The biggest oil-industry downturn in a generation has companies collaborating in ways they never thought possible.

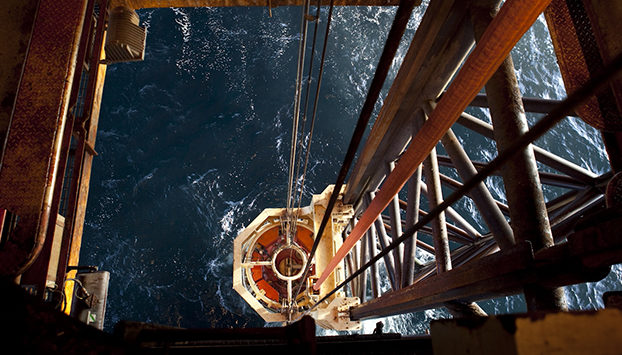

In this global effort, one of the world’s most expensive oil regions intends to lead the way. Last month companies operating in the North Sea started pooling spare parts and tools, and they are even sharing plans on how to drill wells so they can work faster and cheaper, said Paul Goodfellow, Royal Dutch Shell Plc’s vice president for the UK and Ireland.

This is a big change from oil’s boom, when costs weren’t such an issue as long as $100-a-barrel crude kept flowing. As companies focus on adapting to prices closer to $50 by making their spending less wasteful, they also aim to boost profitability for years to come by keeping costs low as markets recover.

“We didn’t particularly focus with the same urgency on costs when oil and gas prices were high,” said Colette Cohen, senior vice president of U.K. and the Netherlands for Centrica Plc, a natural gas supplier. “Now it’s about coming in every day and thinking how can I do that better, or how can I reduce costs,” but it’s “very difficult” to keep this going when prices recover, she said.

Companies responded to the price slump by reducing spending, potentially cutting as much as $1 trillion by 2020. The industry has reduced costs by 10 percent to 15 percent overall, but in the U.K. about three-quarters of these savings are linked to things like rig-rental rates, which typically go back up when oil prices rise, said Malcolm Dickson, principal analyst at consulting firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

The Shell-led initiative in the North Sea aims to avoid that.

“You can sit there in a world of $100 and think all is good and not maybe realize how fragile the system is,” Goodfellow said in an interview in Aberdeen, Scotland, the center of the U.K. oil industry. “You’ve had the shock and that’s illuminated the problem.”

Shell and partners including EnQuest Plc, Marathon Oil Corp., Apache Corp., Centrica and Repsol SA’s Talisman started talking last year about setting up a pool of spare parts, ranging from nuts and screws to valves and compressors, Goodfellow said. They formed a group to manage the inventory, contributed their excess equipment, cataloged it and found a warehouse in Aberdeen to store more than 200,000 parts.

The system, which is managed by a company called Ampelius Trading, came online a few weeks ago. So now, for example, if Shell needs a valve for a North Sea facility, it can log on to the system, go through the catalog, place an order and have the part delivered the next day instead of waiting “six weeks, six months,” Goodfellow said.

Shell is also leading a group called the Wells Forum, which asked members to share their drilling plans so others could give their opinion and experience on how to reduce costs, Goodfellow said. Shell, BP Plc and France’s Engie SA were the first to put up their well plans and seven others followed, helping cut costs by at least 10 percent, he said.

Overall, operating costs in the area have fallen as much as 40 percent in the past two years, Goodfellow said.

While this cooperation is “very desirable,” it’s not enough to fully compensate for current low oil prices, said Nick Butler, visiting professor at the Policy Institute at Kings College in London and former vice president of strategy at BP. Investment cuts in the area will start to affect production from 2018, he said.

Still, lots of incremental savings can add up to significant cost reductions for individual projects. Statoil ASA and its partners have cut the estimate for capital spending on the giant Johan Sverdrup field in the Norwegian North Sea to 160 billion kroner to 190 billion kroner ($19.3 billion to $22.9 billion) from 170 billion kroner to 220 billion kroner previously.

Fewer wells are being drilled, production vessels are being changed and the standardization of equipment like underwater valves makes cost reductions more sustainable, said Wood Mackenzie’s Dickson.

BP CEO Bob Dudley says the industry can do a better-than-expected job of keeping costs low.

The company’s Mad Dog Phase 2 project in the U.S. Gulf of Mexico is now expected to costs less than $9 billion compared with an estimate of $10 billion last year and $20 billion four years ago, Dudley said. Rig-rental rates are likely to stay down because of an oversupply, while low steel prices are reducing the cost of other equipment, he said.

“That’s too pessimistic” to say that most savings will be lost when the industry rebounds from the downturn, he said in an interview in St. Petersburg, Russia, on June 17. “For our organization, we believe we can capture 75 percent of the cost reduction and keep them there.”

Recommended for you