Amid all the talk of a looming oil supercycle, Energy Voice considers the prospect of a potential supply crunch, rising demand, and triple digit oil prices in the coming years.

Amid all the talk of commodities supercycles, international crude benchmarks hit 14-month highs in March. At the same time, rumblings that oil could top $100 per barrel as early as next year could be heard in the market.

Azerbaijan’s Socar Trading predicted Brent crude could hit triple digits in the next 18 to 24 months. Bank of America expects potential spikes above $100 over the next few years on improving fundamentals and global stimulus measures, which look set to stoke inflation across the commodities space.

Start of a new commodities and oil supercycle?

Bankers at Goldman Sachs have declared the start of a new commodities supercycle. Meanwhile, speculators have also been getting in on the action, boosting bets in the options market that oil will hit $100 by December 2022.

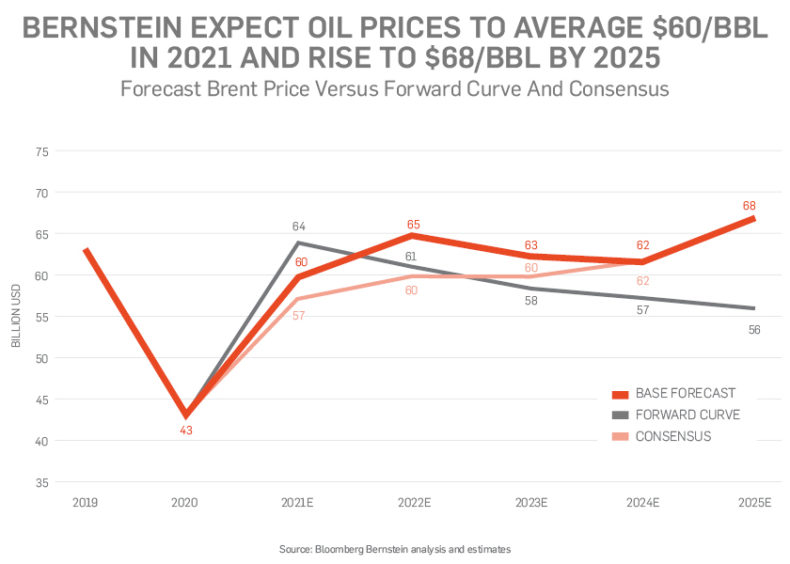

However, projections for $100 a barrel of oil are far from the current consensus. The median analyst forecast compiled by Bloomberg has Brent staying under $65 a barrel through 2025. Still, in March, Brent broke above $70 a barrel for the first time in more than a year, helped by the successful OPEC+ production cuts.

Nevertheless, the International Energy Agency (IEA), in mid-March, reported that oil markets are not on the verge of a new price supercycle as supplies remain plentiful. The IEA added that concerns of a supply shortfall are misguided. Others disagree.

Natural resource investment company Goehring & Rozencwajg believes we are at the cusp of a global energy crisis that will see oil prices rocket towards $100. “Like most crises, the fundamental causes for this crisis have been brewing for several years but have lacked a catalyst to bring them to the attention of the public.

The looming energy crisis is rooted in the underlying depletion of the U.S. shales along with the chronic disappointments in non-OPEC supply in the rest of the world. The catalyst is the coronavirus,” the company said in a report.

“Global energy markets in general, and oil markets in particular, are slipping into a structural deficit,” reckons Goehring & Rozencwajg.

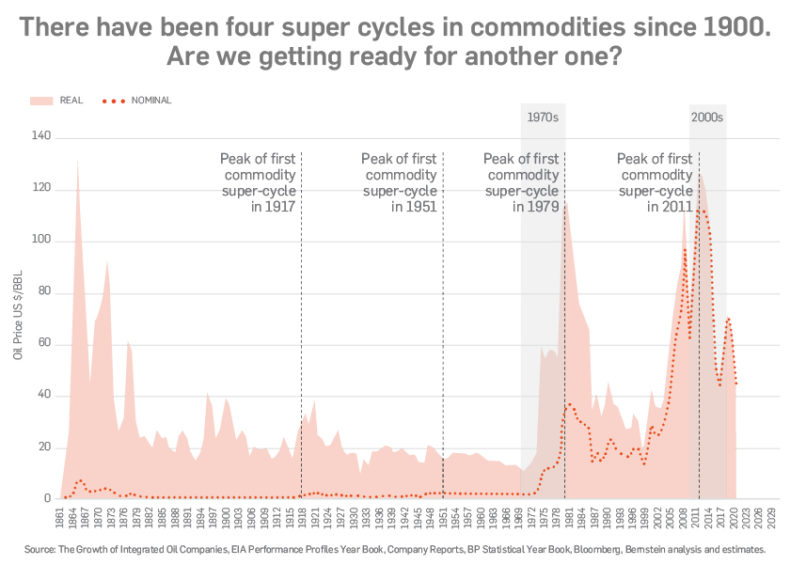

Significantly, structural shifts in supply rather than demand are a more important factor in the creation of super cycles.

