Achieving even modest levels of Diversity and inclusion or, full out, Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, today in the developed world has been a hard-fought battle, is far from completed and is unlikely to ever get any easier.

Imagine the situation in Africa with its population of 1.5billion; a continent so large that it can easily guzzle North America, China, India and Europe with room to spare; and where, out of the 160million child labourers worldwide, more than 70million are African.

Then add the low-carbon energy revolution that is supposed to deliver a sustainable future but which instead is wreaking its own environmental havoc and threatening to make the threadbare existence of millions of Africans even worse than it already is.

Their world has become a critical mineral “klondike”, especially for cobalt and lithium.

DRC (Democratic Republic of the Congo) is the world’s largest producer of mined cobalt, accounting for 70% of global production of which most is gobbled up by the Chinese for car rechargeable battery manufacture.

Then there’s Zimbabwe, Africa’s linchpin miner of Lithium. Often called “white gold,” it is essential for producing solar panels and electric vehicle batteries.

Africa could supply a fifth of the world’s lithium needs by 2030. The Chinese already run most of the country’s mines and are also the biggest customer.

Globally, and according to the latest data from the US Department of Labor’s Bureau of International Labor Affairs (ILAB), child labour is utilised in the mining of 17 critical minerals from 35 countries.

They are: amber, coal, cobalt, copper, diamonds, fluorspar, gold, gypsum, iron, mica, polysilicon, silver, tantalum/coltan, tin, trona, tungsten, and zinc. Most are important to the energy transition.

Of the 35 countries, Angola, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, the Central African Republic, DRC, Ethiopia, Ghana, Guinea, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda and Zimbabwe are African states.

ILAB is succinct: “Sources estimate that at least half of all cobalt ends up in rechargeable batteries. This creates enormous labour risks for the electronics industry, electric vehicle supply chains, and other goods that depend on lithium-ion batteries.

“The spotlight is growing brighter on where and how companies source raw materials like cobalt that are needed to achieve a green future.”

Seeking to solve human poverty has been a core remit of the United Nations; ever since it started out as the League of Nations in 1919, transitioning to the UN from 1946.

There have been many resolutions around the theme of child poverty, labour and slavery. Perhaps the latest relevant to D&I/ED&I was the declaration that 2021 would be the International Year for the Elimination of Child Labour. A key catalyst was the Covid pandemic.

It would lead to the Fifth Global Conference on Child Labour (VGC) being staged in South Africa in 2022. There, delegates vowed to end child labour in all its forms by 2025 and forced labour, human trafficking and modern slavery by 2030.

They agreed on the Durban Call to Action with its six commitments.

Of these, two stand out:

- Strengthen the prevention and elimination of child labour, including its worst forms, forced labour, modern slavery and trafficking in persons, and the protection of survivors through data-driven and survivor-informed policy and programmatic responses.

- Realize children’s right to education and ensure universal access to free, compulsory, quality, equitable and inclusive education and training.

Meanwhile, the ILO (International Labour Organisation) with the African Union (AU) are trying to get meaningful discussions and action to empower African countries in collecting, processing, and analysing child labour data and domestic work statistics.

Participants from national statistical offices of 24 English-speaking African countries are supposed to discuss and identify solutions, as well as prioritise future actions within their respective nations.

It’s October 2023 already; there’s not a hope of eliminating child labour in barely two years, whether in mining or agriculture or anything.

While that deadline will be missed by a mile, late last year Zimbabwe made a declaration that just might help the pendulum shift in favour of the elimination of child labour.

Last December, Zimbabwe, which has Africa’s largest lithium reserves, imposed a ban on raw lithium ore exports, requiring companies to set up plants in the country and process ore into concentrates before export in order to boost local jobs and revenue.

Those seeking to export and not process domestically would need to provide proof of exceptional circumstances and receive written permission to export raw lithium ore.

Zimbabwe’s ban under its Base Minerals Export Control Order (2023) is designed to stop the flight of $billions in mineral proceeds to foreign locations.

Namibia has followed suit, also implementing critical minerals export controls.

But this is fully 10 years after the DRC also implemented critical minerals export controls though there have since been many waivers.

But what is the relevance of this to the child labour/slavery crisis?

According to ESI Africa, traditionally, “mining companies after extraction enjoy all the benefits [while] leaving communities in their catchment areas to bear the brunt of life-threatening dangers associated with their operations”. ESI Africa warns it is time to stop that practice”.

But in the case of China and the Zimbabwe declaration, it is said that Chinese interests are well placed to reap benefits because several Chinese-owned companies have recently completed processing plants in the country.

