The approval of Equinor and Ithaca Energy’s controversial Rosebank oilfield in the West of Shetland has sparked debate around the UK’s demand for the substance and the benefits of producing it domestically.

The Department for Energy Security and Net Zero said non-energy oil uses cover 10% of UK demand, including feedstocks for a whole range of products and chemicals.

Meanwhile, transport remains the big one for energy, covering more than 70% of demand.

This prompts the question; how much oil is in UK homes and how reliant is the country on this increasingly controversial hydrocarbon?

The oil debate

In the wake of the NSTA approving the Rosebank oilfield, there has been discussion surrounding the demand for hydrocarbons in the UK.

Equinor and Ithaca Energy got the green light for the UK’s largest untapped oilfield last week, however, opponents highlighted that the majority of the hydrocarbons produced will be shipped to overseas refineries and therefore will not impact energy security.

However the UK remains a net importer on oil, particularly from European refineries where Rosebank oil is expected to go.

That’s not only for energy but also for everyday products – so industry commentators argue the demand for the substance must be lowered before production decreases.

Just one day before the North Sea Transition Authority (NSTA) signed off on the west of Shetland development the International Energy Agency (IEA) said that “no new long-lead-time upstream oil and gas projects are needed” to reach net zero.

Given the fact that Rosebank is set to produce until 2051, the development definitely falls under the “long lead” category outlined by the IEA.

When asked about this assessment trade body Offshore Energies UK’s Ross Dornan, said: “The IEA scenario doesn’t consider energy security which OEUK thinks is critical.

“It’s important to consider where the bulk of global oil reserves are located. The IEA also states that it’s important to take workers along/ include and involve them on the net zero journey.

“To ensure that is the case, OEUK states that it is important to continue to invest in our own UK resources to enable the delivery of a long-term orderly and managed energy transition and also to ensure there is resilience and stability in the oil market that we continue to heavily rely on.”

When asked about if it takes into account oil demand from domestic products when reporting, IEA told Energy Voice: “We do indeed take this into account.”

The group added: “There will be more on this topic in an upcoming report titled Oil and Gas In Net Zero Transitions that we will publish in late November.”

The UK’s non-energy oil demands

Many countries are still reliant on oil out with energy demand and firms such as Lego have recently encountered problems in moving away from petroleum-based products.

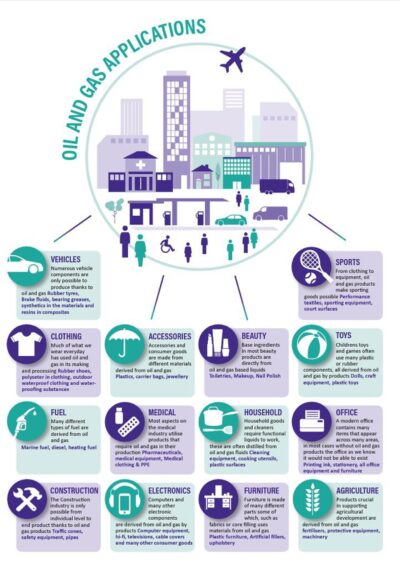

Offshore Energies UK (OEUK) published a document entitled ‘Everyday products of oil and gas’ in which it outlined the items in UK homes that are derived from hydrocarbons.

The list was extensive, ranging from sporting goods to pharmaceuticals and medical equipment.

The International Association of Oil and Gas Producers (IOGP) produced an infographic in 2020 to outline the products used by medical professionals that are derived from oil.

The list of products outlined by the IOGP included soap, masks, hand sanitiser, syringes, IVs, safety goggles, test tubes, artificial limbs and more.

The NSTA’s chief executive, Stuart Payne, highlighted the balance of imports in the UK. In June, he said: “Some of it goes through refineries as Product A and we then have to buy it back as product B – yeah, those things move around because that’s a reality of how that world works.

“We still need to do the work around making sure we have control over those molecules. It’s still a security of supply issue, it’s just a different one.”

Mr Payne’s comments are reflected by the documents produced by IOGP and OEUK that show how big of a role oil plays in the everyday lives of people in the UK.

