The world’s biggest oil and gas producers, already cutting hundreds of jobs a week from the UK’s North Sea, are just warming up.

BP Plc, Royal Dutch Shell Plc and Total SA are among those reducing staff, curbing investment or closing operations as oil prices that have fallen by half since June add to troubles from rising costs and aging resources.

About 1,500 jobs have been lost in offshore oil and gas this year, according to Unite, Britain’s largest labor union. Ian Wood, author of a state-commissioned report into the needs of the offshore fossil-fuel business, warned that about 15,000 positions relying on the industry could disappear in months.

“The 1,500 redundancies; that’s just the start,” John Taylor, Unite’s regional organizer, said by phone from Aberdeen, the Scottish city at the heart of the UK industry.

“Half of that is drilling. There’ll be more construction workers later as projects come to an end in the next two months.”

The early layoffs portend hard times for a whole ecosystem of explorers, drillers, producers and service companies, along with businesses that rely on the local demand they create.

About a quarter or a third of UK fields are uneconomic at current oil prices, BP Chief Executive Officer Bob Dudley said this month. His company announced 300 job cuts already this year.

“The main challenge for the North Sea is that fields that could produce for 10 to 15 more years will be shut-down earlier if the prices we are currently seeing persist,” Philipp Chladek, an analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence, said.

Investment will drop by more than half this year and 70% by 2018 on weak oil prices and high UK taxation, a lobby representing about 500 companies including the biggest energy companies said Tuesday in an annual survey of members.

The current rate of exploration drilling is the lowest since 1965, Oil & Gas UK said in its Activity Survey 2015.

Cash flows for North Sea operators were a negative 5.3 billion pounds ($8 billion) last year, the worst since the 1970s, as costs rose and revenues fell to a 16-year low, according to the report.

“I think 15,000 jobs will go in the next few months, before the end of summer,” Wood, who has been involved in oil and gas for at least four decades, said in an interview Tuesday.

“There will be significant negative impact on the economy of Aberdeen,” he said from the Scottish city. “It’s going to have a tough time as it depends on one industry, which is oil, and as the industry winds down in the medium term, in the next 20, 30, 40 years, it’s getting some taste of that.”

Companies looking to cut back include Total, which said February 12 it will reduce investment in mature North Sea fields.

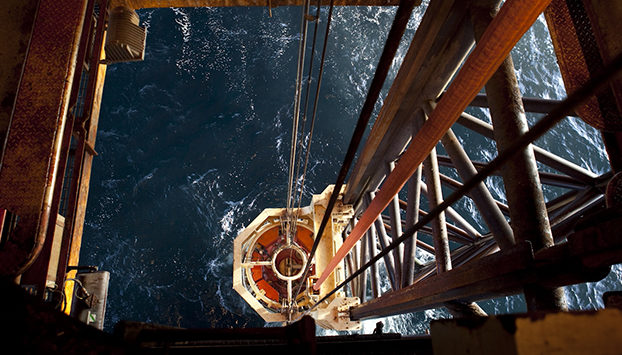

Shell, starting to exit the Brent oil and gas field after it exhausted reserves, will begin a consultation this month on plans to dismantle one of its four platforms in the area.

Talisman Energy Inc., Marathon Oil Corp. and Apache Corp. are also cutting back, according to Willie Wallace, Unite’s regional officer for offshore contractors.

Castlen Kennedy, a spokeswoman at Apache, said most areas affected by the 5% reduction in its global workforce announced in January are in the US Lee Warren, a spokeswoman at Marathon, also said the majority of its cuts were in America.

Press officials for Talisman-Sinopec in Aberdeen didn’t immediately return an e-mail and phone call seeking comment.

If there’s one thing that unites managers and unions, it’s that the Conservative-led coalition government needs to help.

Actual job losses, which are “extraordinarily difficult to estimate,” depend partly on the signal that the administration sends to companies it needs to invest in the region, Wood said.

Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne will make the case in his annual budget on March 18. He’s certain to bring in basin-wide field allowances to spur investment, lowering the tax take on the industry to just below 50 percent from 60 percent, according to Wood, who says he isn’t privy Treasury plans.

While that won’t satisfy the immediate demands of industry, unions or local politicians, it may mark a first step in helping prevent a stampede to the exit that would be hard to reverse.

“If you have the right tax environment, then I believe in the medium to long term there are excellent prospects still,” Fergus Ewing, Scottish government energy minister, said February 5.

Recommended for you