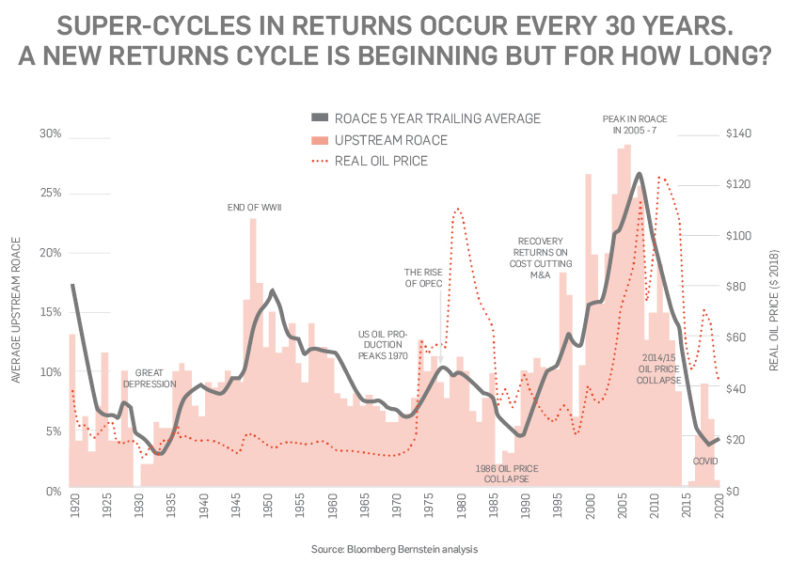

A key argument against another super cycle for oil is that we are close to peak demand. But there is very little evidence from history to show that demand drives super cycles, reported investment house Bernstein. A super-cycle is generally defined as an increase in oil price of several multiples over and above the long-term trend.

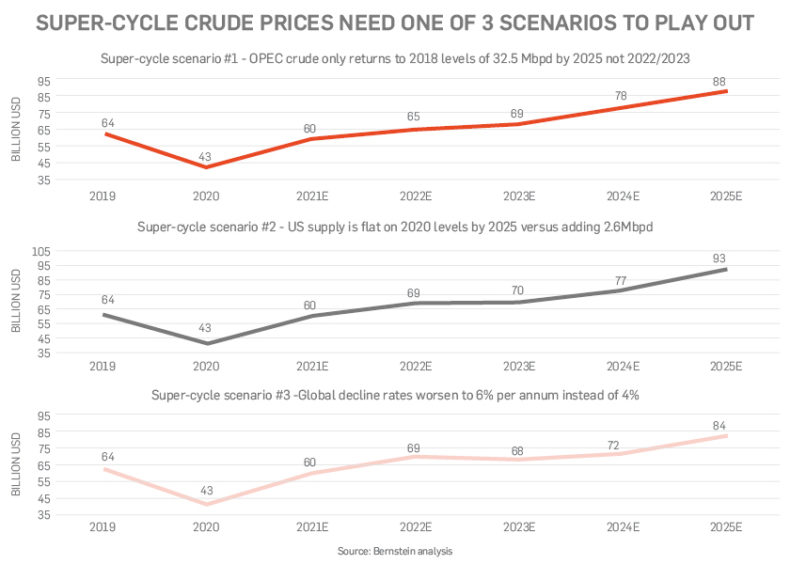

Analysis from Bernstein suggests one of three scenarios are needed to believe in a super cycle for crude: first, OPEC returns its spare production capacity to the market by 2025 not 2022-23 as expected; second, U.S. shale output is flat to 2025 rather than adding 3 million barrels per day (Mb/d); three, global production declines worsen to 6% year-on-year versus Bernstein’s estimated 4%.

Bernstein’s base model signals oil prices closer to $70 a barrel by 2025, slightly ahead of consensus estimates. But supercycle crude prices could range between $84 and $93 a barrel by 2025 should one of the three scenarios play out.

Indeed, “triple digit oil prices, while unlikely, could result from prolonged under-investment,” Joseph Gatdula, head of oil and gas at Fitch Solutions, told Energy Voice.

Is there under-investment in oil production and storage?

Under investment is already happening.

The coronavirus pandemic triggered significant interruptions in the production of oil and storage of oil, which at one point took crude prices into negative territory in April last year. The turmoil sparked drastic cutbacks in capital spending.

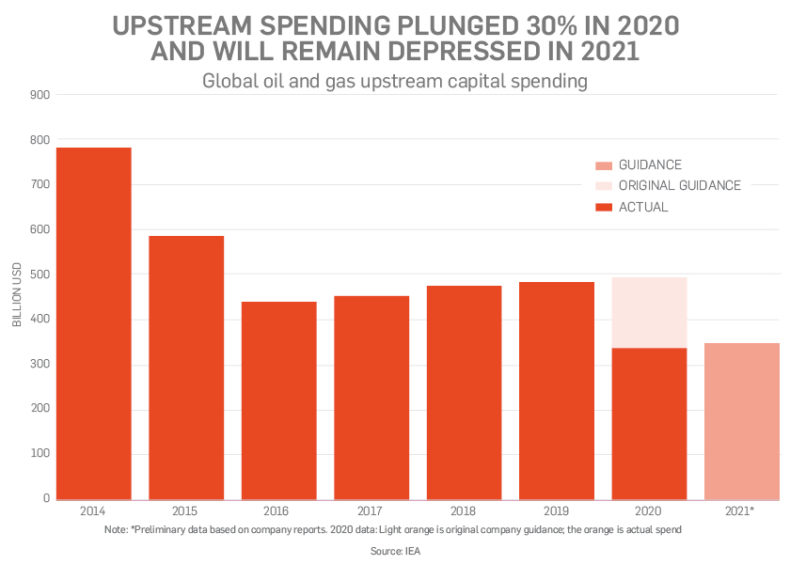

The IEA estimated that upstream investment dropped 30% across the globe in 2020 versus 2019. By comparison, during the severe oil market downturn in 2015, which decimated many producers in the U.S. and Canada, investments fell only 12%. Even before the pandemic, it is arguable that not enough investment was being made in the global upstream sector.

