The energy transition is a “political risk nightmare” for hydrocarbon-export reliant states, a new report from Verisk Maplecroft has said.

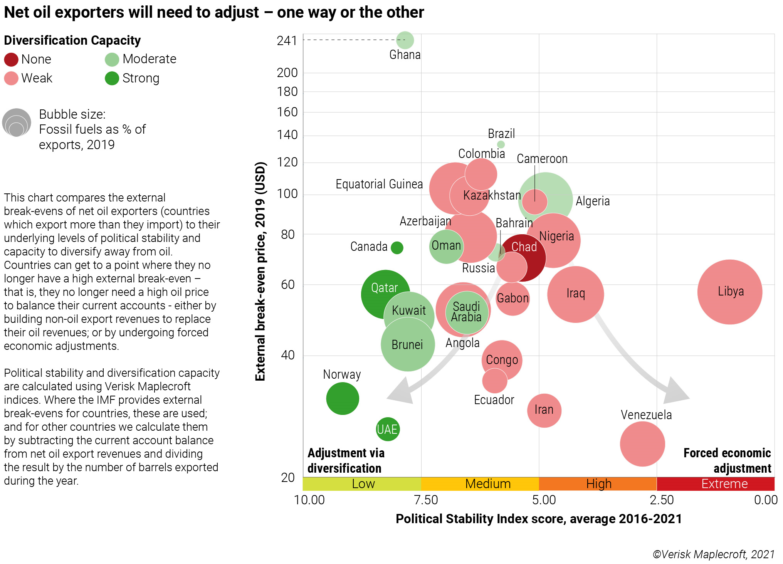

The risk consultancy picked out Algeria, Iraq and Nigeria as the first casualties of the change. There will be a “slow motion wave of political instability” over the next three to 20 years as the energy transition takes hold, the report said.

Time is running out, the report said, for countries that have failed to broaden their economies beyond exporting fossil fuels.

Those that fail to diversify their economics face “political instability and market turmoil”, Verisk Maplecroft’s analyst Franca Wolf told Energy Voice.

“These countries’ weak diversification capacity partially stems from weak political institutions, which already make them more vulnerable to political instability.

“As living standards fall and existing social contracts come under pressure, there is a high risk that inadequate channels for expressing social discontent will result in political turmoil – which may or may not be violent, but will certainly be disorderly,” she said.

Transition trouble

Most of the countries at risk are in West Africa. These include Chad, Angola, Gabon, Congo Brazzaville, Cameroon and Equatorial Guinea. This six, along with Azerbaijan, are next “in line for trouble” as the energy transition continues, the report said.

Verisk Maplecroft’s report also warned that these countries would be at the front of the queue for majors looking to de-risk their portfolios.

Verisk Maplecroft’s report also warned that these countries would be at the front of the queue for majors looking to de-risk their portfolios.

Venezuela and Libya have gone through various degrees of state failure and economic collapse. These two show how bad things could get, the report said.

Three factors determine when, if and how badly the storm will disrupt these countries. These are breakeven costs, capacity to diversify and political resilience.

Wolf, one of the lead authors, said reducing external breakevens would “require forced economic adjustment”, either through devaluation or drawing down foreign exchange reserves. This “would effectively rebalance economies’ import and export bills at the expense of living standards”.

This would be “short sighted” and increase the risk of political instability, she continued.

Status no

A lack of diversification stems from a range of economic, political, legal and social factors, Wolf continued, giving Nigeria as an example.

“Added to deep-seated weaknesses in political institutions, including corruption, it’s very unlikely that these countries can move away from the status quo to undergo the required reforms.”

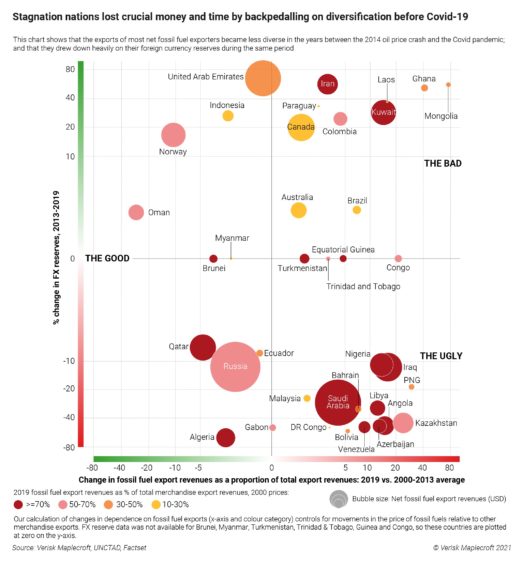

Most oil and gas exporters have “become less diverse” since the 2014-15 and 2020 oil price crashes, the analyst said.

“Even those countries we consider more capable of diversifying have lacked the political will and/or economic ability to move away from oil,” Wolf said.

Saudi Arabia launched its Vision 2030 in a bid to move beyond oil exports. However, the country has actually become more reliant on exports since 2014.

The Middle Eastern producers hold up better than West Africa, according to Verisk Maplecroft’s metrics. The report said these countries may even thrive at points. A lack of new investment in projects may lead to times where demand outstrips supply.

However, authoritarian control cannot guarantee long-term political stability, the report said.

The exception to the rule on oil producers is Norway. The Nordic state launched initiatives following the 2014-15 crash. It has “had some reasonable success in reducing its oil reliance”, Wolf said.

Recommended for you