Even by Shetland’s terms, January 5 30 years ago was a wild night of weather.

The hurricane roared relentlessly and mercilessly, so that when islanders awoke, it was to the news they most dreaded.

An oil tanker had gone aground at Garths Ness and light crude was flowing from it.

The toll on the islands and their wildlife was potentially catastrophic.

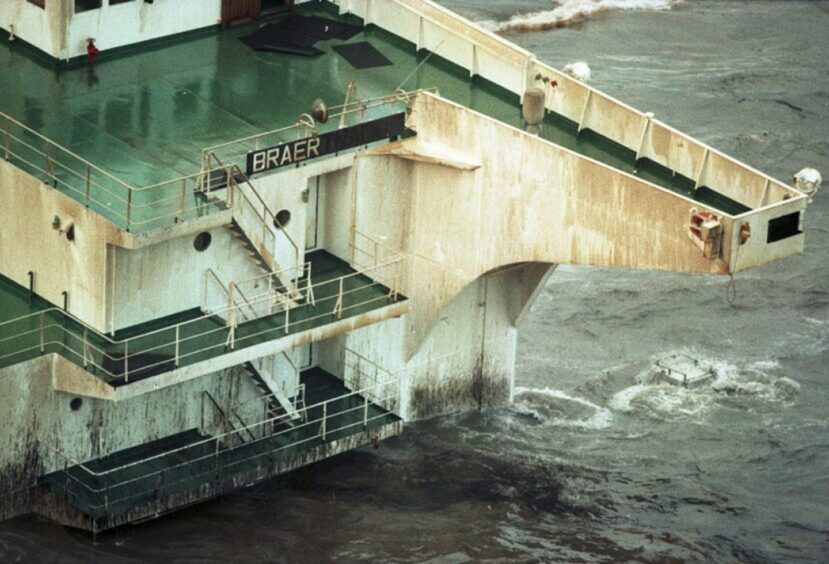

The drama had begun unfolding two days earlier, when the Canadian-registered tanker Braer, en-route from Bergen to Quebec, had lost engine power some five nautical miles south of Sumburgh Head.

Sea water had contaminated the ship’s heavy fuel after pipelines on deck broke loose, allowing seawater to enter the vessel’s bunker tanks via broken air vents.

In the teeth of the hurricane, the loss of power caused the crew to lose control of the ship.

The first Lerwick coastguard heard of the impending disaster was shortly after 5am on January 5.

They were told that the Braer, stocked with 85,000 tonnes of Norwegian Gullfaks crude oil, was drifting south-westerly but was in no immediate danger.

Rescue helicopters

The coastguard alerted rescue helicopters from Sumburgh and RAF Lossiemouth, and the Braer’s master, Alexandros S. Gelis agreed that non-essential personnel should be taken off the ship.

By 8.25am, in a heroic effort, the coastguard helicopter from Sumburgh had airlifted 14 out of the 34 strong crew to safety.

Captain Gelis feared the ship would run aground near Horse Holm island, and might burst into flames.

He issued orders to abandon ship.

He hadn’t taken the strong local currents into account.

They drove the ship against the prevailing wind, missing Horse Holm and drifting towards Quendale Bay.

Meanwhile the anchor-handling vessel Star Sirius arrived on the scene and it was decided to try to establish a tow.

Gelis and some of the crew were helicoptered back on board the ship, but efforts to attach a tow line were unsuccessful.

The Braer grounded at Garths Ness, losing oil from the moment of impact, and the would-be rescue team were helicoptered back off the vessel.

The news spread around the world, and with it talk of a massive environmental disaster playing out on the pristine Shetland islands.

A Joint Response Centre was set up with the relevant marine pollution and emergencies operations and various UK ministries working alongside local councillors, managers, environmentalists and technicians.

Quendale beach was closed off amid fears the tanker might explode, and 23,000 sheep were removed from the area.

By Day Two aircraft monitoring the spread of the oil were granted permission to spray chemical dispersants over it.

At this point, the Greenpeace ship Solo arrived with facilities to help wildlife affected by the oil spill.

There was some comfort to be taken when it emerged that the spilled oil was lighter, more easily dispersible and more biodegradable than other North Sea crude oils.

It was already dispersing by wave action and evaporation, preventing worse impact on the shore.

Command Centre

Shetland had long prepared for oil spillages, and multiple agencies came together to create a wildlife response command centre at the Boddam scout hut.

With massive volunteer turnout, they walked the beaches twice a day, collecting oiled birds and other animals.

Live wildlife was treated, while those which had perished were recorded and stored.

The work was concentrated in the south-west mainland from Sandwick to Maywick, but the oil was spreading northwards.

A week later, work was going on from Burra, Scalloway, Whiteness and Weisdale to Culswick in the west.

A further command post was set up at Holmsgarth to survey the northern coasts.

It was a monumental effort, with so much at stake for Shetlanders dependent on agriculture and tourism.

They said you could smell the hydrocarbons in the air 25 miles away in Lerwick.

Over the next week, the battering of the storm and the tides ground the Braer against the rocks until it split in two.

All the oil on board escaped.

Environmental toll after Braer disaster

More than 1,500 seabirds died.

More than 200 oiled birds were brought in for rescue, but it’s probable thousands were impacted.

The ratio of dead to injured birds was almost 10-1.

Quendale Bay was home to 2,000 birds including shags, long tail and eider ducks, black guillemots and great northern divers.

Clogged with oil

Some were humanely killed as thick oil enveloped their feathers, leaving them with no realistic hope of survival

Grey seals were found in respiratory distress due to volatile compounds from the oil, and some local people also reported breathing problems.

By the end of January, very few oiled birds were being washed up, and by April 1993 the temporary ban on fishing was lifted.

It’s considered the landward effects were minimal, confined to a 30ft strip between Garths Wick and Garths Ness.

Ecological steering group

Three weeks later the focus shifted from wildlife rescue to the creation of an ecological steering group working on human health, economic and ecological issues.

They reported in 1994 that all was well with farmed salmon after the disaster. They showed no taint and the sediment under the cages was stable.

There were low levels of shellfish contamination and, crucially, change in the sand eel populations.

Some of the lowest level organisms such as worms and invertebrates were affected but not significantly.

The steering group concluded that although there were local and limited adverse effects, the overall impact of the spill had been minimal.

What happened to the Braer?

The wreck was designated dangerous because of the presence of oil until October 1994.

In its exposed position it broke apart and sank, although its upturned bow could be seen for seven years before finally sinking.

The coast is so exposed that the wreckage was smashed flat in less than 30ft of water, with little recognisable remaining.

The vessel had been built in 1975 in Japan, and didn’t have the more modern double hull which would have lessened the chance of an oil spillage.

The most blame was apportioned to the weather, but also attributed to Alexandros Gelis showing a fundamental lack of seamanship.

The captain later said he had tried desperately to get his crew back on board but the police wouldn’t release them due to confusion over orders.

Compensation

By October 1995 a total of £45m had been paid out in compensation but a moratorium on payments was then imposed as the International Oil Pollution Fund neared its limit of £50m.

© Gerry Penny/EPA/Shutterstock

© Gerry Penny/EPA/Shutterstock © PA

© PA © Supplied by DCT

© Supplied by DCT © Gerry Penny/EPA/Shutterstock

© Gerry Penny/EPA/Shutterstock © Supplied by DCTMedia

© Supplied by DCTMedia © Shutterstock

© Shutterstock