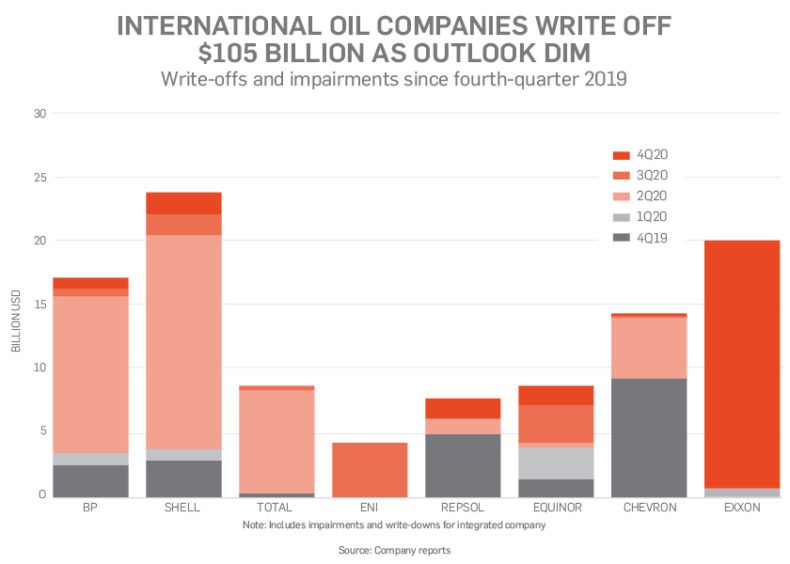

Crucially, the oil sector is now hated more than ever. Even the European supermajors themselves, such as Shell and BP, appear to be going cold on the sector, as the world races towards a cleaner energy system less reliant on dirty fossil fuels, amid rising climate concerns.

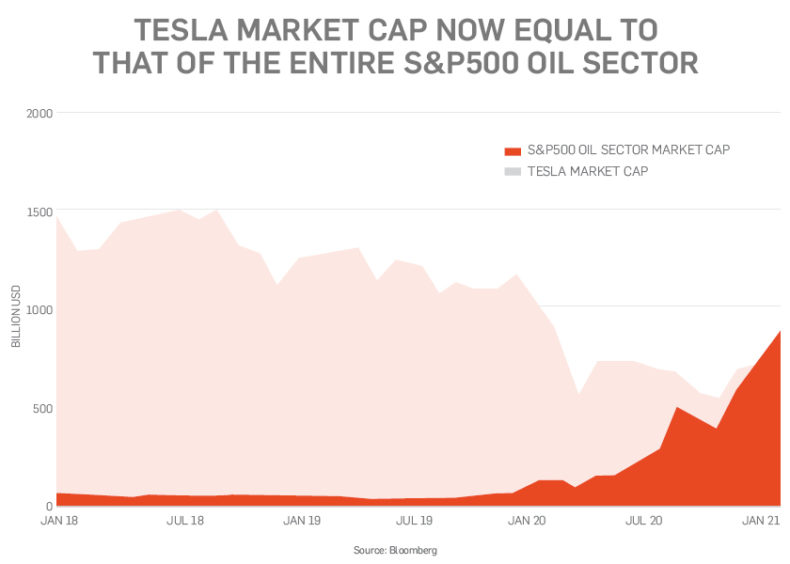

As Dylan Grice, co-founder of Calderwood Capital, an investment company, highlighted in early February, “one image perfectly encapsulates financial markets’ view of the energy sector: The market cap of Tesla today is roughly the same size as that of the entire S&P 500 oil sector, which includes the majors, the independents, the drillers, the service companies and the refiners.

The equity market’s view is clear: oil has no future; the energy transition is here.”

