Norway’s oil industry says it has some major investments in store if the government can just come through with some tax incentives.

It’s still hoping for tax breaks to encourage recovery of oil from older fields. Those failed to materialize over the past four years even as the industry went through its worst investment collapse in a generation.

As Norway heads into an election next month, the oil industry still has “some expectation” that whoever wins will consider those incentives, said Karl Eirik Schjott-Pedersen, a veteran politician who leads the Norwegian Oil and Gas Association.

His main argument: tax breaks could help trigger investments of about 150 billion kroner ($19 billion) which might otherwise not happen, according to a study the group commissioned in 2015.

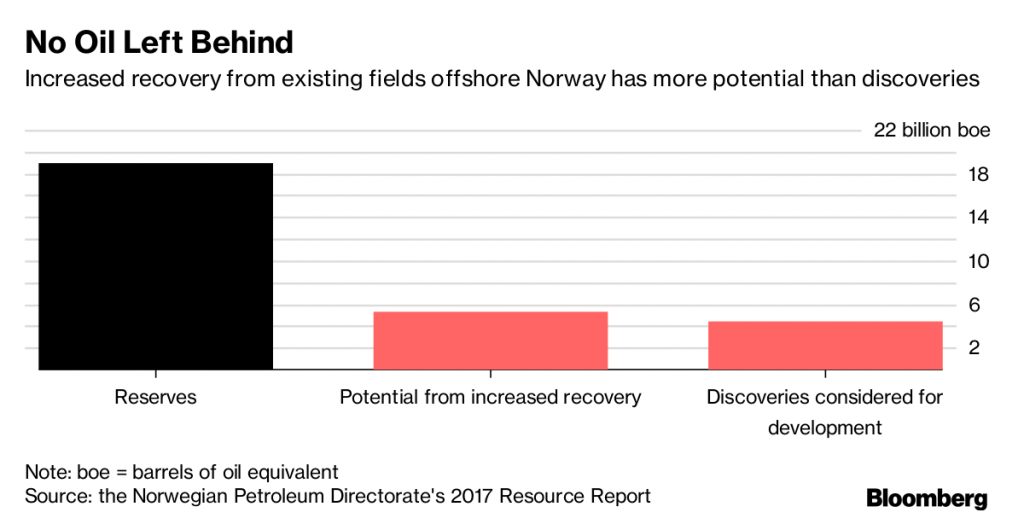

“Raising the recovery rate in fields would create enormous value,” Schjott-Pedersen, who has served as finance minister for Labor among other cabinet posts, said in a phone interview on Thursday. “It’s also critical that it’s done now, given that it depends on either the fields or the infrastructure still being in operation.”

These projects would give a welcome boost to the supplier industry, which has seen tens of thousands of jobs disappear after oil prices plunged in 2014. They could also bring in about 135 billion kroner in taxes, at a time when the government’s petroleum revenue has dropped to the lowest this century, forcing it to raid its $970 billion sovereign wealth fund for the first time.

None of this persuaded the Conservative-led government to offer tax breaks, which said after winning elections in 2013 that it would consider such incentives. Instead, the administration has insisted oil companies have an obligation to produce all profitable barrels, putting pressure on state-controlled Statoil ASA and others to commit to investments.

“It’s unwise that they haven’t seized the opportunity,” Schjott-Pedersen said. “But we still have a hope that the parties, regardless of who governs, will see the wisdom in creating those jobs and securing that income for society.”

The Conservative Party repeated in its election program that it will consider tax measures to boost recovery, and the Progress Party, its government partner, went further saying it wants to provide stimulus for higher production at mature fields. Labor doesn’t address the issue in its program, and the party’s spokesman for energy matters didn’t reply to a call seeking comment.

Schjott-Pedersen was one of the most important members of Prime Minister Jens Stoltenberg’s Labor-led government, which right before being voted out in 2013 actually increased taxes for oil companies, by reducing the so-called uplift, an extra deduction for investments.

“Any reduction in the uplift weakens the incentive for increased recovery from mature fields,” Schjott-Pedersen now says, stopping short of calling the 2013 move a mistake.

Still, tax breaks for oil companies may not be a vote winner in Norway these days, amid a growing debate over the role of western Europe’s biggest oil and gas producing nation in fighting climate change. Polls suggest advances for the Green Party, which got its first ever lawmaker in 2013. Many of the smaller parties in parliament are also arguing for scaling back the industry while a continued ban on drilling off the shores of the environmentally sensitive Lofoten islands seems likely, no matter who’s in power.

One argument goes that investing more in oil production is tantamount to throwing money into the sea since the renewable energy revolution will likely dry up demand for fossil fuels. A recent poll showed the Norwegian people are pretty evenly split on whether Norway should leave oil in the ground.

But the industry argues it still enjoys “very broad support” among the population, at least in terms of what it means for jobs and welfare, Schjott-Pedersen said. The biggest parties still agree to maintain stable framework conditions and continue awarding new exploration acreage. The Conservative-led government has overseen a record push into the Arctic Barents Sea, with the support of Labor.

“The big lines in Norway’s oil and gas policy remain firm,” Schjott-Pedersen said. “There’s broad consensus about them.”

Recommended for you