Saudi Arabia’s reversal of plans to bolster its oil production capacity has raised questions about the future of demand, but it points to another long-running risk to the kingdom’s energy petroleum revenue — rival suppliers.

State-run Saudi Aramco surprised the oil industry on Tuesday by announcing it won’t proceed with plans to bolster production capacity by about 8% to 13 million barrels a day by 2027.

The lack of an explanation for the shift from the company has invited a flood of speculation, notably whether Riyadh has grown more pessimistic about oil consumption as the world shifts toward low-carbon energy. Forecasters such as the International Energy Agency see demand for oil hitting a limit in the next few years.

Yet that’s only part of the equation.

Competing producers are another consideration for the Saudis and their OPEC+ allies, especially their nemesis for much of the past decade — US shale. A wave of rival supply means Riyadh is already keeping about 25% of its total capacity offline as part of an OPEC+ agreement, capping its output at a two-year low of 9 million barrels a day since July.

“Riyadh sees softer balances in the next few years, mainly on supply outside OPEC+,” said Bob McNally, president of consultants Rapidan Energy Group and a former White House official. For this reason, he believes the Saudis are “delaying upstream expansion plans instead of shelving them permanently.”

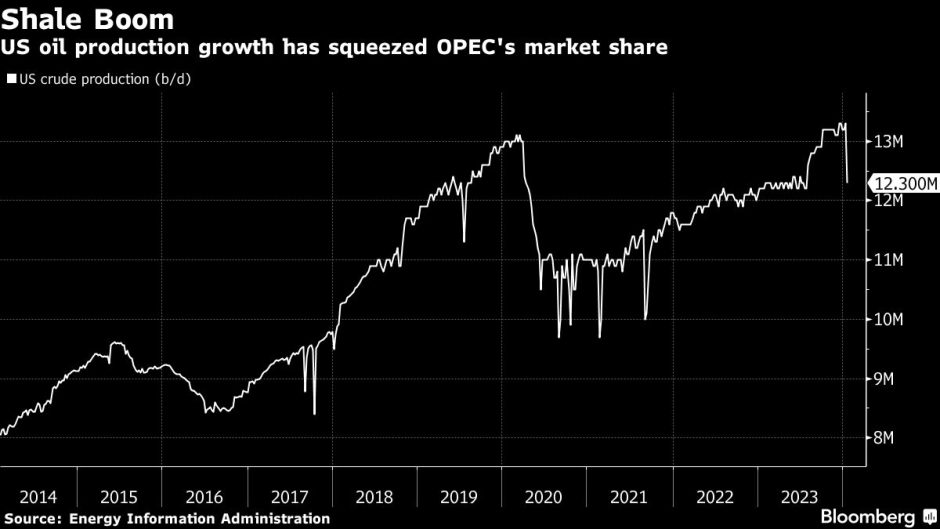

The US shale oil revolution unleashed a flood of new supplies onto world markets and sent crude prices crashing around a decade ago. In 2016, it had become an near-existential threat to producers that compelled the Saudis and Russia to overcome years of rivalry and form the alliance known as OPEC+.

Shale drillers retreated sharply when the Covid-19 pandemic erupted amid a collapse in world oil demand, and greater insistence from their shareholders for better returns meant it production was slow to rebound.

But in recent years they’ve staged yet another comeback, propelling American output into record-breaking territory above 13 million barrels a day. The deluge is being amplified by other producers too, such as Brazil and the emerging oil play of Guyana.

Amid this wave of new supply, oil prices ultimately sank 10% last year in London despite initial expectations of a rally as China’s economy reopened. The market has tipped from scarcity to plenty and Brent crude has largely remained near $80 a barrel this year even as conflict rages in the Middle East.

“There was an expectation in the industry that oil production in non-OPEC countries would come under pressure,” said Martijn Rats, global oil strategist at Morgan Stanley. But it has instead grown enough to satisfy demand, and “when that happened, the room in the oil market for OPEC oil came under pressure.”

If supplies from outside the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries can match consumption growth, then Aramco has less need to bolster its capabilities. Saudi Arabia has already prolonged its production cuts into the first quarter and Energy Minister Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman has said they can “absolutely” be extended.

“Today’s announcement reflects government expectations that demand for its oil will no longer rise as strongly as previously expected,” said Rats. “In that context, the current level of spare capacity is already sufficient.”

In addition to the trends on global oil markets, there are also domestic pressures behind Riyadh’s decision.

Saudi Arabia will probably post a budget shortfall of about 4.3% of gross domestic product in 2024 and have more than $46 billion of funding requirements, according to Dubai-based bank Emirates NBD. That comes as the kingdom continues to spend tens of billions of dollars on tourism, sports and other projects championed by Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman to diversify the economy.

Aramco is paying much more in dividends to the government, even with its production being cut. The company — 98% state owned — raised its quarterly payout by more than $10 billion to $29.4 billion over the previous two quarters as the government looks to fund its fiscal deficit.

Abandoning the 13 million barrel-a-day expansion should ease the pressure on Aramco’s budget by trimming about $5 billion a year from annual spending, according to RBC Capital Markets.

Recommended for you