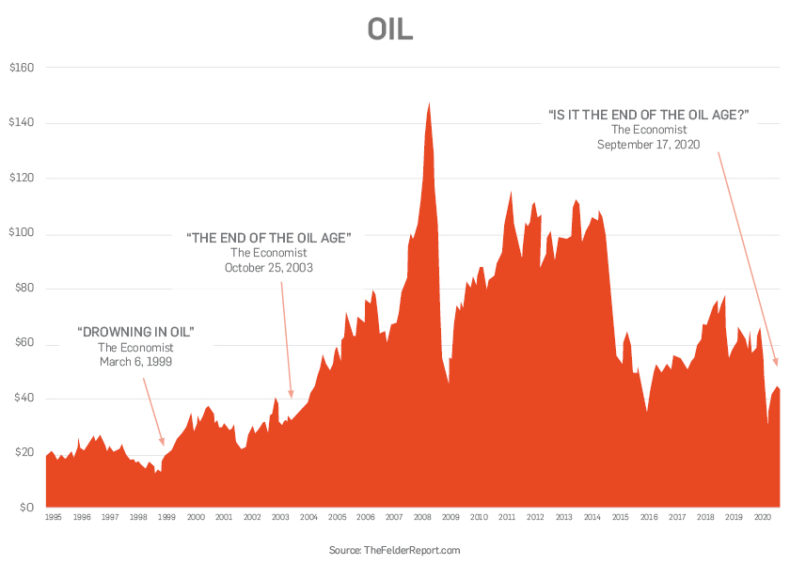

Moreover, as investment analyst Jesse Felder pointed out, aside from energy representing the most hated sector in the stock market, The Economist last September proclaimed the death of oil (once again: see 1999 and 2003). These are screaming bullish signals, reckons Felder.

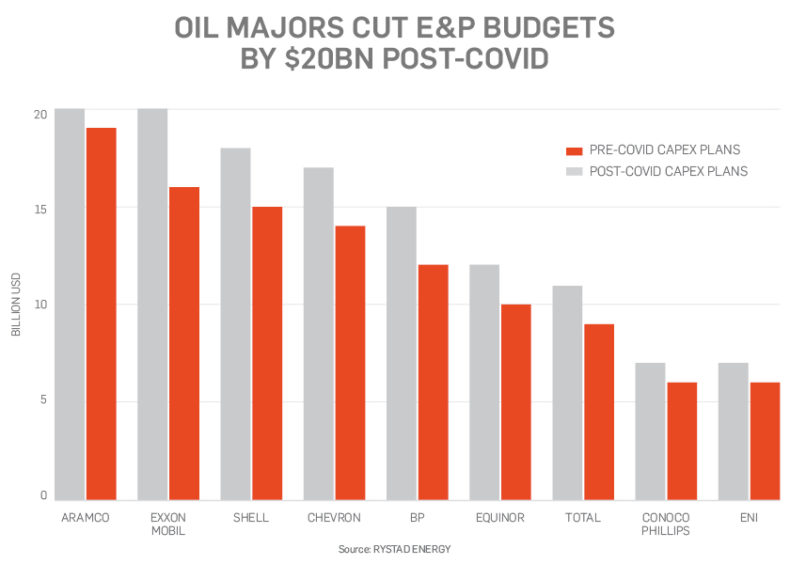

Indeed, most of the majors have cut their capital spending plans.

“Oil has been starved of capital, the whole mantra of the industry is that they are not going to grow anymore, they preserve cash and return it to shareholders.

Even the American shale producers, who easily have the worst track record when it comes to capital allocation, have got this new religion. This is a bull market in the making. It’s just obvious,” said Grice.

Is oil production severely challenged going forward?

In the wake of the coronavirus, the market focus has shifted to how quickly supply can be brought back to meet recovering demand.

“While most investors believe the lost production will be easily brought back online, our models tell us something vastly different. While OPEC+ production will likely rebound, non-OPEC+ supply will be extremely challenged. Instead of recovering, our models tell us that non-OPEC+ production is about to decline dramatically from today’s already low levels,” said Goehring & Rozencwajg.

So far, the slowdown in non-OPEC+ production has come entirely from proactively shutting in existing production. These wells were mostly old and only marginally economic before prices collapsed in 2020, reported Goehring & Rozencwajg.

“Going forward, production will be impacted by a different and longer-lasting force. Low prices led producers to curtail nearly all new drilling activity.

As of March 13,2020, there were 680 rigs drilling for oil in the U.S. In less than four months, the U.S. oil directed rig count fell by 75% to 180 – the lowest level on record,” said the firm.

Shale wells enjoy strong initial production rates but suffer from sharp subsequent declines. Basin production falls quickly unless new wells are constantly drilled and completed to offset the base declines.

Considering U.S. shale production was already falling sequentially back in November of 2019 when the rig count was above 700, the current oil rig count, at 366 as of early March 2021, all but guarantees production will collapse going forward, predicts Goehring & Rozencwajg.

High grading looming?

Significantly, the research firm notes that in previous drilling cycles, sharp slowdowns in activity produced large offsetting increases in drilling productivity.

This phenomenon is known has high grading – when operators stop drilling their least productive prospects first and focus almost exclusively on the areas with the highest average well productivity. Due to this high-grading phenomenon, oil production often falls far less than activity during periods of drilling retrenchment.

The U.S. oil industry has adopted this strategy over the last five years as the shales were dramatically high-graded.

As oil prices collapsed from $100 to a low of $27 in 2016, producers dramatically slowed their activity. Yet, the average well went from having a peak production rate of 400 barrels per day in 2014 to 625 barrels per day in 2018. The surge in high-grading and its huge impact on drilling productivity largely offset the entire slowdown in drilling activity that happened between 2014 and 2018, said Goehring & Rozencwajg.

Last year, in response to oil prices that fell to negative levels in April 2020, rig counts collapsed. Given the magnitude and pace of the drop, productivity should have surged as drillers curtailed their least productive prospects and focused only on their best. Instead, initial production rates deteriorated in each of the major shale basins, added the firm.