Indeed Chinese companies have spent over $1 billion acquiring and developing lithium projects in Zimbabwe, which in contrast has seen very little Western investment.

Surely this conjures up a ruthless image as the Chinese are widely regarded as tough business people and not averse to exploitation either including children.

After all, UN records tell us that 7.74% of children were working in China in 2010. However, child labour in this vast country has in fact fallen by 38% since, which suggests that the Chinese are making progress in reducing child labour at home and could perhaps be persuaded disposed of that way in a country such as Zimbabwe.

Perhaps it’s too much to hope for.

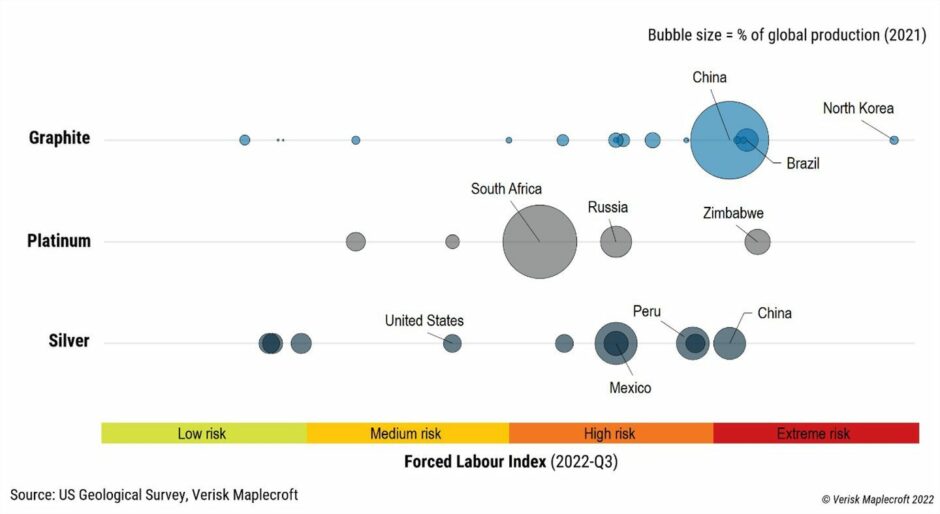

Enter analysts at Verisk Maplecroft (and aside from the ILA listing) who say there are other less-heralded, energy transition materials, the extractors of which also use forced labour including children.

Take graphite, the dominant anode material in commercial lithium-ion batteries.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), the electric vehicle and low-carbon energy sectors will demand 25 times more graphite per year by 2040.

And yet, any optimism around graphite’s association with ‘clean’ energy is dampened by its proximity to human rights abuses.

“More than 97% of graphite production takes place in countries rated high or extreme risk in the latest edition of our Forced Labour Index (FLI),” said Verisk Maplecroft.

“This is primarily a result of the human rights risks associated with the world’s top graphite producing country – China (responsible for 79% of global output).”

Verisk Maplecroft says it is a similar story for platinum, which may play a vital role in the low-carbon economy should the production of green hydrogen and hydrogen fuel cells reach their full potential.

South Africa (responsible for 70% of global production) is rated high risk on the FLI, driven in part by evidence of forced labour in the country’s mining sector. Neighbouring Zimbabwe, which produces 8% of the world’s graphite, is rated extreme risk.

“Two-thirds of the world’s silver, which plays a key role in clean energy through its use as a conductor within solar panels, is produced in countries rated high or extreme risk for forced labour. This includes the world’s largest producer, Mexico (responsible for 23% of global output), as well as Peru (14%) and China (13%).”

However, large mining operators apparently adhere to Mexico’s domestic legal framework and international standards to prevent association with abuses, despite the country’s weaknesses in their implementation.

Verisk Maplecroft’s view is that the risk of forced labour entering minerals value chains cannot be ruled out, particularly via small projects and artisanal mining.

Its analysts warn: “But unless inherent forced labour risks are addressed within key producing countries, the green transition will become increasingly polluted, in turn leaving corporates and investors exposed to material damages stemming from a growing list of human rights due diligence laws.”

Something has to happen and soon to definitively solve the child labour in Africa and elsewhere.

Witness a recent comment made by Harvard academic Siddharth Kara who this year published the book Red Cobalt. It is a harsh indictment of the situation in the DRC and serves as a warning to all African countries utilising forced labour, especially children.

“Imagine an entire population of people who cannot survive without scrounging in hazardous conditions for a dollar or two a day. There is no alternative there. The mines have taken over everything.”

© Supplied by US ITC Dataweb and U

© Supplied by US ITC Dataweb and U © Supplied by US Geological Survey

© Supplied by US Geological Survey