It was in November 2011 that Reach CSG of Aberdeen submitted a planning application to drill a 1,000m borehole on the grounds of Devro in Moodiesburn, North Lanarkshire, then case to a depth of 100m and monitor the yield over a two-year period.

That application was turned down. However, the company is hopeful of being able to spud the first borehole near Shotts instead.

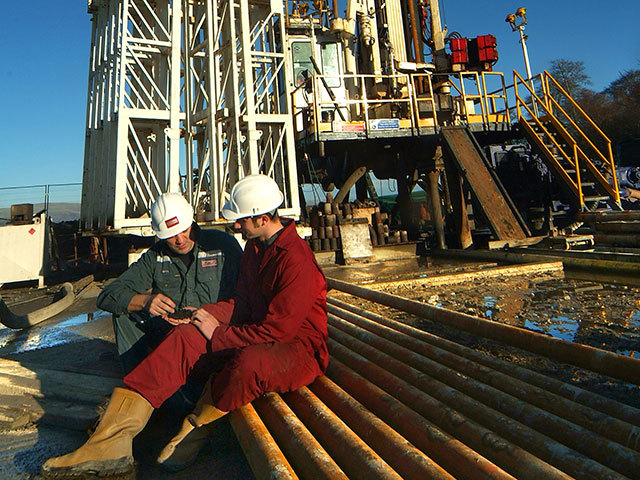

When drilling operations begin – this summer, it is hoped – it will mark a major step forward for the company, whose MD is Graham Dean, who is heritage Schlumberger, Amerada Hess and Centrica.

Reach CSG, which was formed in 2008, holds 400sq.km licence 162, which was awarded in the UK 13th onshore licensing round. This is the core of the company, which derived of Reach Oil & Gas, itself sold to Trapoil for about £30million in July 2011.

The group then held mostly carried interests in 14 exploration licences across 24 blocks and part blocks on the UK Continental Shelf. This included an interest in the Lybster field near Caithness, Scotland’s only producing onshore oil asset.

“All that we have is this licence in the Central Belt, which is very prospective for shale gas and coal seam gas, but the main interest is shale gas,” said Dean.

“We’ve mapped the estimate volume of shale gas that’s there; we plan to drill a borehole this summer… that’ll be for CSG and not shale gas. But we’re hesitating a bit because the Scottish Government needs to be openly and unambiguously supportive.”

This support is important as the company has already caught the eye of the anti-onshore production brigade that is also making life hell for Dart Energy, another company with a keen focus on the central belt.

It’s not as if hydrocarbons production is new to the region; not when one considers the coal industry, plus the shale oil sector that lasted for a century before petering out in the early 1960s.

“There were wells drilled as far back as 1919 in the region, including production from the Mid-Lothian oilfield (D’Arcy Oil) and the Causland gasfield,” said Dean. “I think Causland was still producing in 1965.

“There was also a well drilled in the city of Glasgow that flowed gas after fracking. It went on long-term production test for a while. That was in 1980.

“It was at the junction of the M73 and M8; I’m old enough to have driven past several times but even I didn’t notice it; it made so little impact.

“It was producing 3million cu.ft per day which, in those days was quite respectable.”

Dean takes exception to the anti-fracking movement that has emerged in the UK based on little data and the experience of one well drilled by Cuadrilla near Blackpool.

“There’s lots of hydraulic fracturing been going on in the North Sea. That’s one reason why Aberdeen is booming at the moment; with North Sea tight gas fields now being developed, such as Cygnus.”

But how large is the Lothian shale resource?

That is not yet known, though British Geological Survey is now working on that and due to report in the summer.

“There’s a lot down there; more than Scotland’s fair share . . . maybe 20% of what’s thought to be in the Bowland Shale. BGS’s estimate of that is absolutely enormous,” said Dean.

BGS’s Bowland median estimate is around 1,300trillion cu.ft of gas, though the upper estimate is almost twice that figure, 2,281tcf. This would make it by far the biggest shale basin in the world – apparently.

Even just 10% of the Bowland estimate would equal 130tcf, or about 50 years of total UK consumption.

It should not be forgotten that, where Reach plans to core, has been mined, as was so much of the central belt.

Some of the coal seams are inter-bedded with oil shales though, generally, the prospective shales are considered to lie beneath the coal seams.

Back to the Reach borehole programme; assuming success, the first Moodiesburn probe will likely be followed by two further boreholes.

“We’ll have to do another two in order to obtain the necessary samples, plus do other studies,” said Dean.

“Altogether this will cost £10.5million. Then we could spend about another £50million doing more wells, some of which would be fractured. Then we would go into the production phase where well depths would be in the range 1,000-3,000m.

“We’re a small company; there are six of us and we’re financed with our own money. The existing Reach licences were sold to finance things going forward.

“But shale (and CSG) gas creates jobs in places that need jobs. Everybody in Scotland knows someone who works in the North Sea. I want this repeated in the Central Belt.”