This drop in productivity is in sharp contrast to what happened between 2014 and 2017. Indeed, Goehring & Rozencwajg had long argued that future productivity gains would be difficult, if not impossible as shale producers had already high-graded their acreage as much as possible. The firm believes productivity will plateau and then start rolling over.

This may have already started to happen last year

“There is little sign the shales will be able to stop this (production) decline this time around. The industry has underinvested for over a decade and the only thing keeping production robust has been the shales.

Those are now largely developed with productivity stagnating or falling in all major basins. It will be hard if not impossible to keep this market balanced without much higher prices,” Adam Rozencwajg, managing partner at the U.S.-based firm told Energy Voice.

“As investors realise that, the price will keep rallying. I would not be surprised if we approached or even exceeded $100 per barrel this cycle,” added Rozencwajg.

Even some of the shale developers themselves are pessimistic. Scott Sheffield, chief executive and co-founder of U.S.-based Pioneer Natural Resources, the largest owner of Spraberry acreage in the Permian, told attendees at a Goldman Sachs investor call earlier this year that he does not foresee much increase in Permian or wider U.S. shale output over the next several years, and that the Bakken and Eagle Ford shale regions might never see expansion again.

Low prices have also sparked a sharp drilling slowdown in the rest of the world. Between February and June of 2020, the non-U.S. rig count dropped by 40% to 800 – also the lowest on record.

Over the last decade, the non-OPEC+ world outside of the U.S. shales, has seen production fall slowly and steadily, as a dearth of new large projects has not been enough to offset legacy field depletion. By laying down half their rigs, this group ensured that future production would be materially hit, predicts Goehring & Rozencwajg.

Bernstein is not optimistic on non-OPEC ex-U.S. supply growth either. “We don’t believe this tranche of output can materially grow again and won’t exceed the output peak of 2019 (43.3 Mb/d).”

“(Most) analysts continue to focus their attention on what has already happened (the shutting-in of existing production) instead of looking at what is yet to come. The unprecedented drilling slowdown is only now starting to impact production. Going forward, supply will plummet leaving the market in an extreme deficit starting now,” argues Goehring & Rozencwajg.

Energy Aspects, a macro research consultancy, also sees a medium-term supply squeeze happening, as the post-pandemic recovery in oil demand significantly outpaces supply, hamstrung by years of insufficient capital spending, the company’s head of long-term forecasting, Matt Parry, told Energy Voice.

Parry sees Brent crude prices rising to mid-$80 levels around 2023-24. “Crucially, after that we do not then see a sharp decline, our models show prices remaining supported until the early 2030s, as the supply side keeps fundamentals tight,” added Parry.

The IEA’s outlook

Although the IEA said that concerns of a supply shortfall are misguided, the Paris-based agency reported that sharp upstream spending cuts and project delays are already constraining supply growth across the globe.

However, “the historic collapse in demand in 2020 resulted in a record 9 Mb/d spare production capacity cushion that would be enough to keep global markets comfortable at least for the next several years,” the IEA said in its latest mid-term oil market report released mid-March.

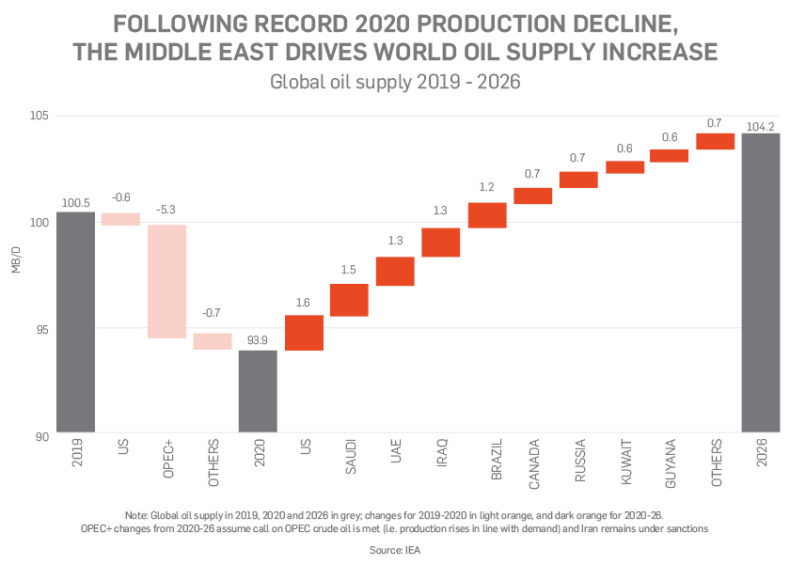

Following the coronavirus-induced demand shock and a shift in momentum towards investment in cleaner energy, the IEA estimates world oil production capacity is set to rise more slowly, expanding 5 Mb/d by 2026.

Crucially, the IEA said that in the absence of stronger policy action encouraging a lower-carbon future, global oil production would need to rise 10.2 Mb/d by 2026 to meet the expected rebound in demand. That’s double the IEA’s currently projected oil production expansion.

Producers from the Middle East are expected to provide half of the increase, largely from existing shut-in capacity.

