Efora Energy sees its future as balanced between the exploration assets, where it began, and the fuel supply side, where it has focused in recent times.

“In Africa, investors understand integrated oil companies in a way they don’t in the UK. The only oil companies listed in South Africa are integrated so that story resonates with local investors,” Efora’s CEO Damain Matroos told Energy Voice in Johannesburg. “In South Africa, focus is on exposure across the value chain.”

The fact that there is less infrastructure available in most African states means that those working in the upstream often have to invest in the midstream and even downstream in order to exploit resources.

Matching downstream work with upstream provides a “natural hedge”, Matroos said. Should oil prices go down, it makes the downstream business more robust, and vice versa.

The South African-based company has a range of assets around the continent. It has mature oil production in Egypt, exploration in Congo Kinshasa, an oil-lifting contract in Nigeria and downstream operations in South Africa and Zimbabwe. Efora was previously called SacOil Holdings.

Efora had brought Total into exploration in the east of Congo Kinshasa, taking the proceeds from this to Nigeria in order to seek some near-term production. The French company got the title of operator in the Congolese block and was carrying Efora in terms of the farm-in agreement.

“It’s a difficult place to effectively undertake the exploration activities in the Congo, as it is a jungle on the border with Uganda. The exploration activities were impacted by issues around security and the unfortunate infection in the region related to Ebola and these have an impact on executing plans,” Matroos said. The group shot 2D seismic on the northern part of the block, although less than planned which excluded the Virunga National Park.

Results from the seismic appeared to reveal a promising prospect, the executive said, but Total then opted to drop out. The remaining partners on the block have secured an extension for the exploration permit and are in the process of renewing the licence, which involves talks on the fiscal terms.

“If you look at the nature of the asset, the complexity, the capital requirements, it’s a significant opportunity. But it also requires significant capital and human resources. Firstly, our focus is to get our renewal,” Matroos said. The existing licence runs until July 2020.

Once Total had come into the Congolese blocks, SacOil had the opportunity to consider some additional options and ended up buying into OPL 233 and 281. This was more complicated than expected, and Efora is still working on extricating itself from exploration in the West African state, which has largely been achieved on the exit from OPL233 and in litigation on the OPL 281 to recover its capital.

A legal dispute on OPL 281 continues to rumble onwards.

Efora’s entry into Nigeria came through a decision to team up with Energy Equity Resources (EER). While progress on the upstream was disappointing, the two companies did manage to secure an offtaking agreement with Nigerian National Petroleum Corp. (NNPC), which was changing the way in which it was selling oil.

“In the first year, we secured four cargoes. Two cargoes in the second year and two cargoes in the next two years,” Matroos said. “The contract is coming to an end now. With our partner we will look at applying to renew that contract. It’s one of those things that you can’t do on your own, you need the local partner.”

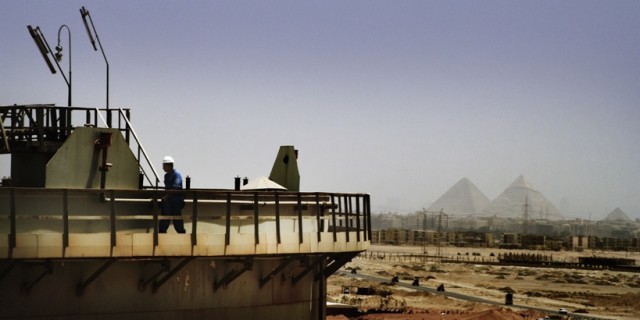

Following the Nigeria move, Efora bought the upstream Lagia asset in Egypt. This was an extension of the drive for additional streams of revenue to balance out exploration. “Exploration assets have a long lead time and to maintain that, with no income, creates a cashflow issue for a company, because you constantly have to look for funding to meet the ongoing running costs of the business,” Matroos said.

Oil produced from the Lagia field is heavy and priced at a 25% discount to Brent. Buying this production was a first step for the company in moving along the value chain, while retaining its focus on Africa, the CEO said.

Matroos compared Lagia to shale developments, with high decline rates and a need to continue drilling more wells. The field may require 80 to 100 wells. The company has drilled 10 wells thus far, with the 40 barrels per day of oil produced also carrying a high water cut.

Efora has sought to bring in a new partner at the field but as oil prices have declined the economics look more challenging. For now, the company intends to keep the asset on its books “and see what we can gain from producing”.

Downstream

The decision to buy into South Africa’s downstream market continued Efora’s policy of seeking exposure to the entire value chain in 2017 with the purchase of a major stake in Afric Oil. There are different capital profiles for the different parts of the business.

“The downstream business, Afric Oil, is more wholesale and logistics. Once you put an extra vehicle in the business, that doesn’t decline, you build up more capacity. Whereas with the upstream asset, once you’ve drilled a few wells they come up and then start declining over time,” Matroos said.

Efora’s downstream operations include involvement in Zimbabwe, although this has ground to a halt on difficulties extracting cash from the country. Initially, the pricing was good and the currency risk – when Zimbabwe was using US dollars – was minimised.

“Now, if I can’t get the money out of Zimbabwe, my South African business must pay to cover the supplies and you don’t know when you’re going to get the money [from Zimbabwe],” Matroos said, noting big corporates had the same problems. So, for now, work is paused. Efora has a supply facility able to supply transport and wholesale on the border, which is rented out to third parties.

Progress on the currency issue is the key area preventing Efora from returning to Zimbabwe, for now. Progress on this issue is unlikely to be quick, with currency devaluation putting pressure on the country’s citizens. “Extremely painful decisions need to be made and whether there’s significant political will to do so, is the challenge.”

At Efora’s South African business, the company has faced competition from illegal imports and illegal supply, blaming this for eating into demand for its supplies. “Those guys could bring it in cheaper than what you can buy from local refineries,” Matroos said, although increased border controls have tackled part of this problem of trading in illicit products.

Recommended for you