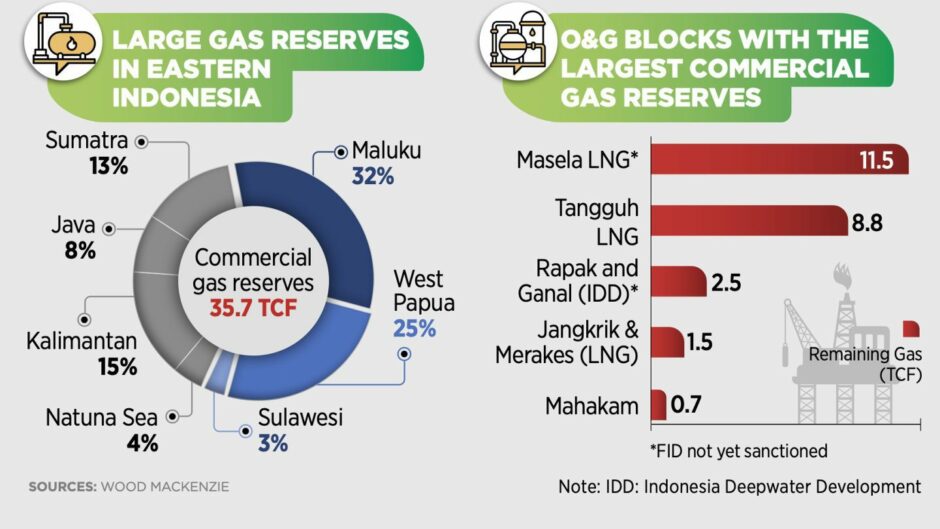

Indonesia has an ambitious target to almost double natural gas production from 6.5 billion cubic feet per day (cf/d) to 12 billion cf/d by 2030. Hitting that goal means giant undeveloped gas projects, such as Inpex’s Masela and Chevron’s IDD, must proceed rapidly.

The trouble is these projects have stalled in recent years, largely because of political meddling, as well as the rising trend towards resource nationalism under President Joko Widodo’s watch since he took power in October 2014.

Dwi Soetijpto, the head of Indonesia’s upstream regulator SKK Migas, is under pressure from Widodo, known locally as Jokowi, to get Masela and the Indonesian Deepwater Development (IDD) moving. This explains the pronouncements, suggesting progress on these mega projects, by Dwi and other senior officials, to delegates and the media at the Indonesian Petroleum Association (IPA) conference last week in Jakarta.

Japan’s Inpex (TYO:1605), which leads Masela, will submit yet another revised plan of development by the end of the year. At the same time, an Indonesian consortium led by Pertamina is being steered by Jokowi to buy Shell’s (LON:SHEL) 35% share of Masela. Shell’s desire to divest – triggered by Jokowi’s previous decision in 2016 to cancel a government-approved plan of development for FLNG at the block – has been an impediment for the project.

Dwi reckons Inpex will take a final investment decision (FID) by end of 2023, while Inpex has said FID is expected in the second half of the 2020s. Inpex’s forecast is more realistic, as a new plan of development needs to be hammered out with the government. And, crucially, a tricky divestment – that involves Japanese-backed loans and various Indonesian stakeholders – needs to be negotiated with Shell.

Chevron Divestment

Meanwhile, if Dwi is to be believed, Italy’s Eni (MIL:ENI) is close to buying out Chevron (NYSE:CVX) from the IDD project. The US giant put its 62% share of IDD up for sale three years ago after failing to agree attractive terms and conditions with the Indonesian government that would allow the development to compete for investment capital within Chevron’s global portfolio.

But market sources suggest the government is again jumping the gun with its pronouncements. It is true that Eni would be the logical buyer. The Italian company, which already operates fields nearby in the Kutei basin, is currently a minority shareholder in the IDD with a 20% interest, along with China’s Sinopec, which holds the remaining 18% share.

Presumably, if Dwi is correct, Eni will increase its stake, but the Italian company is unlikely to operate the IDD with an 82% interest. No doubt Pertamina will be offered a stake in the project and Sinopec might need to be persuaded to boost its shareholding. UK-based Neptune Energy, a partner of Eni, could also be in the mix too.

Still, sources suggest there is no urgency to finalise the sale of IDD. There are interested buyers and discussions are making progress. However, all parties share the mantra that a “bad deal is worse than no deal” and a final agreement seems someway off just now.

A successful divestment deal would see Chevron, previously one of Indonesia’s largest oil and gas investors, left with no operated-upstream assets in the country after it handed the giant Rokan Block to Pertamina last year. Chevron’s request to extend their Rokan PSC was refused in July 2018 in favour of Pertamina as part of Jokowi’s resource nationalism drive to hand legacy production to the national oil company.

Downsizing

As Chevron downsized its operations the supermajor vacated four of its five office floors in a Jakarta building. Inpex, which shared the same building, took over all the space vacated by Chevron, presumably to beef up its Masela project resources. Ironically, the Japanese company has now returned it all and keeps only one floor in the office tower. This would fit with the waning enthusiasm from Tokyo for the proposed Abadi liquefied natural gas (LNG) project in the Masela Block in recent times.

Still, there is a glimmer of hope for Masela. The war in Ukraine has put energy security top of the agenda within the Japanese government and Prime Minister Fumio Kishida appears to be putting his weight behind Jokowi’s drive to revive the project.

Jokowi, whose final presidential term ends in 2024, will “move mountains to make Masela happen” as part of his closing legacy before leaving office, noted a senior industry executive. Pertamina will be pushed to buy Shell out of the project and Inpex could find itself in a good position to negotiate favourable commercial terms and conditions with the Indonesian government.

Elsewhere, the BP-led Tangguh LNG project reported record gas production from trains one and two in September. Its long-delayed expansion project that will add a third train is also due to come online in 2023, which will provide a welcome boost for Indonesia’s upstream. But hitting the 2030 gas production target still looks like a stretch just now without urgent radical action.

© Supplied by IPA

© Supplied by IPA