A new report finds oil and gas firms are redeploying less capital than in previous years, in favour of upping returns to shareholders.

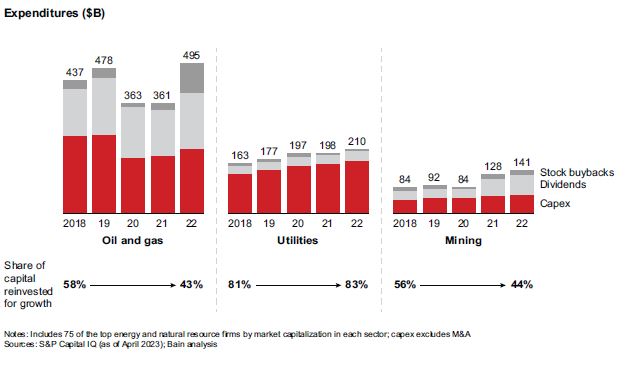

Bain & Company finds that in the oil and gas sector around 43% of capital was reinvested for growth in 2022 – a sharp fall from the 58% seen in 2018.

That is despite the pool of available capital growing, from $437bn in 2018 to just shy of $500bn last year.

Meanwhile it found that utilities are increasing their capex rates, but not yet at a sufficient rate to fully modernize and expand grid networks for the required levels of renewable energy and electrification.

The findings, published in the firm’s Global Energy and Natural Resources report, are based on discussions with clients and a survey of more than 600 executives across the energy and natural resource sector earlier this year 2023.

Bain & Co notes that although the world’s committed investments fall far short of the annual capital required to reach net zero by 2050, it is not capital which is the constraining factor in the energy transition.

“It’s available in most energy and natural resource industries, but instead of being reinvested into low-carbon growth areas, an increasing percentage is being returned to shareholders,” the authors note.

It follows a surge in dividends and buybacks amongst supermajors in the last year, and has persisited in recent months, even as falling commodity prices see profits recede.

The report reveals that only 19% of energy and natural resource executives surveyed see capital scarcity as a barrier to scaling up low-carbon businesses. Their primary concerns are return on investment and customer willingness to pay, with 78% of executives selecting this as a top barrier to decarbonization.

“Energy transition ambitions demand record-setting investment in many sectors, and so far, capital expenditure is significantly lagging,” said Joe Scalise, global head of Bain & Company’s Energy and Natural Resources practice.

“Far from this being an issue of ‘dry powder’ or capital availability, it’s an issue of customer value, willingness to pay, and the ability of policymakers and regulators to set the rules of the game to generate sufficient returns.”

Few incentives to invest

Assuming a 10% average cost of capital, Bain’s report suggests that every $1 billion in capital deployed requires about $160m in revenue from customers each year.

But while consumers are concerned about climate change, they may not be willing to pay higher bills to help address it.

Amid this the authors found “limited incentive” to grow supply or infrastructure to make supply and demand meet across various portions of the energy and mining sector, and a difficulty in maintaining acceptable returns even if investments are made.

“This makes economic returns a first-order scarcity, and locating and capturing them will be a primary challenge of the transition,” the report finds.

“Without enough customers willing to pay (or regulations driving them to do so, as is the case in Europe, where industrial consumers are subject to a carbon cap-and-trade program), the only other major source of funding would be governments (taxpayers). This could take the form of taxing alternatives, subsidies that alleviate the cost of production, or direct funding.”

However, this is not true across the board, with some regional differences identified.

Notably, the report finds that almost twice as many European oil and gas executives blamed policy uncertainty for delayed investment decisions, compared with the previous year (61% vs. 36% in 2022), while fewer executives in North America assigned similar blame (50% vs. 59%) – a discrepancy it suggests could be related to the Biden administration’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA).

It follows more than a year of strife from the UK oil and gas sector in the wake of the Government’s Energy Profits Levy (EPL), which firms have blamed for a wave of project deferrals, cancellations and job cuts.

Supply chain under further pressure

At the same time, meeting the infrastructural demands of net zero could also “push supply chain capacity beyond the breaking point” Bain’s report notes.

The US, for example, would need to more than double its energy transmission capacity, which has grown at about 1% per year to achieve the full potential of the IRA; to meet a 1.5-degree warming target meanwhile, transmission growth would have to increase to between 5% and 6%.

With this in mind, Bain & Co also warned that energy executives may be “overconfident” in their ability to manage the physical impacts of climate change.

Nearly all surveyed said they were “very or somewhat confident” in their ability to manage those risks, but given the severity of this year’s disruptions – from floods to fires – this may be overestimated.

The report indicates people often fail to accurately assess the magnitude and likelihood of rare events, such as the physical effects of climate change, since most have not experienced them firsthand.

It warns that ignoring such high-risk scenarios is increasingly “a short-sighted strategy.”

Recommended for you

© Bain & Co

© Bain & Co