The US oil price experienced a considerable comeback in the second quarter, with the benchmark WTI nearly doubling from $20 at the end of March to the current ~$40. This recovery was driven by the substantial oil supply cuts from OPEC countries and their alliances (OPEC+) and faltering domestic US production amid low oil prices. This improved oil demand also contributed to the price recovery.

Of these positive factors driving the recovery of the oil market, the supply side of the story has been central to the narrative. The magnitude of production cuts from OPEC+ was unprecedented: the 9.7 mmbd production cut, nearly 10% of total global production, dwarfs the prior production cut of 1.5 mmbd made by OPEC+ in 2016. With an even deeper cut, the rebounding oil price is unsurprising.

Now with the price being pushed higher by the initial deep production cut, the durability and magnitude of oil price recovery is in question. Recent oil price movement indicates that the market is seeking new catalysts. However, recent market developments may signal that price recovery will likely be suspended or even face a setback.

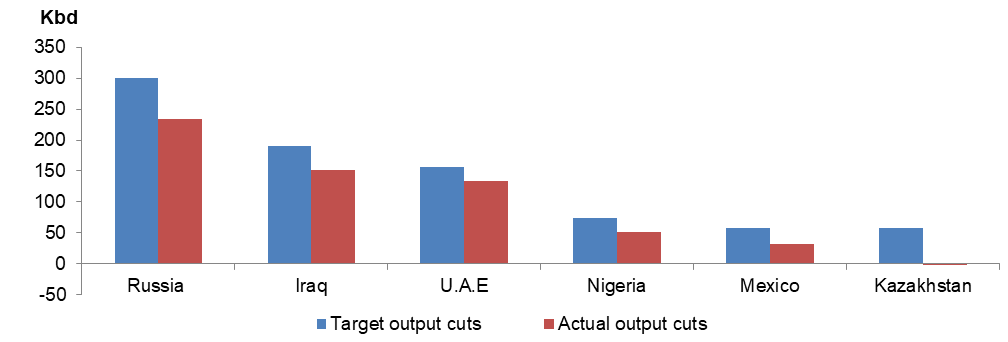

First, the pace of production decline has already moderated. Regarding the cut from OPEC and Russia, Reuters reported that OPEC cut compliance in June reached above 100%, recording the lowest monthly output number in 20 years, due to additional voluntary cuts mostly from Saudi Arabia. A cut of this magnitude is likely to peak, and future cut compliance is seeing signs of relaxation. The problem remains of production cut compliance in the remaining OPEC+ countries. For the largest part, Russia and Iraq have been consistently unwilling to adhere to the quota; in the last OPEC cut in 2017, they did not meet their production cut targets for long. True to form, they are currently the laggard once more, and may not catch up with their quota target anytime soon. Second, according to news reporting, OPEC+ is discussing a potential easing of cuts from August and Saudi is waging a price war against non-compliant countries. Though these developments are still in their early stages, the motivation to ease the cut and benefit from the rising price is understandable. Thus, the most significant cut may have already occurred, with further production reduction potentially being limited on the OPEC+ side.

Major OPEC+ countries not meeting cut targets (May 2020)