If Iran remains under sanctions, keeping the world oil market in balance may require Saudi Arabia, Iraq, the UAE and Kuwait – with their surplus capacity – to pump at or near record highs, reported the IEA. Although the IEA does not say it, this starts to sound like a potentially tight supply scenario.

It also marks a dramatic shift from recent years when the U.S. dominated world supply growth. The IEA expects U.S. production to resume its expansion as activity levels climb in tandem with rising prices. Yet any increase will not match the lofty levels of the recent past.

Indeed, the IEA reckons the global market looks adequately supplied through much of the medium term. But in the absence of fresh upstream investments, the spare capacity cushion will slowly erode, warned the agency. By 2026, global effective spare production capacity (excluding Iran) could fall to 2.4 Mb/d, its lowest level since 2016.

Analysts at Enverus Intelligence also see the market amply supplied with non-OPEC short-cycle producers responding to stronger crude prices by boosting rigs and output. This means that OPEC risks having to manage a fresh oversupply picture in 2022 and beyond, reckons Enverus.

“If we see triple digit oil prices, it is more likely to be driven by OPEC’s slow response in returning barrels to the market,” Bill Farren-Price, a director, at Enverus, told Energy Voice.

A Oil and commodity bull run?

Brent oil’s recovery to over $70 this year, from under $20 a barrel last April, has been driven by strengthening demand, OPEC+ production restraint and expectations that the global vaccine push, along with fiscal and monetary stimulus, will bring about a solid economic recovery.

As a result, the seeds of a new price cycle are being sown, said Enverus.

Commodity prices, such as iron ore and copper, along with tanker shipping rates, have surged in the past six to nine months. “Lurking in the background for all U.S. dollar-denominated commodities is the subtle tailwind of a depreciating greenback, driven by rock-bottom U.S. interest rates,” said Enverus.

However, “while the price recovery in many commodities may suggest we’re in the midst of a bull run, prices can be fickle.

A sustainable global economic recovery will be dictated by the virus, its mutations and the pace of vaccinations. While commodity prices are looking bullish right now, we need to be wary of false starts,” cautioned the research company.

Oil demand and recovery path uneven – but driven by Asia production

Oil demand and international crude prices remain very uncertain in the short-term. But global oil demand, still reeling from the effects of the pandemic, is unlikely to catch up with its pre-COVID trajectory, said the IEA.

In 2020, the start of the IEA mid-term oil forecast period, oil demand was nearly 9 Mb/d below the level seen in 2019, and it is not expected to return to that level before 2023.

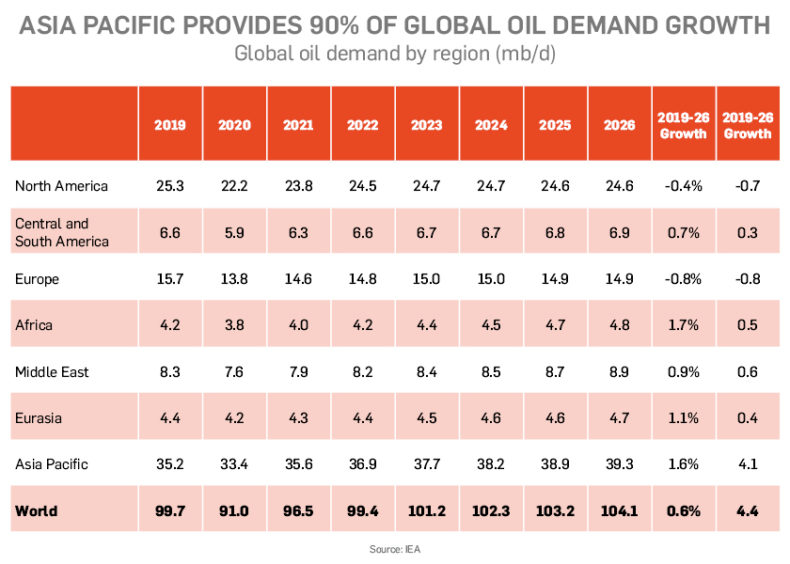

The IEA expects oil demand to continue expanding – rising 4.4 Mb/d from 2019 levels to hit 104.1 Mb/d by 2026.

All of this demand expansion relative to 2019 is expected to come from emerging and developing economies, underpinned by increasing populations and incomes. Asian oil demand will continue to rise strongly, albeit at a slower pace than in recent years, forecasts from the IEA show.

A green energy future pivot

Still, a much stronger pivot towards a cleaner, green energy future could hasten peak demand, warned the IEA.

“Further fuel efficiency improvements, increased teleworking and reduced business travel, much stronger electric vehicle penetration and new policies to curb oil use in the power sector and more recycling will all be needed,” added the IEA.

Taken together, these actions could cut oil use by as much as 5.6 Mb/d by 2026, which would mean that oil demand never gets back to pre-crisis levels. However, this seems unlikely, particularly in such a short timeframe.

Most analysts remain optimistic about the recovery in demand in Asia’s two largest oil markets, China and India, which will help bolster global oil prices this decade.

Energy Aspects sees Chinese oil demand expanding by 2.3 Mb/d between 2019 and 2040 – or 0.7% yearly growth – with China forecast to become the world’s biggest oil consumer in the early 2030s. Indian oil demand expansion will outpace China – up by 5.8 Mb/d over the same period – or 3.8% yearly growth.

