In May 2014, the new deal Gazprom signed to supply 38 billion cubic meters (bcm), which is about the amount NY state uses annually, of natural gas to China each year for the next 30 years changed the world more than anyone may have anticipated. It’s not just because it took 10 years to negotiate or was estimated to be worth about $400 billion at the time, but it seems to be the catalyst that sparked the current global oil war. In the midst of economic slowdowns in Europe and Asia and new technologies catapulting the U.S. into a leading world oil producer, OPEC decided to stop supporting oil prices and maintain market share by increasing oil production.

This isn’t the first time Russia has been at the receiving end of Saudi Arabia’s aim to maintain market share. Beginning in 1985, Saudi increased production by five times to drop the oil price from $32 to $10 a barrel, contributing to the collapse of the U.S.S.R. However, different forces are currently at work that are hindering OPEC’s strategy. While Saudi Arabia may be in a better financial position than Russia from their ability to produce oil cheaply, secure credit and continue investment, Russia – and the U.S. – have not slowed down production so fast. Russia’s economy has been helped by the ruble’s decline that has offset the U.S. dollar strength, and the U.S. producers have proved more resilient than Saudi might have expected.

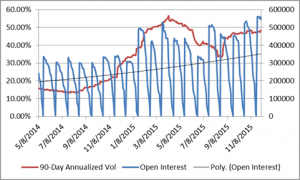

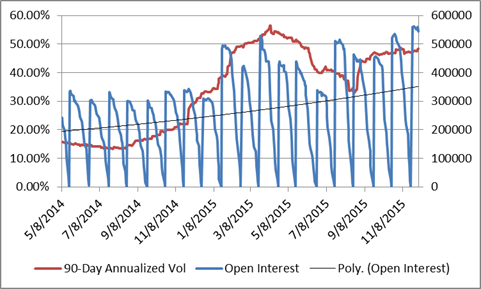

The industry is different now than in the past. Currently, the low oil price has forced consolidation where merged companies are improving efficiencies to bring down the cost of production. The race has changed from a race for land to a race for efficiency. New technology and operational responsiveness are reducing costs significantly for shale producers but they might still feel pain from low oil prices. The financing and investment may be more challenging going forward so that could slow production. There should be more clarity into how much production may retract after the producer hedges come due in the first quarter of 2016. The open interest in the futures market, one of the places producers hedge, may be a key factor to understanding where the oil market will stabilize.

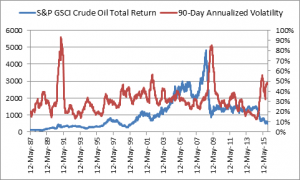

In the futures market, the price formation of oil is dependent on volatility as the market tries to stabilize. Please see the chart below for the historical relationship between oil volatility and price:

As OPEC continues to flood the market with oil, from a purely physical supply point (and all else equal,) oil price should fall, adding to the volatility. The higher volatility may become too much for investors that are long (opposite the short-side of hedging producers,) forcing them to sell. As the long side collapses, the futures market insurance becomes more expensive for producers. This may disincentivize producers to produce and store, forming the beginning of market stabilization. In the past, oil bottoms have coincided with peak volatility and a bust in open interest. Based on today’s levels, open interest of around 300,000 may be the level where enough production is halted to stabilize the market. This means there may be further increased volatility until more money exits the futures market. OPEC’s decision to continue production may accelerate this exodus. When open interest finally collapses, then oil may find its bottom. If the oil index matches its 2008-9 drawdown, history has shown prices may go as low as $28.

However, one indicator says oil may have reached the bottom or is very near. In historical oil bottoms, the energy equity risk premium, that measures the difference between the S&P 500 Energy Sector and the S&P 500 Energy Corporate Bond Index, has switched from a discount to a premium. This indicator switched in Oct. 2015 and held through Nov. When the stocks outperform the bonds, after a period of underperformance, it shows a switch in sentiment and has indicated the bottom of oil in the past.

After the last OPEC announcement, energy stocks took a big hit and the premium reversed into a discount again. This is bad news for the oil market, but what is worse is that China changed and may have more power than Saudi Arabia. Not only has China’s economic growth slowed, but they stockpiled oil on the cheap to fill their strategic petroleum reserves, so they might not need as much oil going forward. Moreover, after the stock market volatility and currency devaluation, oil got more expensive for China so they might not be the mega-consumer Saudi is racing to capture. It’s a bad equation when oil supply is not slowing and demand growth is not accelerating. That said, it’s possible the demand estimates are wrong since they are notoriously hard to predict.

Jodie M. Gunzberg is global head of commodities at S&P Dow Jones Indices.

Recommended for you