Travel and its reliance on oil

Household products are not the only source of oil demand in the UK, as OEUK point out fuels such as diesel also require fossil fuels.

OEUK’s Ross Dornan said: “The vast majority of UK oil use is in transport – (over 70%). This is the key part of reducing enduring oil demand.

“So alternative fuels like hydrogen have an important role, especially in heavy goods transport and electrification is crucial for cars.

“It’s important to invest in the scale-up of the infrastructure required for this to incentivise change to alternatives to combustion engines.

“The UK government did have a 2030 date for all new car sales to be zero emissions, but have pushed this back to 2035.”

Recently, UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak rolled back the deadline for the sale of new petrol and diesel cars.

Sunak’s rolling back of green policy, which pushed back the ban back to 2035, prompted outrage in the energy sector.

Businesses described the call as a “historic mistake” at the time of the announcement.

Following DNV’s recent Energy Transition Outlook report, the firm’s group research programme director and the document’s co-author, Sverre Alvik, said: “Global emissions are still not peaking. We do see a record high installed of renewable energy.

“We saw last year that the solar wind batteries are performing well.

“That does not really help for the global emissions because no electric vehicle, no solar panel, is reducing emissions only if you retire the combustion engine vehicle or if you retire the gas or the coal plant, then emissions will fall.”

‘Whatever can be electrified should be electrified’

Mr Alvik has explained that: “Whatever can be electrified should be electrified, or you could even say, whatever can be electrified will be electrified.”

However, there will be issues with electrifying long-haul transport vehicles, shipping and the aviation sector.

He said: “All passenger vehicles and all light and medium trucks are likely to be electric but for heaviest trucks and aviation… and for shipping, everything but short sea, you cannot electrify.”

To solve this issue and reduce the demand for oil and gas in these industries, the DNV group research programme director forecasts the need for hydrogen and e-fuels to take the place of hydrocarbons.

“There will likely be biofuel, especially in aviation,” he said, later adding: “While in shipping, they’re now investigating all sorts of solutions, including ammonia, methanol, advanced biofuels, even onboard capture, carbon capture and nuclear is being investigated and DNV’s forecast is that we will see a lot of lower or zero carbon Hydrogen based fuels and biofuels dominating overtime.”

The Energy Transition Outlook report co-author said that the role out of this technology will start in shipping and then ” in 2050 and beyond” aviation will also adopt lower carbon fuel sources.

UK oil imports

In 2022 the UK paid out more than more than £100 billion on annual energy imports, this is more than double 2021’s £117bn bill of £54bn, according to data, OEUK has reported.

Overall the country coughed up £117bn in energy imports with Ross Dornan saying at the time of the report: “About three quarters of the UK’s total energy comes from oil and gas – a proportion that has stayed constant for many years.”

In 2022, the UK spent about £63bn on crude oil, petrol, diesel, and other oil-based fuels, with another £49bn going on gas.

UK Government’s Office for National Statistics (ONS) data shows that energy imports from Norway alone went from £13bn in 2019 to £41bn in 2022.

In a conversation with Energy Voice earlier this Year Stuart Payne explained, in every scenario through to 2050, the UK will remain a net importer of oil and gas, so demand will continue to outstrip domestic supply for decades.

So the UK will be reliant on other countries for oil and gas, but it’s a question of to what extent.

Norway is cleaner, and remains the biggest exporter to the UK – but industry professionals have highlighted that LNG from the United States, with a higher carbon footprint, is the most likely source of extra supply for the UK.

The NSTA says cuts in flaring emissions over the last two years is the equivalent combined emissions of the cities of Aberdeen and Dundee. That’s a “lever of control” it can’t exercise over imports, Payne said.

The regulator is currently assessing 115 bids from the 33rd offshore round, which opened in January.

Recommended for you

© Supplied by Roddie Reid/ DCT

© Supplied by Roddie Reid/ DCT © Supplied by OEUK

© Supplied by OEUK © Supplied by IOGP

© Supplied by IOGP © Shutterstock / buffaloboy

© Shutterstock / buffaloboy © Supplied by DNV

© Supplied by DNV © Supplied by Michal Wachucik/Aber

© Supplied by Michal Wachucik/Aber