“We don’t see peak global oil demand until early 2030s. The big supportive influence to ongoing demand growth, over the next decade, is the fact that many emerging markets have yet to consume.

They have such low levels of per capita demand that it is almost impossible to stop these people consuming more oil products as their incomes rise,” Energy Aspects’ Parry told Energy Voice.

The IEA’s business-as-usual scenario calculates that transport in emerging markets makes up more than 80% of all expected growth in oil demand up to 2030, with half that growth forecast to come from India and China alone.

These countries, however, are already taking steps to reduce their dependence on oil, reports the IEA, actively supporting electric vehicles and pushing prices for the non-emitting vehicles close to those of their petrol and diesel counterparts.

China is certainly supporting environmentally friendly alternative forms of transport, but India less so, said Parry. This explains the relatively muted growth rates for China, with Energy Aspects forecasting Chinese oil demand to peak in the late 2020s.

The big challenge for India will be the supporting alternative and environmentally friendly transport infrastructure. Investments in infrastructure need to be made before people buy electric vehicles on-mass, plus India cannot afford the additional subsidy costs, added Parry.

Indian oil demand growth will be key for global markets

Moreover, the trajectory of Indian demand growth, will be key to global oil markets over the next two decades. The South Asian nation is expected to be the world’s fastest growing major oil market thanks to rising incomes and improving standards of living.

Crucially, oil will continue to dominate India’s fast-expanding transport sector. With the IEA projecting Indian energy demand from road transport to more than double over the next two decades.

Over half of the growth is fueled by diesel‐based freight transport. An extra 25 million trucks will be travelling on India’s roads by 2040 as road freight activity triples, and a total of 300 million vehicles of all types are added to India’s fleet between now and then, reported the IEA in its India Energy Outlook 2021.

“Transport has been the fastest‐growing end‐use sector in recent years, and India is set for a huge expansion of transportation infrastructure – from highways, railways and metro lines to airports and ports,” said the IEA.

As a result, India’s oil demand is estimated to rise by almost 4 Mb/d to reach 8.7 Mb/d in 2040, the largest increase of any country. However, if India changes course by pursuing a more sustainable and greener energy development path, including a much stronger push for electrification, efficiency and fuel switching, oil demand growth could be limited to less than 1 Mb/d by 2040, added the IEA.

Such an energy transition would be a massive environmental achievement but seems unrealistic just now. Although the narrative could change in the longer term, especially if higher oil prices drive India, which is highly dependent on imported barrels, towards natural gas and electrification in transport, to improve energy security.

“Based on today’s policy settings, India’s combined import bill for fossil fuels is projected to triple over the next two decades, with oil by far the largest component.

Domestic production of oil and gas continues to fall behind consumption trends and net dependence on imported oil rises above 90% by 2040, up from 75% today. This continued reliance on imported fuels creates vulnerabilities to price cycles and volatility, as well as possible disruptions to supply,” warned the IEA.

Are we entering a new oil supercycle?

Cleary, opinion is divided between the bulls and the bears.

The bull argument focuses mainly on supply, said Neil Beveridge, senior oil analyst at Bernstein. “As oil majors cut investment capex, oil production will decline creating a supply shortfall in the market, where demand tends to be relatively price inelastic.”

“The bear case, on the other hand, focuses on demand. Electrification and hydrogenation of transport (which makes up more than 50% of oil demand) will result in peak oil demand in the next 10 years or according to some, such as BP, may have happened already,” Beveridge wrote in a report Are we entering a new oil super-cycle?

“Intuitively it should be expected that demand drives super-cycles. A key argument as to why there will not be another oil supercycle is that we are close to peak demand. But there is very little evidence from history to show that demand drives super cycles,” said Beveridge.

The 1970s oil supercycle came about after U.S. oil production peaked in 1970. The 2000s super-cycle has been blamed on the rise of China, which was the catalyst for a rally in all commodities. But while China played a role, so did the collapse in non-OPEC supply, added Beveridge.

Supercycles should be accompanied by either low or falling levels of spare capacity, said Beveridge.

With the OPEC+ agreement removing 8 million barrels from the market in response to demand destruction caused by the pandemic, spare capacity is back to 8% – levels last seen in the 1990s. However, Bernstein does not expect this to last a long time. As demand recovers most of the spare OPEC capacity will be absorbed, bringing it back to levels of around 3% of demand, estimates the investment research firm.

US Dollar strength could impact a commodities and oil supercycle

The strength of the U.S. dollar also plays a role in supercycles.

In theory, a weak dollar should support demand, making oil cheaper in non-USD currencies. The 1970s and 2000s super-cycles correlated directly with major falls in dollar strength, said Beveridge.

The dollar has weakened significantly since last May and is expected to continue losing strength against other currencies as the U.S. government keeps inflating its money supply and maintains low interest rate levels.

Looking ahead, there will be strong oil demand growth over the coming years, as a result of the recovery post-pandemic. “On the other hand, lower investment in supply suggests that non-OPEC supply growth will be limited.

In some ways, the decade ahead has some similarities with the 2000s. Industry spare capacity, real GDP growth, a weaker dollar and the relative balance between demand and non-OPEC supply all look similar,” said Beveridge.

