The liquefied natural gas (LNG) market is primed for a global battle for supply with far-reaching repercussions as the threat of Russia cutting off Europe sends the continent scrambling for alternatives.

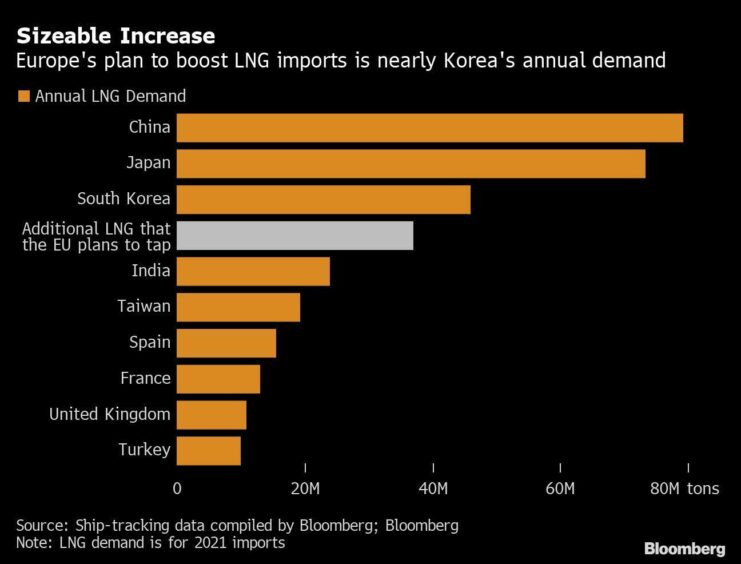

Russia pumps enough gas into Europe every day to cover a third of the continent’s consumption. To replace most of that supply by the end of the year, the bloc drew up a plan that requires new sources of LNG nearly equivalent to annual deliveries to South Korea, the market’s third-largest buyer.

It’s a rerouting of trade flows that would shred the market’s current structure. Global demand would by far outstrip additional LNG supply available this year, causing Europe to steal shipments from Asia’s closest producers and send already eye-watering prices soaring further.

“This would place huge upward pressure on LNG spot prices, as Europe essentially fights with Asian countries over who will avoid destroying demand,” said Saul Kavonic, an energy analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG. “It’s very inefficient to see Australia LNG cargoes head to Europe, but that could happen now as most of the rule book for energy markets has been thrown out the window.”

Sizeable Increase

The fallout from the upheaval could be dramatic, with higher prices and energy supply shortages straining Asian economies, crimping profits and saddling consumers with sky-high electricity bills. Emerging countries that are less able to pay lofty prices such as India and Pakistan stand to suffer the most, while a shift to dirtier fuels could also put nations’ climate targets behind track.

Spot prices of the heating and power plant fuel jumped to a record this week, with the North Asia LNG spot price benchmark reaching nearly $85 per million British thermal units, according to S&P Global Platts. Previously, prices rarely topped $50. While oil’s rally has captivated markets, the increase for gas is even more dramatic — with prices surging to the equivalent of more than $600 per barrel.

“We are expecting spot procurement to all but dry up in Asia due to the high prices,” said Jeff Moore, an analyst at S&P Global Commodity Insights. It’s likely that the benchmark “will trade close to parity with European hub prices, or perhaps even at a slight discount, which is a rare phenomenon given the net-short nature of the Asian market.”

Global natural gas supplies were already tight heading into 2022 due to a lack of new export projects and a post-pandemic rebound in demand. As tensions over Ukraine heated up, North Asia, home to the world’s top LNG buyers, moved to secure supply via long-term contracts, according to traders in the region. The EU’s plan to curb Russian supplies by two-thirds by the end of the year will accelerate Asia’s effort, they said.

Europe plans to diversify its supplies of LNG and is continuing discussions within G7 and with Japan, South Korea, China and India on medium-term partnerships, the European Commission said in a strategy adopted on March 8.

