 towering storage tanks alongside Rotterdam’s deep-water Calandkanaal. They can hold enough fuel to fill up 22 million Volkswagen Golfs.

Vitol’s financial health isn’t linked to oil prices the way Big Oil’s fortunes are. “We are long volatility,” says Paul Greenslade, who was Vitol’s head of trading until he retired in 2014. That’s industry jargon meaning Vitol benefits from price fluctuations, regardless of market prices. In 2009, for instance, the year the company reported its best profit, oil plunged to $30 a barrel from a record $150. Last year, as most of the energy industry struggled amid cascading oil prices, Vitol reported its fourth-highest profit.

For Vitol, oil is just a starting point. It blends different fuels to create the exact grade needed for each region, customer, and even season. To ensure supply, Vitol will provide cash upfront to companies such as Russia’s Rosneft or governments like the one that runs oil-rich Kurdistan in northern Iraq—more than recouping its money when it sells the oil.

“The perception of them is as speculators,” says Craig Pirrong, a finance professor at the University of Houston. But, in reality, he says, Vitol is an intermediary between consumers and producers. It will turn supertankers into floating storage farms, timing sales to beat roller-coastering prices. In 2015 it hired one of the world’s largest tankers—a 380-meter vessel as long as the Empire State Building is tall—to store crude. On any given day, Vitol has about 200 ships at sea. Last year the company logged 6,629 ship voyages.

For the most part, Vitol is a passenger riding the oil market. Sometimes the market severely restricts profit-making; this was the case in 2012, 2013, and the late 1990s. At other times, the market provides opportunities, often unexpectedly. The war in Libya was one such case; the 2011 nuclear crisis in Fukushima was another, leading to a massive shift in energy flows to Japan. “Opportunity is defined externally,” says Russell Hardy, a senior Vitol executive. The job of the company’s traders, he says, is to find ways to profit from those opportunities.

Vitol’s opportunity-driven culture has forged a fiercely loyal staff. It can’t hurt that many have become fabulously wealthy. They keep a notoriously low profile, and little is known about their individual wealth. However, a messy divorce proceeding a decade ago involving one of the company’s most senior traders offers a rare glimpse into Vitol’s riches.

According to documents filed in Texas’ 14th Court of Appeals, Mike Loya, who heads the company in the Americas out of Houston, controlled Vitol shares valued at $140 million at the end of 2007. Since then, Vitol’s book value has almost doubled, with profits and payouts surging, suggesting that top executives are each worth hundreds of millions. Loya says that what lured him to move from his old job at Transworld in the 1990s was a chance to earn a stake in a dynamic business. “If you do well, you become one of the owners,” he says.

In 2014 alone, according to documents reviewed by Bloomberg Markets, Vitol distributed a special dividend-like payment of more than $1.1 billion to its 350 or so employee shareholder-partners. From 2008 to 2014, these shareholders were awarded payouts totaling almost $5.6 billion. Even so, says Chief Financial Officer Jeff Dellapina, “over the past 10 years we’ve reinvested 50 percent of the profits in the business—an appropriate level for an established and growing company.”

Vitol is a private company in more ways than one, and it’s never found the oxygen of publicity to be particularly inviting. “When Vitol makes headlines, they are bad headlines,” says Oliver Classen of the Berne Declaration, a Swiss nongovernmental organization that has researched commodity trading and advocates formal regulation of the industry.

In 1995, for instance, Vitol paid a Serbian warlord $1 million for help resolving a business dispute. Zeljko Raznjatovic, known as “Arkan,” was indicted in 1997 by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia in The Hague for crimes against humanity. He was assassinated in 2000 before his trial could go to court.

Vitol took its most damaging reputational hit in 2007 over paying the regime of Saddam Hussein about $13 million in “surcharges” to secure oil shipments under the United Nation’s scandal-plagued Oil-for-Food Programme. The investigation, led by Paul Volcker, the former U.S. Federal Reserve chairman, exposed a world of illicit payments, secret bank accounts, and diplomats for hire. Rather than paying a fine without admitting wrongdoing, Vitol agreed to plead guilty in the Supreme Court of the State of New York; other companies, including Chevron, resolved similar civil and criminal cases at the time, but only a few pleaded guilty. “We did a settlement to protect our own staff,” Taylor says, suggesting that without the deal, U.S. prosecutors could have charged individual traders. He points out that there were plenty of others paying the same surcharges. “It was chaos,” Taylor says of the UN program.

Vitol’s reputation was rattled again in 2012 after the company purchased Iranian fuel oil, skirting U.S. and European Union sanctions. Vitol, which used its Bahrain subsidiary for the deal, denied wrongdoing. Nonetheless, the episode marked a watershed for the company. Scarred by bad publicity and the negative reaction of some of its banks, Vitol tightened its internal compliance standards. Other changes soon followed. The company, for example, scaled back much of its trading activity in Nigeria as corruption allegations piled up against officials under then-President Goodluck Jonathan.

