If there is one place where the price of natural gas will not be decided over the next decade, it is the UK. UK industry and consumers will instead be subject to the volatility of an international market, similar to oil, owing to the expansion of LNG trade and the UK’s gas deficit.

The comparison with oil has important exceptions. The international gas market does not have a body with the pricing power of the OPEC+ group, nor is one likely to emerge. The main producing countries – Australia, the US and Qatar – are open to free trade. Qatar renounced its membership of OPEC in 2019.

Nonetheless, under current market structures, the price of gas in the UK will be determined by the price of imports, and the price of electricity in winter, at least, will still largely be determined by the cost of generating power from gas – owing to the phasing out of coal and declining nuclear generation.

Gas deficit to persist

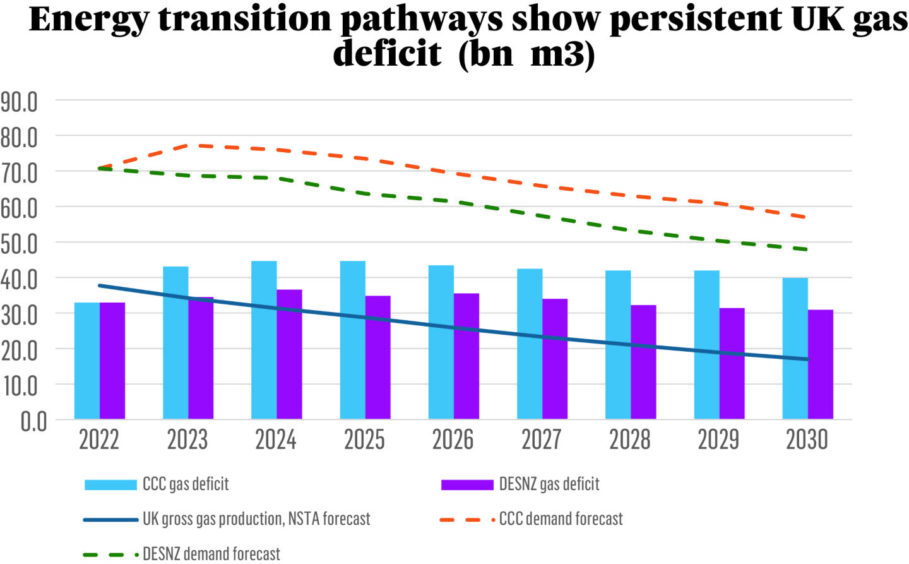

In 2023, despite a 10% drop in demand, the UK consumed 63.5bn m3 of natural gas and produced 34.5bn m3, leaving an import deficit of 29bn m3.

According to forecasts made by the North Sea Transition Authority (NTSA) in March, UK gross gas production will fall from 31.4bn m3 this year to 17.0bn m3 in 2030.

Demand projections vary based on the speed of the energy transition. By 2030, under the Committee on Climate Change’s Balanced Net Zero Pathway, demand in 2030 would be 56.9bn m3, and the import deficit 39.9bn m3. Under the Net Zero Delivery Pathway, published in April 2022, demand would fall to 47.9bn m3, and the import deficit would be 30.9bn m3.

Even though both forecasts over-estimated demand in 2023 (the CCC forecast by a lot), the key takeaway is that even with a speedy, on-target transition, the UK’s gas import dependency persists. Declines in demand achieved via energy transition policies are negated by falling domestic production.

Moreover, the balance of uncertainty suggests some energy transition targets will be missed (offshore wind for example), and there will be less domestic gas production than forecast in March, owing to an increased tax take and suspension of new licences negatively affecting the investment environment for UK oil and gas.

As such, the most-likely scenario is that the import deficit in 2030 will be similar to the current level, possibly higher.

Where will the price of gas be decided?

Back in the day – the day being pre-2015 – the UK’s National Balancing Point was Europe’s largest gas trading hub, but, since then, it has been eclipsed by the Netherlands Title Transfer Facility (TTF). The TTF gained even greater importance as Europe’s primary pricing point with the loss of the majority of Russian pipeline imports to Europe, following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in late February 2022, and Europe’s, particularly northern Europe’s, rapid expansion of LNG regasification capacity.

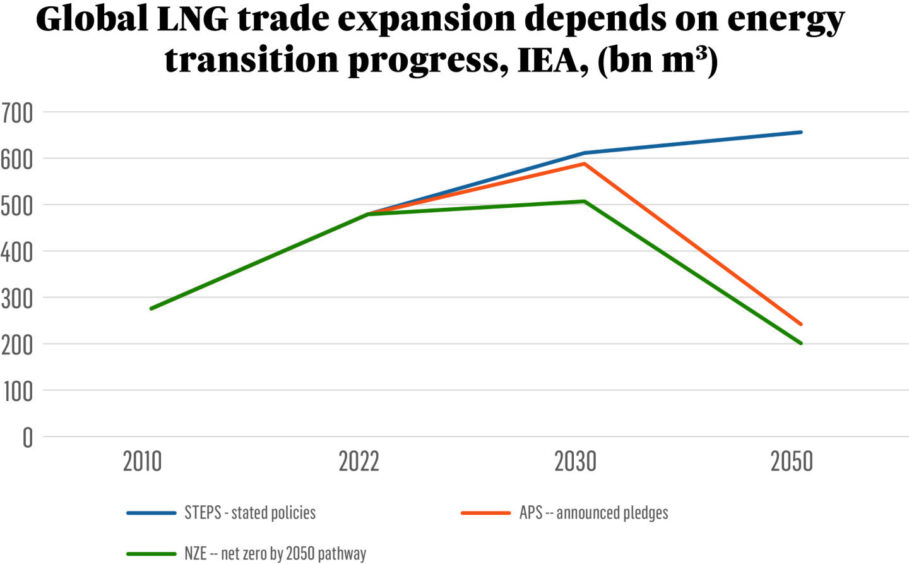

However, the locus of gas price formation has not simply moved across the Channel. From a group of disconnected regional markets, LNG trade has created a global market with Europe and Asia the two main demand centres, while the supply side is increasingly dominated by Qatar, Australia and the US. Price connectivity has followed.

