Despite record cash generation, supermajors are investing $100bn less in upstream capex than a decade ago as low-cost, low-emissions projects take priority.

Analysis by Westwood Global Energy shows oil and gas giants BP (LON:BP), Chevron, ExxonMobil (NYSE:XOM), Shell (LON:SHEL) and TotalEnergies are producing less oil and gas but generating more cash than in 2013, despite a similar price environment.

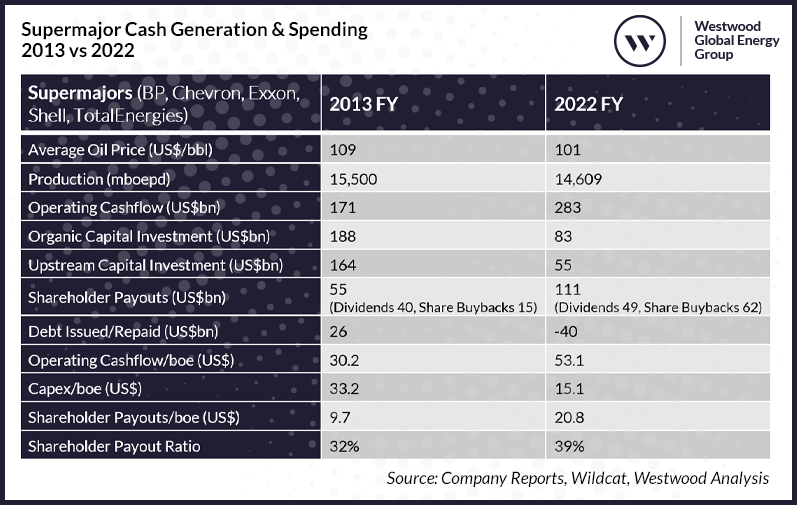

Senior associate Keith Myers notes that production fell by around 900,000 barrels of oil equivalent per day (boepd) between 2013 and 2022, yet operating cashflow increased from US$171bn to US$283bn over the same period.

The production loss is largely due to the divestment of Russian assets, and the shedding of higher cost production during the intervening years. Meanwhile efficiency investments, recent higher gas prices and leaner organisations have allowed the cohort to generate more cash with less input.

Some of the trend is also due to rationalisation. “The oil price crashed in late 2014, exposing the overspend in the dash for growth in the 2010-14 period and massive capital impairments and headline losses followed. Boards shied away from growth to focus on returns,” Mr Myers writes.

Cut to last year, when spiking commodity prices then led to “incredible cash generation” by the newly streamlined firms.

Yet of the $283bn generated last year, just 29 cents on every dollar was reinvested, only 19 cents of which went to upstream investment.

All in all, the decade has seen the group’s upstream capital expenditure plummet from $164bn in 2013 to just $55bn last year.

“Lower supply chain costs mean less capital is needed to sustain production than in 2013, but nonetheless, there is clearly the financial capacity to spend more if companies choose to do so,” he adds.

Meanwhile shareholder payouts have doubled, from $55bn to $111bn last year, with almost all the increase coming in the form of share buybacks.

It’s this situation which is already attracting ire from politicians and some shareholders.

“The modest capital investment levels compared to shareholder distributions has attracted political attention at a time of high inflation when governments in Europe are having to subsidise energy bills. The clamour for windfall taxes to capture the exceptional profits has proved hard to resist,” Mr Myers continues.

Capex steady to 2030

He suggests this focus on “value over volume” is set to continue with capex budgets set to remain at current levels through to 2030, as the supermajors focus on “low cost, lower emissions production” which can generate high margins of cash to enable “generous shareholder distributions.”

ExxonMobil, he notes intends to commit 90% of its capex budget to projects that deliver returns of 10% or greater at less than or equal to $35 per barrel, while TotalEnergies will target $30 per barrel after tax breakeven.

Meanwhile, limited exploration prospects have meant there are fewer opportunities towards which capital could be directed.

Energy transition spending is also increasing but remains “relatively modest” compared to oil and gas. This may also relate to returns; Westwood notes that BP’s reported rates of return from renewable power is typically 6-8%, compared with 20% from hydrocarbons and even more from upstream.

Meanwhile, he says society is calling for both higher oil and gas production in the short term and greater investments in renewables to calm energy prices – something the supermajors are unlikely to respond to.

“It is a combination of continued demand growth for oil and gas and lower investment, which has driven prices higher. Oil companies can say very reasonably that they do not set oil and gas prices; the supermajors together account for only 8% of global oil and 10% of global gas production,” Mr Myers notes.

“Big oil is not going to open the capital investment taps – it is not in their interests to do so.

“Unless it can tame demand to bring prices down, Society will need to decide what do about the excess upstream cash generation. No doubt the debate about windfall taxes will continue.”

Recommended for you

© Westwood Global Energy

© Westwood Global Energy