Even so, Vitol lags in disclosing information that activists such as the Berne Declaration consider imperative. While Glencore and Trafigura have joined a voluntary scheme to improve transparency in the commodity sector, Vitol has resisted. Unlike other privately owned traders, including Cargill, it refuses to disclose its financial results.

Taxes are another rallying point for critics. In 2015, judging from calculations based on the company’s accounts, Vitol paid an effective global tax rate of 14.1 percent, less than half of Goldman’s 30.7 percent. Although Vitol is incorporated in Rotterdam, the partner-owners control it through two Luxembourg-based shell companies, Vitol Holding II and the Tinsel Group, according to information disclosed in the Loya divorce papers. It settles a large chunk of its trades in tax-friendly jurisdictions, including Switzerland and Singapore, longtime hubs for commodity traders. “Our main trading offices were established a long time ago in key trading centers,” says Dellapina.

Although Vitol isn’t the only company that tries to reduce its tax bill, it’s been particularly successful at it. In 2013 it paid no tax at all—thanks to the use of tax credits—in a year when its net income was $837 million.

Even though the CEO and most top executives are based at the company’s sleek, minimalist offices near Buckingham Palace, Vitol pays the bulk of its corporate taxes outside Britain. Criticism of Vitol’s tax practices—from the Scottish National Party and others—has been exacerbated by Taylor’s donations of more than $2 million to U.K. Prime Minister David Cameron’s Conservative Party and to causes supported by him. “Vitol has an open and transparent relationship with the tax authorities in all the jurisdictions in which it operates and pays its corporate taxes in each of these jurisdictions,” Dellapina says.

Having thrived for more than two decades, Vitol may need to prepare for choppier seas. Trading margins keep shrinking as the minute-by-minute movements of the global oil industry are disseminated on the internet. Possession of market information that others don’t have—once Vitol’s edge—is fast disappearing. So what will Vitol do?

As quick-witted as he usually is, Taylor struggles a bit to answer the question over his breakfast at St. Pancras. “You will be surprised,” he finally says. “I don’t know the answer.”

After mulling things over, he says Vitol will benefit from “natural market growth.” He also says he wants to buy more assets to complete the creation of what in the oil industry is known as “a system”—a cache of oilfield stakes, refineries, tanks, and petrol stations spanning the cycle from the ground to the gas tank—just like Big Oil. It would be Vitol’s own brand of vertical integration, he says, featuring minimal investment or exposure to actual oil production. “I will kill—kill!—to have that system,” he says.

Although building such a structure wouldn’t come cheap, Taylor, along with his colleagues, is determined to stay private. Glencore’s 2011 initial public offering, which created several paper billionaires overnight, doesn’t tempt Taylor or his team, he says.

At least that’s the case now. Bob Finch, a former Vitol senior executive and for years the largest shareholder, says Vitol considered the idea of hiring a bank to explore going public about 10 years ago. Unbeknown to those outside Vitol’s inner sanctum, the IPO option reached the executive committee, where it was defeated by what Finch says was a “narrow vote.” Taylor says the idea of hiring a bank was “rejected by most members” of the executive committee.

Over the course of Vitol’s history, a number of companies expressed an interest in buying the oil trader. At one point, Vitol talked about selling a stake to Petronas, the state-controlled Malaysian oil company with which Taylor had developed a close relationship during his time in Singapore. It didn’t happen. Perhaps the most serious conversation happened in the late 1990s when Enron considered buying the oil trader. The partners turned down the offer, thereby staving off a disaster: Enron, which went bankrupt in 2001 amid an accounting scandal and criminal investigations, was offering to pay with its own shares, which later turned out to be worthless.

The biggest challenge for Vitol may be internal as it wrestles with succession. Transitions at other trading houses show they’re anything but easy. Taylor, who recently battled throat cancer that’s in remission, says he isn’t going anywhere soon. But he and at least three other members of the nine-member executive committee are either past or near 60. His lieutenants—including David Fransen, who heads the office in Geneva, Loya in Houston, and Kho, the boss in Singapore—will at some point retire. Vitol has been grooming the next generation—including Hardy, Dellapina, Bake, and Mark Couling, head of crude trading—to take the baton. One of these men, all in their 40s or 50s, is expected to be the next CEO.

Until then, Taylor says he’s adhering to his usual schedule, which means traveling for almost half the year. The commodities business is still ruled by the centuries-old pledge of “my word is my bond.” Face-to-face meetings are imperative.

“You need to have relationships,” he says. Which is the reason Taylor flew into Benghazi—a deal he didn’t want to do “unless I knew who I was dealing with,” he says. “It could have gone very, very badly wrong.”

And with that he’s off to catch the Eurostar—in search of the next deal.

Recommended for you