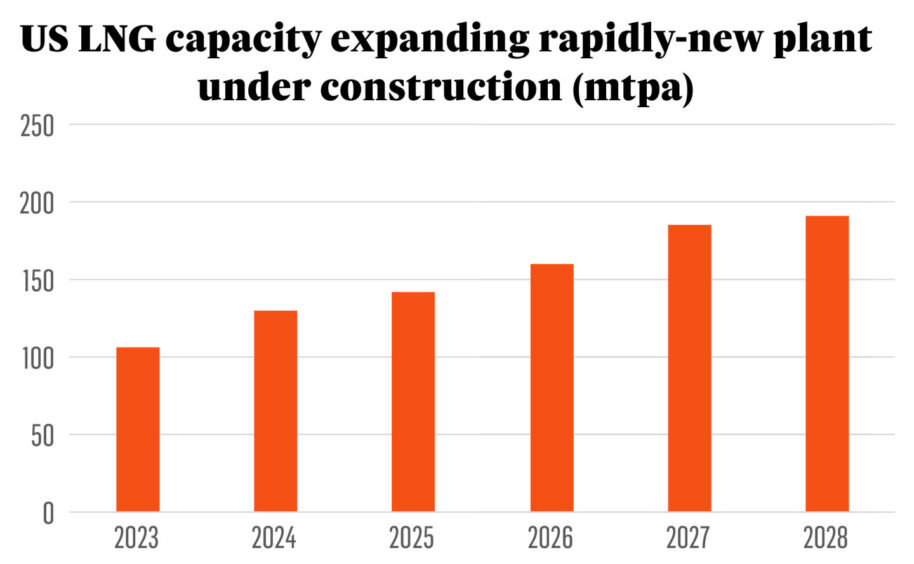

US domestic gas prices rose sharply in 2022 as in Europe, albeit to nowhere near the same extent. A number of factors lay behind the rise, but one was the increase in US LNG exports, which exceeded 100bn m3 for the first time. As US liquefaction capacity will rise by about 80% by 2028, developments in the US will increasingly affect the international LNG market and vice versa.

Meanwhile, the massive shift in Europe’s import slate from pipeline gas to LNG means it now vies with Asia for cargoes. The differential between spot LNG prices in Asia-Pacific and the TTF determines which market has the greater pull. Unlike pipeline gas, LNG cargoes can head to any regasification terminal, changing course if one location offers a better deal than another.

Europe’s winter gas balance

For UK gas prices, key determining factors in addition to the level of domestic consumption will be the gas balance in continental Europe and Asian LNG demand.

Europe appears to have weathered the gas crunch caused by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. However, mild winters have been a saving grace. Physical gas shortages were avoided, but consumers and industry have suffered the high price effects of scarce supplies.

At just over $13/MMBtu in late September, spot LNG prices are lower than last year, but still well above pre-invasion levels and winter is once again fast approaching.

The loss of Russian pipeline gas means northern Europe, including the UK, are dependent on a combination of domestic supply, storage, Norwegian gas and LNG. As the latter will provide the marginal molecule, LNG imports will set the market price.

There are negative factors which could make this winter difficult, and they are likely to persist. Gas traders are not using Ukraine’s large storage facilities because of the war risk. Kiev has said it will not renew its remaining contract for Russian gas coming to Europe via pipeline at the end of the year. And, the EU’s domestic gas production dropped 15.7% last year, the UK’s by 9.6% and Norway’s by 5.2%.

More positively, EU gas-in-storage is high – above 90% ahead of the winter, and renewable energy capacity continues to grow, but the deciding factor may once again be the weather.

The UK is particularly dependent on gas for heating and although it has a robust gas system in terms of pipelines and LNG regasification capacity, in-country storage capacity is still small relative to the size of the national market. If demand for both heating and gas-for-power rise in tandem, both the UK and continental European gas systems would be stretched – and additional LNG takes time to arrive.

Asia re-emerges as the engine of growth

Meanwhile, Asia has re-emerged as the dominant driver of LNG demand.

The continent consumes more than twice as much LNG as Europe and is split broadly between large traditional LNG markets – Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, Singapore, where demand is moderating – and growing markets China, India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Thailand and most recently Vietnam.

Of these, China is now the largest LNG importer in the world. Forecasts, both Chinese and external, suggest Chinese LNG demand will remain on an upward trend. Globally LNG demand is expected to rise by about 35% by the end of the decade, with growth dominated by Asia.

As Asia sucks in LNG supply from the Pacific Basin, more cargoes from the Middle East and Atlantic will head there providing price competition for European buyers. UK gas prices will be affected by the buying power of industry and consumers in south China and other Asian locations.

This does not mean that LNG prices, and thus UK gas prices, will necessarily be high. The growth of liquefaction capacity may outstrip demand, particularly in the period 2025-2028, when the majority of new under-construction US and Qatari liquefaction capacity is completed.

The UK might benefit from its growing exposure to an increasingly internationalised market for natural gas, but equally it may not. What is certain is that, while this exposure remains, the UK economy will suffer the effects of developments in distant lands through the price of imported gas in an increasingly connected global market. A speedy energy transition offers a solution, but it might be a rocky ride in the meantime.

Ross McCracken is a freelance energy analyst with more than 25 years experience, ranging from oil price assessment with S&P Global to coverage of the LNG market and the emergence of disruptive energy transition technologies.

Recommended for you