Plunging margins for petrochemicals are set to take a bite out of Big Oil’s quarterly profits, adding to the pain companies are feeling from lower oil and gas prices.

Sluggish demand for consumer goods that use plastics and rubber, combined with a flood of new factories in the US and China, means margins face a potentially protracted downturn.

The slump, which the CEO of Cologne-based Lanxness AG called a “Lehman 2” moment for the chemicals industry, has cast a dark cloud over a sector long-touted as the future for Big Oil. Demand for fossil fuels is forecast to peak in the coming years due to the fight against climate change, leaving petrochemicals as the companies’ main growth engine.

Over the past five years, Exxon Mobil, Shell, and TotalEnergies have invested heavily in US plants that turn cheap gas feedstocks unleashed by the shale boom into the building blocks for everything from electronics to building materials to household appliances.

“It’s been a pretty dramatic downturn,” said Joseph Chang, a New York-based analyst at ICIS, an industry consultant and data provider. “With chemicals oversupplied right now, large oil companies will find other areas to invest in.”

Big Oil may be insulated from the worst of the bloodbath because it’s still a relatively small part of their global oil and gas operations. On Sunday, Chevron posted better-than-expected earnings as output in the Permian Basin of Texas and New Mexico soared to a record.

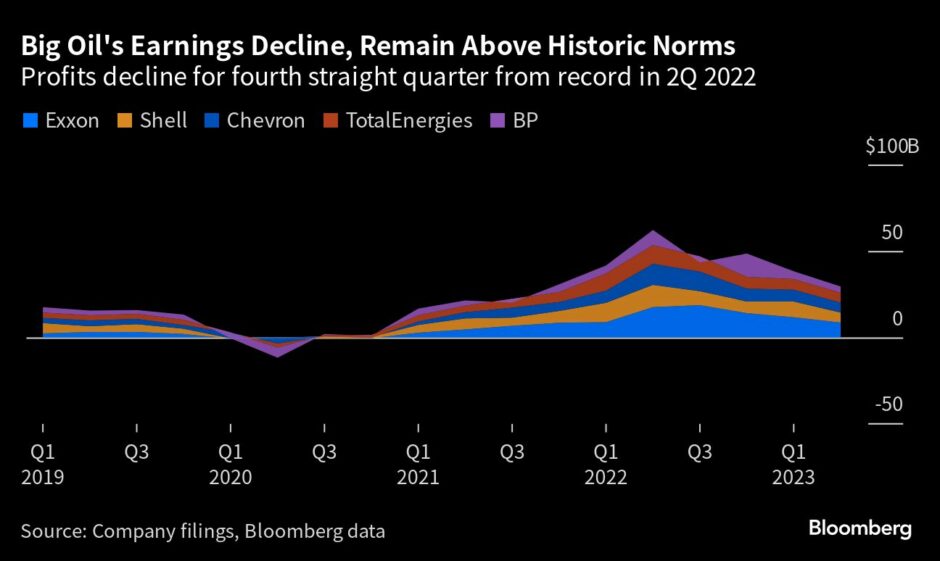

But a structural deterioration in chemicals adds to headwinds already facing crude, trading and refining markets. While Chevron’s adjusted earnings were higher than analysts expected, net income dropped to $6 billion, the fourth decline in a row. The company also said it waived the mandatory retirement age for Chief Executive Officer Mike Wirth.

Overall earnings for Exxon, Shell, TotalEnergies and BP Plc will likely fall for a second straight quarter, mainly driven by lower oil and gas prices, as well as refining margins, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Still, the oil majors’ balance sheets remain “healthy”, mostly with low debt and surplus cash, RBC analyst Biraj Borkhataria said. But if commodity prices move lower, so could shareholder returns next year, he said.

Analysts have been trimming estimates for Exxon and Shell since they released guidance earlier this month that warned of lower refining and trading earnings. In particular, Shell said its gas trading division — which boosted the company’s profits to historical highs earlier this year — will fall back in line to average levels.

With those statements largely priced in — and oil already rebounding early in the third quarter — the potential for prolonged weakness in the often-overlooked petrochemical market is becoming a pressing concern.

Petrochemicals play two vital roles in Big Oil’s operations. They’re a hedge when oil and gas prices drop. And they offer growth rates forecast to eventually eclipse crude demand, which many analysts project will plateau or decline in the decade ahead as nations push to phase out fossil fuels.

Exxon and Shell started up giant chemical plants in Texas and Pennsylvania last year, producing plastics like polyethylene and polypropylene, for which there are few green alternatives.

The short-term outlook is challenging: Exxon and Shell aren’t the only ones vying for a piece of the petrochemical pie.

Some 49.5 million tons of new ethylene capacity has or will come online globally from 2020 to 2024, outstripping projected demand by 55%, according to S&P Global. More than half is coming from China, which wants to reduce imports of chemicals key to its manufacturing industry, the world’s biggest.

And there’s more to come. At least a dozen giant new facilities are being built or are due to start construction over the next four years, with an additional 9.5 million tons coming online from 2025 to 2030. Three new plants in the US and Canada will increase North American polyethylene production by 13% this year alone, according to ICIS.

Demand is failing to keep up. High interest rates are weakening economic growth. Many consumers who are spending are opting to travel, go to restaurants or take other outings instead of buying durable goods, Chang said. A weaker-than-expected Chinese recovery and lower usage of disposable masks and medical equipment related to Covid-19 is also weighing on the sector.

Chemical producers including FMC Corp., Ashland Inc. and Olin Corp. have warned of substantially lower profits for the rest of this year.

Still, Big Oil is far from being in crisis mode. Combined earnings of Exxon, Shell, Chevron, TotalEnergies and BP will be $29.5 billion in the second quarter. That’s 23% lower than first three months of the year but still more than double the quarterly average from 2015 to 2019, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

With lower earnings this quarter, all five companies will face questions about whether they can maintain the generous promises made last year when profits soared to record highs to reward shareholders with big dividends and buybacks.

Lower earnings will “inevitably have a negative impact on distributions” for the European majors who linked their shareholder return targets to cash flow, Kim Fustier, a London-based analyst at HSBC Holdings, wrote in a note.

But Exxon and Chevron should be able to “sustain current buybacks for longer” due to their lower debt ratios, she said.

“We believe the bottom is now in for oil majors’ profits,” Fustier said. “Cash flows should stabilize from 2Q onwards at a high level.”

Recommended for you

© Source: Company filings, Bloombe

© Source: Company filings, Bloombe