Asian nations counting on offshore wind farms to meet clean energy goals are facing an increasing shortage of ships for installing the massive turbines in the sea.

As countries embark on a rapid build-out of wind power in the next decade, builders can’t churn out the support vessels fast enough to keep up, shipping experts say. The situation is only going to get worse as blades get longer and require bigger ships to handle them.

“Specialised vessels are going to be in demand for projects in Taiwan and South Korea,” said Sean Lee, chief executive officer of shipyard Marco Polo Marine Ltd. “There will be more and more projects coming up, and a big wave of them in Japan from 2028.”

The complicated job of planting a wind turbine in the seabed requires several types of ships specially designed for the work. Turbine installers feature massive cranes capable of hoisting objects weighing as much as the largest sequoia tree. Commissioning service operation vessels, or CSOVs, provide adjustable gangways that allow technicians to reach the turbine blades.

Excluding China, there are currently only about 10 turbine installing ships and a few dozen CSOVs operating worldwide, according to shipbroker Clarksons. By 2030, demand for turbine installers will outpace supply by about 15 vessels, while the gap for CSOVs will widen to more than 145 CSOVs from 30 currently, it estimates.

China has 84 ships capable of installing wind turbines, according to trade group Global Wind Energy Council. But the majority of those can only handle small turbines, with many having been converted from oil and gas ships. These are unlikely to meet specifications in Europe or elsewhere in Asia.

The global floating offshore wind market is expected to increase to a cumulative 27.6 gigawatts by 2035 from just 0.1 gigawatt currently installed, according to BloombergNEF. While that represents tremendous growth, the sector must resolve supply chain and other issues, BNEF said.

“If new investment in offshore wind vessels is delayed, then it could affect development time lines for wind farms globally,” said Luisa Amorim, an analyst at BNEF. “The current global vessel supply is insufficient to meet the demand for installation vessels for both offshore wind turbines and bottom-fixed foundations.”

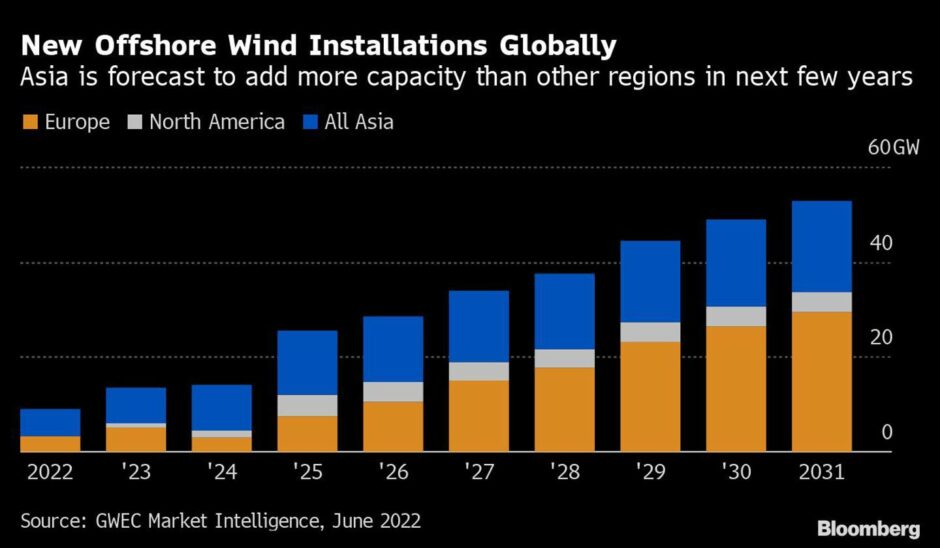

The shortage of ships is significant for Asia as the GWEC predicts the continent will top Europe as the region with the most new offshore wind installations through 2026. A lack of vessels could set back countries’ efforts to diversify away from fossil fuels.

“The potential crunch is likely to occur in the mid-to-late 2020s as more countries begin constructing their wind farms to meet 2030 national targets,” said Bahzad Ayoub, a senior analyst at consultant Westwood Global Energy Group.

Many of the existing ships have been deployed to Europe, said Marco Polo’s Lee. To fill the gap in Asia, tugs and support vessels that were serving oil rigs in Southeast Asia have been diverted to wind farms, he said.

But using oil and gas ships can’t be a long-term solution, and the current fleet of installation vessels may soon become obsolete as turbine sizes grow to be almost as long as the Eiffel Tower.

The world’s largest floating wind project, in Norway, uses turbines with a rotor diameter of more than 160 meters. As technology advances, future wind farms could see these lengths increase to 275 meters by 2030, according to the GWEC.

Larger turbines mean the required lifting heights and crane capacities of vessels installing the blades must increase, said Westwood’s Ayoub.

Shipping companies are racing to fill the gap. Marco Polo is building a CSOV by next year to be chartered by Vestas Wind Systems A/S in Taiwan. Cadeler A/S has ordered four turbine installation vessels for 2024-2026 from Cosco Heavy Industries, while Maersk Supply Service has ordered one from Sembcorp Marine Ltd. for delivery to the US in 2025.

“It’s a lot of work to do,” said Lee. “It’s a new industry and everybody’s talking about renewables.”

Recommended for you

© Bloomberg

© Bloomberg