Source: OPEC, IEA

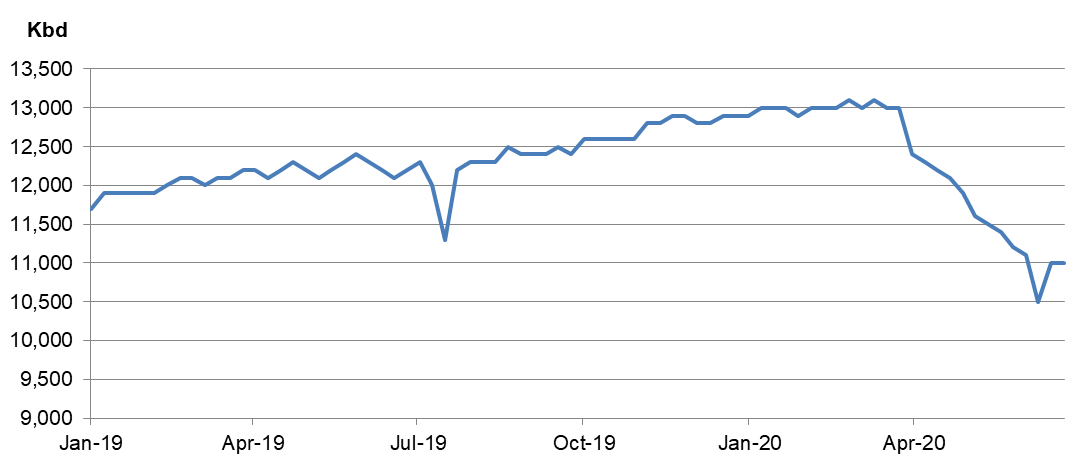

Besides the issue of OPEC+ cut compliance, the pace of US domestic production decline also appears to be moderating. Excluding the effect of production coming offline due to hurricanes, the recent two entries of EIA’s weekly US production data points indicate a deceleration in the pace of production decline. Now with a higher oil price than in the first quarter, US producers are more inclined to produce more to improve their financial position.

US domestic crude oil production

Source: EIA

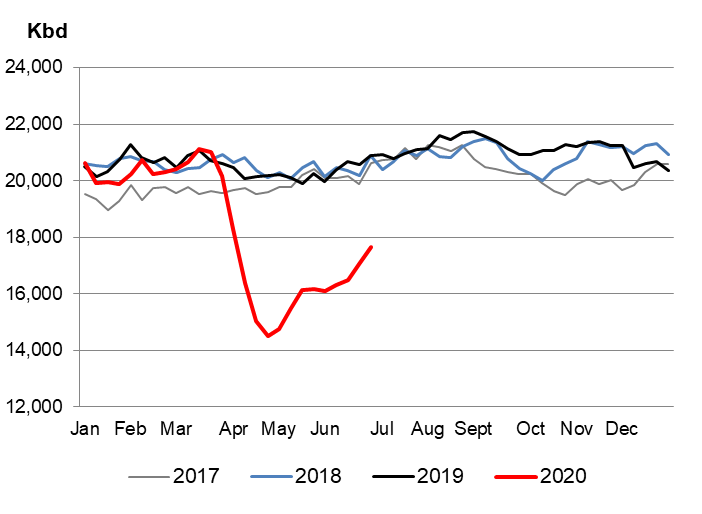

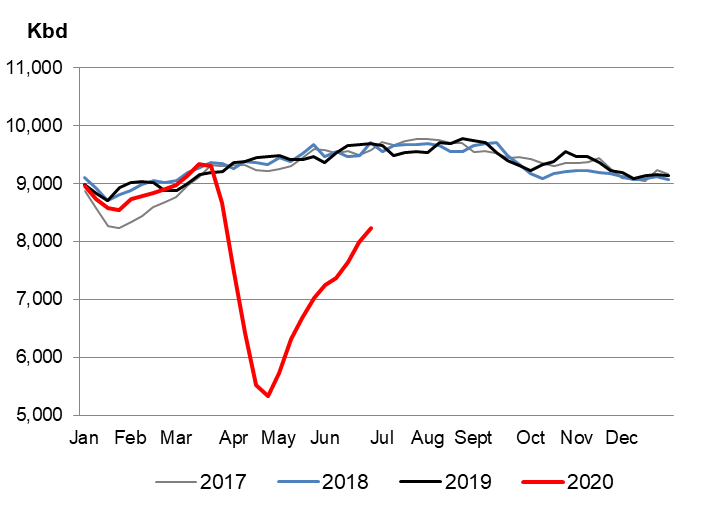

Second, demand recovery is strong so far but may not reach pre-virus levels for long. It may be tempting for people to assume that as their lives get back to normal with more states easing from COVID-19 lockdowns, the demand will subsequently normalize. Due to fears of COVID-19, the possibility that people may prefer to drive their own cars rather than use public transport and flights for travels may further boost oil demand.