Still, “while there are parallels between the 2000s and the coming decade, it feels premature to say a super-cycle is underway. In the next two years, much depends on the strength of the demand from the pandemic and the response from OPEC,” added Beveridge.

It is not yet clear if OPEC will maintain supply discipline or shift back to a strategy of market share maximisation.

But ultimately, Bernstein believes that another bull cycle in oil seems a probable scenario over the decade to come, before peak oil demand arrives.

Oil is not finished yet – triple-digit prices are looming

An almost unbroken increase in the price of oil since the beginning of 2021 came to a crashing halt in the second-half March.

Brent crude fell from just over $70 a barrel in early March to around $60 a barrel by March 24.

This was not unexpected, as something of a disconnect was emerging between the strong pricing in the paper oil futures market, and the more subdued pricing in the physical market, particularly in Asia, Clyde Russell, a commodities analyst at Reuters, wrote on March 1.

Russell nailed it when he predicted “there appears to be a gap between the current bullish pricing of paper crude, and the somewhat more bearish signals of demand from Asia for physical crude for loading in the second quarter.”

All the same, most analysts expect Brent crude prices to average around $60 a barrel this year, give or take a few dollars. While prices may weaken in the second quarter, they are expected to strengthen again in the second half of the year, as economic growth gets back on track post-COVID, particularly in Asia.

The retreat in crude oil prices may dampen speculation of a new bullish cycle. However, several signals point towards prices approaching triple digits.

If U.S. shale production disappoints, as predicted by Goehring & Rozencwajg, and demand remains strong from emerging markets, particularly in Asia, then global oil prices will surely top $100 over the coming years.

Many analysts believe U.S. oil production will rebound and help balance markets. But Saudi Arabia, one of the most powerful forces in global oil markets, is not convinced that U.S. output will bounce back.

Significantly, Saudi Arabia is not afraid that stronger global oil prices will trigger a renaissance in U.S. shale oil output – that would eat into the kingdom’s market share. Perhaps the Saudis, with their vast resources, have a better understanding of the prospects for shale productivity than most oil market analysts.

Certainly, “shale producers – as eventually happens to all commodity producers in a bear market – are finally in that phase of the cycle where it’s not purely about what you can produce.

It’s about what you can produce profitably, and about respect for shareholder capital,” John Stepek wrote in his article “Here’s why Saudi Arabia is no longer worried about shale oil” in Money Week.

In the past, shale companies desperate for cashflow, kept pumping, even at unprofitable prices, to sell something for hard cash. This is not the case anymore, as the big players consolidate the shale field, they do not want to pump barrels at a loss.

Meanwhile, underinvestment in new upstream projects will also squeeze supply. The European supermajors are falling over themselves to shrink their oil and gas portfolios in an effort to slash carbon emissions and prepare for the end of the oil age. They are shifting more capital to renewable energy alternatives such as hydrogen and wind power, at the expense of oil.

Indeed, the world’s top energy companies slashed the value of their oil and gas assets by a record amount last year. Since the fourth quarter 2019, eight international oil companies (IOCs) wiped a record $105 billion off their books and announced plans to lay off up to 40,000 workers, reported the IEA.

“The hefty investment cuts seen in 2020 and supply-chain disruptions due to Covid led to a sharp decline in project approvals last year and delays to many project timelines.

Conventional approvals fell to a multi-decade low in 2020, with projects accounting for only 3 billion barrels given the green light. The postponement of planned project sanctions means that operators may have wiped out over 2 Mb/d of potential supplies by 2026,” said the IEA.

Moreover, the irony about environmental, social, and governance (ESG) worries, particularly relating to climate change concerns, is that the oil sector is being starved of capital. This looks set to accelerate a structural supply deficit and create an energy bull market.

As Grice of Calderwood Capital Research told The Market NZZ “the energy transition is real, but it’s moving at a glacial pace.”

The annual Electric Vehicle Outlook summary by Bloomberg projects that electric vehicles will only make up around 8% of the total fleet of passenger cars by 2030. The number of cars is expected to increase from today’s 1.2 billion vehicles to 1.4 billion, but only about 110 million of them will be electric vehicles.

So, “the number of internal combustion engine vehicles by then will be around 1.3 billion, which implies a forecast rise of around 0.7% per year. Moreover, while passenger vehicles contribute around 60% of the global demand for crude oil, the rest comes from heavy duty vehicles, aviation and the petrochemicals industry for which there are, as yet, few alternatives.

I’m not saying that this is something I’m particularly happy about, but my job is to allocate capital according to the way the world is, not according to the way I want the world to be. Oil will continue to play a central role in the global economy for decades,” said Grice.

Although global demand for oil looks set to peak within the next 10-15 years, the evidence overwhelmingly suggests that oil is far from dead. Price risk for international oil benchmarks remains firmly to the upside with $100 a barrel crude prices a real possibility.

Indeed, oil looks set to have one last hurrah before global demand starts to enter terminal decline. Ironically, triple-digit oil prices will help accelerate the energy transition away from oil and eventually hasten its demise.

But that is a story for another decade.

Recommended for you

© Shutterstock / Pilotsevas

© Shutterstock / Pilotsevas