While US drilling on land has fallen along with the price of crude, the risky and expensive drive to pull oil from the depths of the Gulf of Mexico is showing little evidence of a slowdown.

Oil rigs working in the Gulf will increase by more than 30% this year compared with 2014, according to data from Wood Mackenzie, an industry consultant.

At the same time, the number of land-based rigs has fallen by a third since October, bearing the brunt of industry-wide cutbacks that have shed tens of thousands of jobs in the US.

The reasons are two-fold. The rise in deep-water drilling stems from years of planning and billions of dollars already invested, and the payoff can be considerable.

Anadarko Petroleum Corp.’s Lucius platform can handle as much as 80,000 barrels a day from the six wells that feed into it, an output that would take hundreds of onshore wells to reach, according to John Christiansen, a company spokesman.

“The economic life of these projects is in the decades,” said Fadel Gheit, an analyst for Oppenheimer & Co. in New York. “You’re going to milk this cow for another 30 years, so you don’t care what the price of milk is today.”

Large oil producers including Anadarko, BP Plc, Chevron Corp. and Royal Dutch Shell Plc are continuing to invest offshore even as shrinking profits force them to cut back on spending. BP has 10 rigs active in the Gulf of Mexico, which it says is a company record.

By contrast, in the oilfields of Texas, Colorado and North Dakota, producers are scrambling to rein in drilling as oversupplies have cut crude prices by more than half since June.

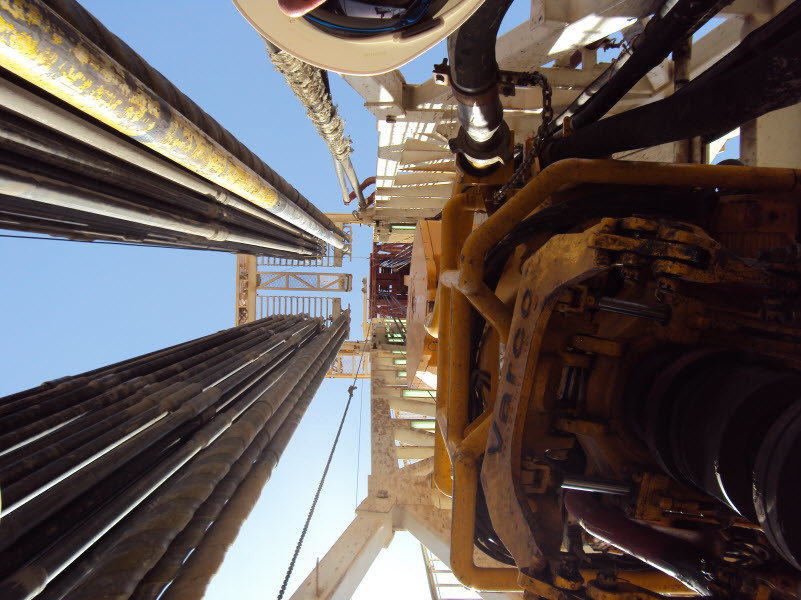

It’s a different calculus for prolific deep-water wells, which can produce far greater quantities of crude over a longer time span than a typical onshore well. The new wells are the latest step in a long-term development plan where much of the investment — in pipelines, platforms and subsea processing systems — already has been made.

“When you’re 90% complete, you’re not going to stop,” Gheit said.

Gulf of Mexico production will jump from 1.4 million barrels per day in 2014 to an average of 1.58 million barrels per day in 2016, a 13 percent increase, according to Wood Mackenzie projections.

The growth in deep-water will add to total US output, which is projected to grow by 14 percent over that period as rising efficiency continues to push shale production up despite declines in drilling.

Deepwater oil developments are so enormous they are referred to within the industry as “mega projects,” featuring platforms that can cost as much as $2 billion, wells that cost about $300 million to drill, and a system of pumps and processing equipment along the seafloor that can add another $100 million, Sandeen said.

“These aren’t onshore projects where you’re going to produce from a well for a few years,” said Jackson Sandeen, a senior research analyst covering the Gulf of Mexico for Wood Mackenzie.

“These are 30 to 40 year projects where a slight bump in the road in the short term is not really going to affect the project in the long term.”

The jump in rig activity in the deep Gulf of Mexico isn’t focused on exploration wells, where companies seek to confirm that oil prospects exist.

Oil giants are cashing in on previously confirmed discoveries by drilling wells into reservoirs that have already proven to be productive, and where they already have platforms built or under construction.

New projects, however, aren’t likely to get started unless oil prices rise to around $75 for a sustained period, said Brian Youngberg, an analyst for Edward Jones in St. Louis.

That’s leaving a fleet of brand new rigs entering the market with fewer prospects for contracts.

The rental rates for deep-water drilling rigs, which last year cost more than $500,000 a day to operate, have already fallen to $400,000 a day as fewer companies plan new projects, said Cinnamon Odell, senior rig analyst for industry consultants IHS Inc.

The costs of deep-water wells during a time of low oil prices is drawing some companies into partnerships to share costs as they push ahead on existing projects.

BP, Chevron and ConocoPhillips earlier this year said they would collaborate as they drill Gulf of Mexico wells in 24 jointly held offshore leases.

As part of the deal, BP sold Chevron half of its equity interests in the Gila and Tiber fields. The three companies also have joint ownership interests in exploration blocks east of Gila, known as Gibson, where they plan to drill in 2015.

By combining financial resources amid low crude prices, the companies are increasing the likelihood that they can find and develop new oil in the Gulf, which remains the most attractive offshore oil region in the world, Youngberg said.

Recommended for you