US total petroleum products demand US gasoline demand

Source: EIA, all data are in rolling four-week average basis

However, these arguments overlook certain points. First, we have already seen a spike in COVID-19 cases, and some states are already rolling back their plans for re-opening. If the pandemic lingers, neither the economy nor oil demand are likely to return to normal at any considerable speed. People’s behaviors have also changed dramatically, thanks to online shopping, food delivery, and a rise in employees working from home; the need to drive on a daily commute or for the completion of errands has therefore declined. Third, demand from jet fuels may never reach the prior level. The first two months of re-opening saw the return of some necessary activities and a resultant quick recovery of oil demand, but these are low-hanging fruits. Going forward, the pace of demand recovery may be slower.

A slower production fall and demand recovery will lead to slower inventory overhang clearance. The US oil inventory is still extremely high despite the recent decline. Arguably, the oil market recovery is still in its early phases; however, if history offers any guidance, investors can be very impatient.

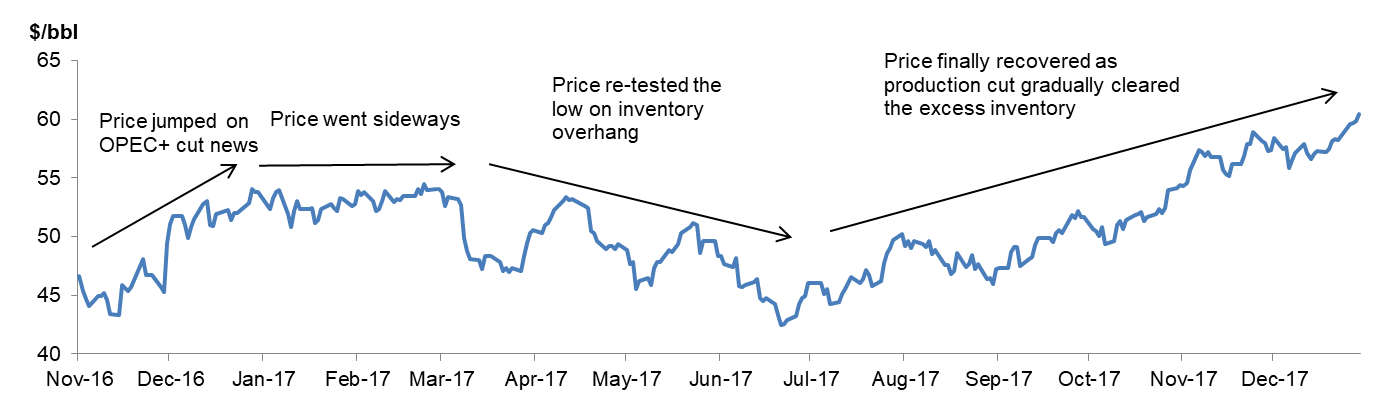

In the prior OPEC+ cut at the end of 2016, the oil price first rebounded with the hope of a production cut repairing the oil market, but lowered after four months; the oil inventory remained stubbornly high, and the production cut didn’t seem to absorb the oversupply.

Path of oil price recovery in 2016 and 2017

Source: EIA

Price recovery is separated into two phases: first, the quick reaction to good news and any marginal improvement; and second, the validation of the effectiveness of oil market intervention. The first phase is often swift but short. The uncertainty that characterizes the second phase – alongside the length of time necessary to clear the inventory overhang – will make investors jittery and doubtful, making the path of price recovery bumpy.

In the current situation, a similar story of oil price recovery is to be expected. Though investors may have gained confidence in OPEC+ market intervention from its previous success, this time the situation is more complicated. The most recent oil market downturn was mainly due to oversupply while demand held well, thus a production cut could work. This time, an oversupply of oil coupled with diminishing demand due to COVID-19, indicates that a production cut only solves one side of the equation. As COVID-19 is still a widespread issue with the risk of a second wave emerging, the uncertainty of demand recovery is also increasing.

The saying “buy the rumour, sell the fact” is appropriate in this context. Although the market may quickly rally in the hopes of an effective production cut, in reality it will take longer than expected for the cut to produce a tangible effect. Markets can thus go sideways or be set back on uncertainty.

Recommended for you