Ian Clark, who has died at the age of 85, wrote a book called Reservoir of Power, published in 1980. The cover depicted an oil rig at sea. Here surely, I thought, would lie the inside story of Shetland’s battle to control Big Oil. This did not prove to the case but demonstrated the complexity of this decisive figure in Shetland history.

The power to which the title referred was spiritual and the book was theological. Indeed, the only reference to his previous career came in the introduction where Clark wrote: “From an ordinary and rather obscure position I was catapulted into activities which were at the heart of oil developments in Scotland, and the result of my endeavours on behalf of the people of Shetland brought me professional success as well as a degree of notoriety.

“People have been kind enough to assume that the success flowed from some inherent personal ability. Whenever this point has been raised with me, I have been at pains to point out that this is not so, my success being dependent on the support which Jesus Christ gives to those who have faith in him”.

Whatever the source of his inspiration, Ian Clark was the right man in the right place at the right time. Having arrived in Lerwick as Zetland County Treasurer, the coincidental timing of local government reorganisation saw him emerge as chief executive of Shetland Islands Council in its formative years, at precisely the point when North Sea oil was becoming a reality with Shetland in the front line.

As well as Divine guidance, Clark was fortunate to have around him some councillors who would have been outstanding in any setting. Clark was a Lanarkshire man transplanted into Shetland but shared with them the clear understanding that unless Shetland controlled oil, the oil industry would consume Shetland just as it had trampled over so many other fragile cultures and peripheral societies.

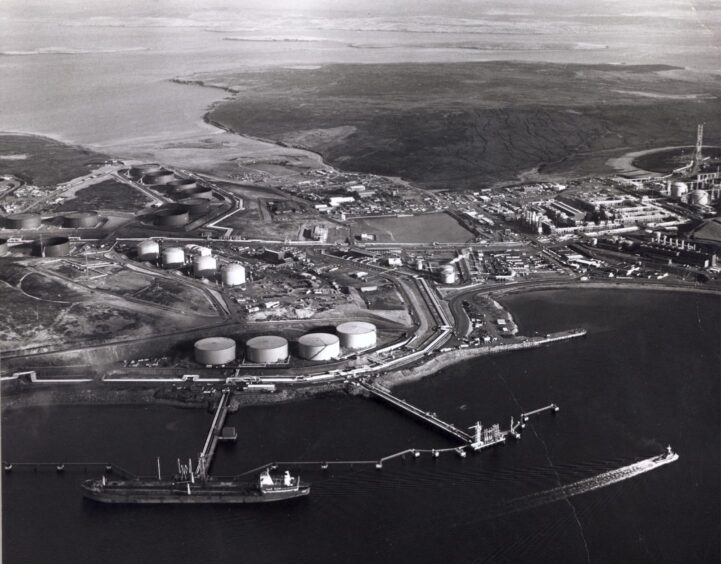

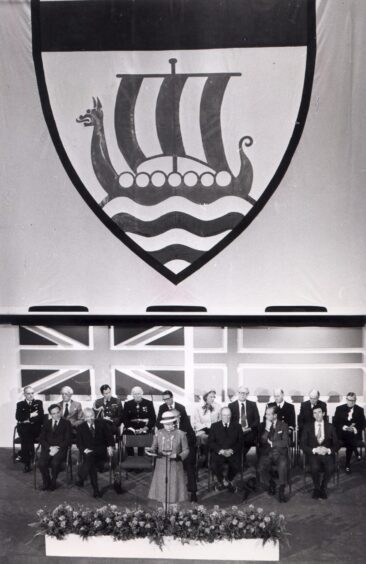

To prevent that course of events in Shetland, it was necessary to bring development under control. Equally, to ensure a legacy for the isles, it was critical to extract a levy from every barrel of oil that came ashore. The Act of Parliament which Shetland Islands Council promoted remains unique in the extent of powers it devolved to a humble local authority.

These included compulsory purchase of all relevant land and allowing the council to act as port authority and thereby concentrate oil coming ashore at a single, multi-user terminal at Sullom Voe. This brought Clark into direct conflict with oil companies and speculators, who were already buying up land at highly inflated prices.

In March 1973, the Ways and Means Committee of the House of Commons decided the Shetland Bill raised issues of such importance that it would have to go through a full Parliamentary process. This put it into the hands of Jo Grimond, the Orkney and Shetland Liberal MP.

Grimond opened the Second Reading debate by saying the Bill “may well point the way to better methods of controlling developments consequent upon oil discoveries in other parts of Britain” As far as Shetland was concerned, “the impact of oil on a rather unique island community will not go on for ever and may be over after 50 years … We must not sacrifice the long-term future of the community”.

The government of Edward Heath was desperate for the first oil to flow. While they did not like Clark’s approach or the precedent of revenues going direct to a local authority, they did not prevent the Bill from becoming law in the spring of 1974, thus clearing the way for Sullom Voe to be built.

Initially, Shell had seriously understated the Brent reserves and only as the truth emerged about the volumes of oil which would flow through Sullom Voe did the extent of Shetland’s ongoing financial benefits become apparent.

This is not just vital history which has become surprisingly shrouded in the relatively recent mists of time. It is also a parable for the present day. Once again, the north of Scotland is at the forefront of an energy revolution which has the clear potential to become a saga of exploitation and lost opportunities. For Big Oil, read Big Wind. But where is the leadership to play hard-ball on behalf communities? Where are the Ian Clarks?

When he left Shetland, Clark became a director of the British National Oil Corporation with the remit to develop its headquarters in Glasgow. By the late 1970s, BNOC was investing in the North Sea and around the world. Then BNOC was strangled in its infancy by Mrs Thatcher’s incoming government. Ian Clark remained joint managing director of Britoil until it too was sold off to BP; the last remnants of a state-owned energy company.

He retired to Campbeltown and pursued his interest in theology, securing a PhD from the University of Wales Trinity St Davids in 2010 to add to his Honorary LLD from Glasgow University and CBE. He died in Campbeltown on June 17th and is survived by his wife Jean, who he married in 1961, son David and daughter Susan.

By recalling the legacy of Ian Clark, we should be reminded of what is possible where political will exists and the yardsticks by which present and future policy can be judged when major energy interests clash with those of fragile communities.

© SYSTEM

© SYSTEM © SYSTEM

© SYSTEM