The crisis will cause importer nations to consider their reliance on countries that don’t share the same values, according to Meg O’Neill, chief executive officer of Woodside Petroleum Ltd., which last year approved a $12 billion project in Australia aimed at boosting exports for at least two decades.

“The world is going to have some sober reflection on the pathway to diversify energy supply, and will look to countries like the US and Australia to see how they can support like-minded countries in providing their energy,” she told a Sydney conference Wednesday.

The desired increase in European LNG imports means that global demand will grow by nearly 10% this year. But producers have limited ability to boost supply in the short term. Plus, roughly 65% of the world’s LNG supply is already tied up on long-term contracts, leaving just a sliver for Europe to tap.

Suppliers in the US, Africa and the Middle East will be best placed to send more shipments to Europe, but at the expense of deliveries to Asia, according to Nikos Tsafos, James R. Schlesinger Chair in Energy and Geopolitics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

Europe’s LNG imports surged to a record earlier this year as traders diverted supply from the US and other regions to take advantage of more attractive prices. That won’t be able to continue for much longer, as buyers in Japan and China will soon need to refill inventories drained over the winter.

“Europe will need to bid these cargoes away from Asia,” Tsafos said. “But what does a bidding war look like when spot prices are already above $50? I have no idea.”

Natural gas prices in Europe and Asia surged to a record on Russia supply fears

Some Asian buyers with flexible US supply contracts may choose to send shipments to Europe to take advantage of attractive prices, instead of their home markets, according to BloombergNEF analyst Lujia Cao.

Higher LNG prices and potential shortages mean utilities in countries such as Japan, South Korea and Pakistan — which rely on imported gas to generate a large chunk of electricity — will shift to dirtier alternatives like coal and fuel oil. The impact on climate could be severe, intensifying pollution in Asia and complicating work to meet goals set during the COP26 climate summit in November.

“This will pose a challenge particularly in Asian markets – like in Europe – where gas is seen as a transitional fuel,” said Tom Marzec-Manser, head of gas analytics at commodities researcher ICIS in London. “This mean transition goals may be delayed and become more expensive.”

Perhaps far worse for these governments will be the surging power bills for households and businesses, which will risk lower spending and slower economic recoveries. While North Asia has traditionally been insulated from the spot market by long-term contracts, a shift to short-term supply over the last decade means that costly gas purchases are likely to trickle down to consumers.

China, the world’s top LNG buyer, faces a squeeze on companies’ profits and consumer spending power, as well as slower demand for its exports — complicating Beijing’s effort to stabilise a slowing economy.

The Ukraine war and resulting fuel costs mean that Japan, the world’s second-largest LNG importer, needs about $80 billion in aid to shore up its fragile economy, according to an economic adviser to former premier Shinzo Abe. Higher prices “shift the debate on Japanese energy security in ways not anticipated even six months ago,” said Tobias Harris, senior fellow for Asia at the Center for American Progress think tank.

Biggest Losers

Governments in North Asia and Europe may be able to work together to ensure their nations receive enough supplies. Still, Europe’s plan to boost LNG imports will come at the cost of demand destruction in the emerging world. The biggest losers are poised to be nations in South Asia, like India, Pakistan and Bangladesh, which are much more price sensitive and are unable to procure spot cargoes at current rates.

India is particularly exposed, with LNG imports unlikely to grow in 2022 as importers shun expensive spot cargoes, according to ICIS. Higher fuel prices are eating into disposable incomes of consumers, the backbone of the economy that has yet to fully start spending after the pandemic.

Soaring LNG prices have become a political liability in Pakistan, with the opposition government railing against the current leader for mishandling fuel supplies. European suppliers are even canceling scheduled shipments from long-term contracts to Pakistan, and are unable to secure alternatives for the cash-strapped nation.

“In the best case, this means burning more oil and coal,” said CSIS’s Tsafos. “In the worst, it’s electricity rationing.”

Recommended for you